St. Louis World’s Fair Changed Foods in Quincy

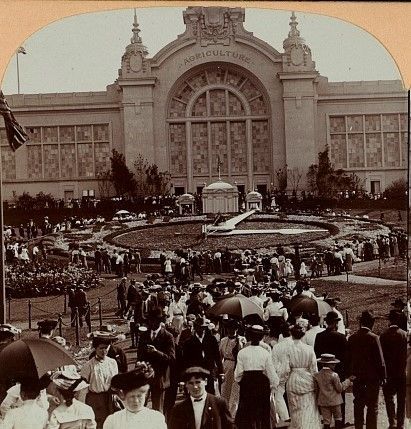

The Agricultural Pavilion at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair showcased scores of new foods, cooking methods, and nutritional standards that changed how Americans ate and prepared meals. Many foods popularized at the fair soon became part of the Quincy public’s eating habits and druggists sold others as medicines for fighting disease or supplements for improving health. (Photo courtesy of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County)

The Louisiana Purchase Exposition, informally known as the St. Louis World’s Fair, began on April 30,1904, and drew nearly 20 million worldwide visitors during its seven-month run; it remains history’s largest world’s fair. During the years following its close, this exposition changed many aspects of life, including how Americans prepared and ate food.

The Agricultural Pavilion was the fair’s largest and most popular attraction, featuring new foods, cooking methods, and “modern” dietary standards. The fair celebrated the burgeoning century’s belief in progress based on science and medical research into public awareness. Perhaps the most significant changes occurred with greater food safety and healthful eating habits.

Women in the local Civic Improvement League began clamoring for a modern board of health and a Quincy Health Department to combat food-borne illnesses and diseases related to diet. Some league members even asked the city council to raise the daily food allowance for jailed inmates from 25 cents to 50 cents (equivalent in today’s dollars from $4.20 to $8.40), provide safe drinking water, and include monthly fresh fruit. These measures, they argued, would curtail the spread of communicable diseases stemming from meager “sickly” diets.

Many foods and drinks that had only limited regional appeal became popularized at the fair and are advertised now for their health benefits. After long domination by local German-descended brewers, William Hasse in 1906 introduced at his 215 Oak Street store in Quincy a new brand into the beer market here: Schlitz. He promoted it as “Pure and natural health insurance. The beer that never makes men bilious.”

The fair displayed the new invention of refrigeration that chilled water. “Eating Houses,” as restaurants were called then, like the Hotel Quincy and Majestic Cafe, prominently listed chilled water on their menus along with iced tea. While people in Quincy had been drinking hot tea since the city’s founding (and for millennia around the world) this libation became so prized that Pinkleman-Barry Company sold seven brands of loose tea ready for steeping and icing. In a July 23, 1917, advertisement in the Quincy Daily Herald, the company stated: “Ice water is very bad for a person who is hot, while the same person can drink iced tea without any bad results, in fact iced tea is very wholesome.”

Quincy drug stores began selling some foods and beverages unveiled at the fair as medicines, including yellow mustard and Dr. Pepper. Owl Drug Store and Brown & Mays Druggists claimed in their ads that yellow mustard could cure sore throats and tonsillitis, and yogurt (a “wonder drug”) could overcome Bright’s Disease, eczema, colitis, appendicitis, gall stones, and a host of other maladies. Druggists also announced that Dr. Pepper remedied dyspepsia, diarrhea, and acid reflux; only much later did it and other medicinal products like Coca-Cola become known as “soft drinks.”

Peanut butter had long been used as a protein source for people unable to chew meat because of dental problems. Concession stands at the fair sold it as a food spread on bread for eating on the run. It became so sought after that Smith Peanut Butter factory at 416 South 8th Street in Quincy expanded its business and advertised to all citizens. The company also heralded the fair’s novel peanut butter and jelly sandwich as a delicacy for children and adults.

Today, some sources state that the St. Louis World’s Fair introduced the first ice cream cone. Like so many other products, the fair only popularized it and thrust it onto the national stage. Cones soon became so favored by the public that Sherman Rossiter formed a booking agency for Quincy stores wanting to sell them and George Speidle started an ice cream cone shop in the alley on Maine Street between 5th and 6th. Long before the cone’s ascent as a dessert, ice cream sandwiches had been a treat in Quincy and elsewhere.

One of the fair’s few original products, puffed rice, became a nationwide sensation and ushered in “fast food” breakfast cereals. To promote these products, J.E. Linehan, an official with the Egg-O-See Company, stated in an article for the January 29, 1909, Quincy Daily Whig: “The first time the Bible mentions breakfast, it compares the ordinary breakfast food product [of Biblical times] with ‘husks’ upon which the Prodigal Son fed while away from home.”

The fair displayed cuisines from around the world and soon interest in foods from cultures as diverse as Mexico and Asia spread across the country. The Young China Cafe opened at 514 Hampshire Street with Fred Toy as manager. People slowly overcame their reluctance to eat “foreign” foods, but not without resistance. Rumors begun at the fair that some nationalities used canines as meats created the derogatory term “hot dogs” for what people previously called wieners or sausages. Only much later did this new name become accepted and palatable.

Sarah Tyson Roer rose to celebrity status at the fair and across the nation for introducing new cooking methods and cookbooks. Mrs. Nancy Moeker of Quincy’s Pacific Hotel accepted a position at Roer’s Innside Inn and spent the summer of 1904 there before bringing innovative culinary ideas back to the Gem City. Cooking schools began at the local YWCA, Masonic Lodge, and the Quincy Daily Whig. Cookbooks for young housewives became valuable wedding presents guaranteed, some claimed, to save women “hundreds of hours in the kitchen.”

A quarter century after the St. Louis World’s Fair closed, the Great Depression began and for most people in Quincy and across the country health foods, sanitation measures, and new cuisines collapsed into an ongoing struggle to survive. Cooking schools, lavish dinner parties, and diets designed to improve well-being turned into soup kitchens and bread lines. Only after World War II ended in 1945 and a post-war prosperity emerged did the majority of Quincyans—as well as most Americans—once again see their meals as more than providing enough sustenance to live.

Sources

“Drink Iced Tea For Health.” Quincy Daily Herald, July 23, 1917, 5.

“Food For Spring Fever.” Quincy Daily Whig, Jan. 29, 1909, 2.

“Insurance of Health.” Quincy Daily Journal, Sept. 4, 1906, 2.

“Intestinal Autointoxication.” Quincy Daily Herald, Dec. 4, 1908, 3.

“More Food for Prisoners is Wittman’s Plea.” Quincy Daily Journal. May 28, 1918, 3.

Rowland, Francis David. ed. The Universal Exposition of 1904, Vol. 1. St. Louis, Mo.: Louisiana

Purchase Exposition Co., 1913, 184-188; 449-498.

Vaccaro, Pamela J. Beyond the Ice Cream Cone: The Whole Scoop on Food at the 1904 World’s

Fair. St. Louis, Mo.: Enid Press, 2004.