Stephen A. Douglas’s Family in Quincy

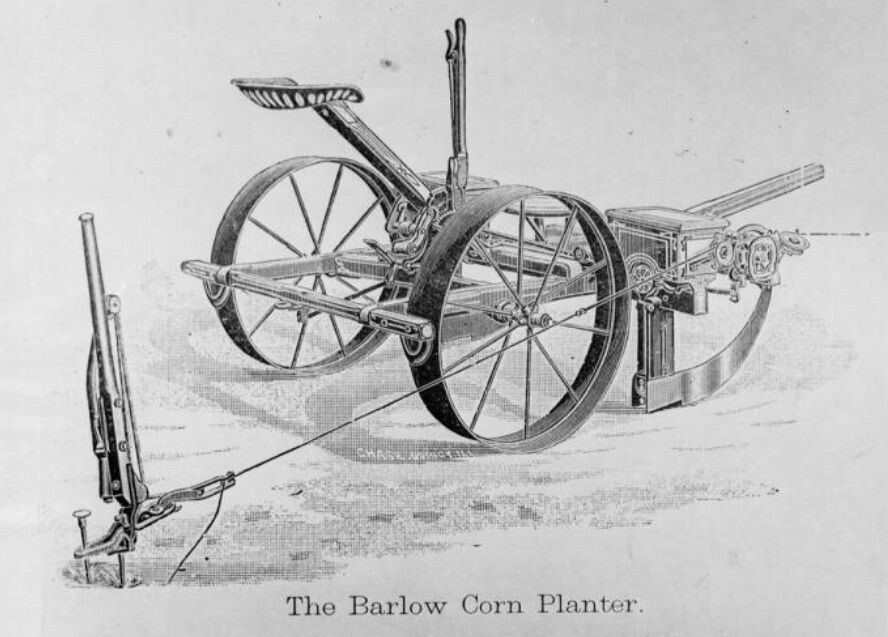

Barlow Corn Planter. (Courtesy Illinois Digital Images, Illinois Secretary of State)

The wife of Congressman Stephen A. Douglas may have been the only person in the extended Douglas family not to have considered it a strange irony that her husband’s achievements in Congress stopped her parents’ plan to move from North Carolina to Adams County. Martha Denny Martin, 22, and Douglas, 34, were married on April 27, 1847. Her older sister’s death on the eve of her own wedding meant Martha was the sole surviving child of Martin and Mary Settle Martin. And they lavished their affections on her. They so idolized her that they decided to sell of all of their holdings, including plantations and slaves, to be near her. By July 1847, her father wrote Martha that they were “determined to settle for life in the neighborhood of Quincy.”

Martin, however, soon postponed the sale of his properties. The admission of Florida and annexation of Texas into the Union in 1845 had sent land values plummeting. And the anticipated acquisition of 550,000 square miles of land after the Mexican American War would make a poor market for land even worse.Martin’s son-in-law Stephen A. Douglas was responsible for that. His efforts in 1845 engineered the admission of Florida and Texas into the Union. He also would pass the Compromise of 1850 to acquire the huge Mexican Cession.

Keeping their slave properties, the parents of Douglas’s wife did not move to Quincy. And Martha and Stephen A. Douglas did not stay. Martha Martin Douglas was never happy there. After Western Illinois voters in 1846 re-elected Douglas to the House of Representatives, the Illlinois General Assembly elected him to the U.S. Senate. His constituency now spread across the state, Douglas and his wife moved to Chicago in 1847.

In that same year, Douglas’s Aunt Honor, sister of Douglas’s father and physician Stephen A. Douglas Sr. of Brandon, Vermont, and her husband, Dr. Joseph King Barlow, moved to Quincy with their six surviving children. Five had died in childhood.

Barlow graduated from Vermont’s first medical college in Castleton, Vermont, and he and Dr. Douglas operated medical practices in neighboring Brandon and Barnard. The Barlows were so close to Dr. Douglas that they named their eldest child for him. Stephen Arnold Douglas Barlow was born in 1816. Dr. Douglas’s only son, also bore his father’s name. The junior Stephen A. Douglas was less than three months old when his father, 32, died of apoplexy, which today is called a cerebral hemorrhage or stroke, on July 1, 1813.

