Rev. Nelson and abolition come to Quincy

The bluestem grass that grew tall enough along the Mississippi River to hide a man on horseback was all that stood between the Rev. Dr. David Nelson and a band of red-sashed pro-slavers looking for him on Sunday, May 22, 1836.

Public opinion for five years had been seething against Nelson, the founder and president of Marion College at Palmyra, Mo. The college had become the altar of abolition in the slave state. Its leader was an agent of the American Anti-Slavery Society for Missouri and one of the society’s vice presidents.

Nelson didn’t make it easy for his neighboring Missourians to get along with him. He had branded as sinners all associated with slavery — even anyone who failed to speak out against it. He warned that the consequence of failing to reject slavery was certain and eternal damnation.

The people of Palmyra were well aware of Nelson’s connections to abolitionism and uneasily tolerated them. By that May in 1836, Nelson had reached the conclusion that toleration was over. Even his own college faculty had turned against him.

“The faculty ... utterly condemn any interference with rights guaranteed by the

State of Missouri to the owners of slaves,” they said.

With few friends and many armed enemies, Nelson had decided to move to Quincy.

David Nelson had become a trained medical doctor by the time he was 19, volunteered as a surgeon in a Kentucky regiment during the War of 1812 and was with Gen. Andrew Jackson in his invasion of Florida in 1818. Jaded by what he saw in war and influenced by his reading of Volney, Voltaire and Paine— deists who believed man’s morality was informed by his needs — Nelson shed his religion.

After military service he returned home to Jonesboro, Tenn., and established a medical practice that generated income of $3,000 a year. In time the money proved to be unsatisfying. So did his religious infidelity.

Said a biographer, “The wonderful processes of his mind (gave) up this infidelity by reluctantly detecting the dishonesty and unfairness of Voltaire and other infidel writers and by a patient, intelligent examination of the whole subject of his own heart ... and especially in the word of God. ...”

Nelson at the age of 25 joined the Jonesboro Presbyterian Church, “deploring his long rejection of the Saviour he now delighted to honor, and resolving to redeem the time by the unreserved consecration of all his powers to Him.” He attended Centre College at Danville, Ky., preached there and worked to start the Danville Theological Seminary. At college he developed an anti-slavery spirit, freed his slaves and sent them to Liberia. His notion of abolition favored the colonization of free and freed blacks outside the United States.

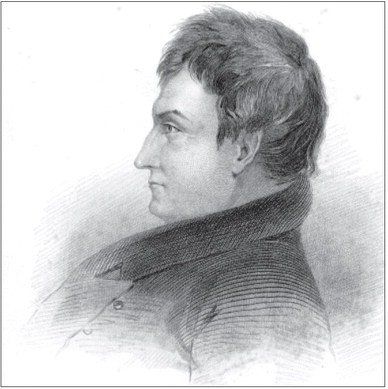

In the pulpit, the Rev. Nelson at six feet tall and 250 pounds was imposing. As a preacher whose emotion during a sermon could move him to tears, he was said to have few equals in eloquence and effusion in the spirit of Christ. In January 1832, he preached in St. Louis’s First Presbyterian church to hundreds of men and women who felt his “surgeon’s knife probe deeply” into their conviction to sin.

Among the attendees was a spiritless Elijah Parish Lovejoy, who had resisted Nelson’s “knife” but found himself converted by the end of the two weeks of revival. Lovejoy’s conversion was so complete that he became a Presbyterian minister determined to end the sin of slavery. His firebrand anti-slavery newspaper, the Alton Observer, cost him diminishing support in Alton, and friends in Quincy repeatedly urged him to move his press there. Lovejoy declined and in November 1837 he was martyred by a pro-slavery mob in Alton.

Nelson sought to multiply the spirit that had moved infidels like him and Lovejoy. It was this spirit, he was to say, that “led him to lay the foundation of Marion College in Missouri.”

Initially, he chose to establish his college at Green’s Landing on the Mississippi, renamed Marion City, which was a few miles north of Palmyra.

Col. William Muldrow had invested huge sums in land there and developed lots. His plan was to build a rail terminus to the Pacific to make Marion City the commercial center—replacing Quincy—on the Upper Mississippi. The plan lured to Marion County money and easterners, who brought with them their unpopular ideas about slavery. The river intervened. In 1835 it flooded over Marion City and dissolved Muldrow’s plan.

It was Muldrow who ran Nelson afoul of his neighbors that Sunday in May of 1836. Against his own better judgment, Nelson consented after a camp meeting that day to read an appeal by Col. Muldrow, a college founder and now a board member, for contributions to colonize free blacks in Africa.

For several listeners, the request represented the final insult against their slave institution. It demonstrated to them that Marion County had become “... a selected theatre of action for the dissemination of the principles, and the accomplishment of the objectives, which form the band of union of antislavery associations of the east.”

Many owned slaves, albeit small numbers of slaves, in Marion County. Fighting — some called it rioting — erupted, and Dr. John Bosley, a slave owner who had stirred it, was stabbed.

Nelson was blamed for the altercation and his frantic wife persuaded him to flee to Quincy. For the next three days he sneaked wet and muddied along the river bank, sinking to his stomach when even the wind masqueraded as a marauder moved through the grass.

On the third day Quincy abolitionists John Burns and George Westgate found Nelson, who by then had traversed the bottoms of the South Fabius River to a point across from Quincy. Nelson’s rescuers had brought dried codfish and crackers for him to eat. It was unusual but welcome food for the fugitive, whose palate favored fat in his fare. He told his deliverers they would make a Yankee of him and that he “may as well begin on crackers and codfish.”

Nelson spent the night in Rufus Brown’s Log Cabin Hotel, site of today’s vacant Newcomb Hotel on the southeast side of Fourth and Maine streets. Fresh sheets and a feather pillow made the rest pleasant. But it was disturbed early the next morning by several Quincyans who wanted Nelson given up. Word had circulated earlier that Nelson had stabbed Dr. Bosley. When it became clear that Nelson planned to move his family and his troublesome college to Quincy, the “self-constituted committee of citizens” demanded he return to Missouri.

“The men of this committee ... were not bad men, but simply Democrats,” wrote Henry Asbury, a lawyer and local historian, about the altercation.

Democrats or not, John Wood, Quincy founder and leader, brought 30 armed men to confront the mob at Brown’s hotel. If they were going to take Nelson, Wood warned, “they would have to take him over their dead bodies.” Wood’s determination broke up the crowd. It was the first time since 1823, when he fought a pro-slavery legislature’s attempt to make Illinois a slave state, that Wood once again put his own sensibilities about slavery on the record.

Two weeks after Nelson’s arrival, a notice was placed in the Illinois Bounty Land Register, Quincy’s first newspaper, “for a ‘county meeting’ in the public square, on the 18th of June, of all citizens of Adams County friendly to peace and good order, and opposed to the introduction of Abolition Societies and opposed to the discussion of the subject in the pulpit.”

The struggle over slavery had crossed the river.

Reg Ankrom is executive director of the Historical Society. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.