Teacher sued steamboat for discrimination and won

Nineteen-year-old Emma Coger was a seventh-grade teacher at Quincy's segregated Lincoln school in 1872, when a September trip to Keokuk, Iowa, changed her young life dramatically.

She was visiting friends, and on the return trip home an incident aboard the steamboat S.S. Merrill took her all the way to the Iowa Supreme Court. The case tested her resolve and her willingness to stand up to vindicate the rights of her race.

She boarded at Keokuk and attempted to purchase a first-class breakfast ticket. The clerk wrote on it that she was to eat on the outer deck or in the pantry with the chambermaid.

He had noticed her slightly darker complexion, and honored the steamboat's tradition of denying first-class dining privileges to passengers of any African ancestry.

Coger said she was not a servant and would not eat in the pantry with the servants. The clerk replied that he couldn't sell her any other ticket and returned her money. Coger missed breakfast, but then gave the chambermaid a dollar to purchase a 75-cent dinner. The maid told the office the ticket was for a "colored" girl like herself, and returned with 50 cents and a second-class ticket.

The public school teacher had not previously been denied dining privileges on a Mississippi River steamboat, although her sister Zenobia had a similar experience on a trip to St. Louis with several white female friends from Quincy.

Coger's frustration would not allow her to dismiss this issue. She was stubborn about her Constitutional rights, and asked a white gentleman to buy her a first-class dinner ticket. He obliged and gave her 25 cents change from her dollar. Dinner was soon called.

The wife of the boat's captain, who was from Canton, Mo., knew Coger and became indignant about her sitting at their table. She rose, along with two other table members; although two other women remained seated and did not object to dining with Coger.

The clerk tried to pull her chair from under her and jerked away her ticket. Coger remained seated, and the clerk went for the captain. The captain arrived, and he forcibly removed her from the table, breaking dishes and spilling food. In the cabin he struck her on the head, and Coger testified that he said, "You negro; I will land the boat and put you off."

"I dare you to do it, sir," Coger retorted. Humiliated, hungry and angry, Coger stayed in the cabin and continued to Quincy. The newly built Lemen Brothers Warehouse (that is still used on Third Street between Hampshire and Maine) must have been a welcome site as she neared home. She lived on the same block with her mother, and had a story to tell.

Her rage was focused, and when she landed in Quincy she tried without success to find a local attorney to represent her. All declined to represent her, thinking she would lose the case.

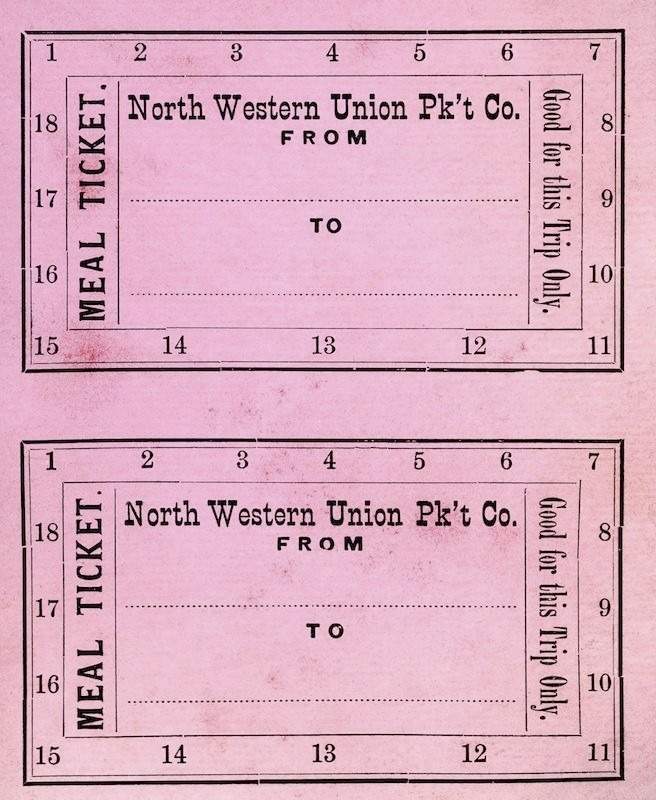

Disappointed, Coger almost gave up her idea to sue, until a neighbor suggested an older lawyer in Keokuk who might tackle her case. She hired the firm of McCrary, Miller and McCrary, and sued the North Western Union Packet Company in Iowa's district court in Lee County. Assault and battery were the official charges, although racial discrimination fueled the incident.

The trial began in February 1873, and the defense had many witnesses. The steamboat captain admitted to hitting Emma and knocking her hat off but said she first hit him. He and other witnesses accused her of using vile language and exclaiming that she "would make you pay for this."

Coger maintained her composure in the packed courtroom and gave her testimony. She said the captain had struck her four times, and she received no dinner or her money back. She also said: "I never, never use bad language, and do not recollect of doing it on that occasion. I was angry because I was refused, and the way I was spoken to." She admitted to holding on to the table as the clerk and captain removed her, causing the tablecloth to come off.

The verdict was in Coger's favor, and she was awarded $250. She said she had not sued for money's sake, but "to vindicate the rights of my race, and my character of womanhood," and she gave the entire sum to her lawyer. The defense appealed and filed a motion for a new trial. However, the laws of Iowa and the U.S. Constitution secured Coger's rights, and the motion was struck down in the Iowa Supreme Court.

The Quincy Daily Whig interviewed Coger's mother, Cynthia, about the incident in 1893, and she corroborated many facts given from a Keokuk Constitution article. Coger was teaching at an all-black school in Boonville, Mo., at the time, but would soon move back to Quincy. She died in 1924 in Quincy and is buried next to her mother in an unmarked grave in Woodland Cemetery. Her landmark civil rights case is still studied today.

Heather Bangert is involved with several local history projects. She is a member of Friends of the Log Cabins, has given tours at Woodland Cemetery and John Wood Mansion, and is an archaeological field/lab technician.

Sources

"A Bit of History That Will Interest Friends of Emma Coger: She Defended Her Rights" The Quincy Daily Whig, Oct. 17, 1893.

Emma Coger v. Northwestern Union Packet Company, Supreme Court of Iowa transcript.

Quincy City Directory 1872