The Barlows were active in Quincy by the time the second wave of cholera struck the community in 1849. The disease killed Dr. Barlow on July 23, the day he visited a suffering patient at his farm east of Quincy. Cholera also killed his wife Honor Douglas Barlow on August 5 and son William R. on August 6. Their bodies were buried in Woodland Cemetery. The youngest of the five surviving children, Joseph Chouteau Barlow, 13, showed promise in business and industrial arts. By age 22 he was head bookkeeper and cashier for a large hardware company in St. Louis.

On February 25, 1858, Joseph Barlow and Eveline W. Streeter were married in the John Wood Mansion at 12th and State Streets. Eveline was the sister of Anne Streeter Wood, wife of Quincy founder John Wood.

After Joseph Barlow’s service in the Quartermaster Corps during the Civil War, Joseph and Eveline returned to Quincy. In 1865, he and Joshua Streeter Wood of the Quincy Wood family formed Barlow, Wood & Co. to manufacture corn planters. For Joshua Wood, it was an improvement in circumstance. John Wood, while quartermaster general of Illinois during the Civil War, asked one of President Lincoln’s personal secretaries to help advance his son. On John Wood & Sons Bank letterhead, dated October 7, 1862, he asked John Nicolay to expedite Joshua’s appointment as a government paymaster. Wood wrote that his son was “very unsettled” having not heard any result of his application. The Secretary of War, Wood wrote, was in favor of it.

“If you will interest yourself in his behalf to secure his commission without delay,” wrote Wood to Nicolay, “I will esteem it as an especial favor, the which I should ever be ready to reciprocate.” By the end of the war, Joshua Wood did not need a government job. He and Barlow teamed up to manufacture corn planters in a facility that took up a full city block at the foot of Cedar Street on Quincy Bay and employed one hundred people. Barlow’s innovations in the planter propelled farm productivity and farmers’ demand. Within the first three years, orders grew from 550 to more than 2,000.

Four years later, local newspapers in early January 1869 advertised that Barlow and Wood “by mutual consent” had dissolved their partnership on December 25, 1868. Neither the notice nor news story reported a reason.

Barlow, 58, died Thursday, June 6, 1895. He left his wife, four adult children, and a sister, Martha, wife of Quincy sculptor Cornelius Volk. Another Barlow, Joseph and Martha’s sister, Emma Clarissa, married Cornelius’s brother Leonard Volk. The Volk brothers met the Barlow sisters when Cornelius lived with the Dr. J.K. Barlow.

Stephen A. Douglas paid for Leonard Volk’s two-year study of art and sculpture in Italy. Leonard taught Cornelius the art of sculpting. Leonard named his first son for his patron, Stephen Arnold Douglas Volk, who became a heralded painter. The story of the Volk brothers continues next week in the third installment of the Douglas family.

Sources:

Ankrom, Re. Stephen A. Douglas, Western Man: The Early Years in Congress, 1844-1850. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing Co., 2021, 217-218.

“Cholera Epidemic of 1849 in Adams County,

https://adams.illlinoisgenweb.org//history/cholera.html

“Dissolution of Co-Partnership,” Quincy Daily Herald, January 5, 1869, 3.

Douglas, Charles H.J. A Collection of Family Records with Biographical Sketches and Other Memoranda of Various Families and Individuals Bearing the Name Douglas. Providence: E.L. Freeland & Co., 1879, 242.

John Wood to John Nicolay, October 7, 1862 Abraham Lincoln Papers: Series 2. General Correspondence. 1858-1864; Library of Congress, at

https://www.loc.gov/resource/mal.4236000/?sp=1&r=0.217,-0.093,1.369,0752,0

“Joseph Barlow Is Dead,” Quincy Whig, June 6, 1895, 3.

Lane, Francie. The Martin Family History, Vol. 4. Yuba City, CA: Martin, 2016, 243, 247, 249.

Wm. Barlow, “My Heritage,” at

www.myheritage.com/names/wm_barlow