The Achievement of John Longress

In 1882, an African American blacksmith born into slavery and prominent Adams County Republican, John Longress, secured a ruling from the Illinois Supreme Court that the Quincy school board could not “exclude children of African descent from admission to the public schools which are provided for white children.” Chief Justice Alfred M. Craig wrote that the Illinois Constitution of 1870 and an 1872 law required the legislature to “provide a thorough and efficient system of free schools, whereby all children of this State may receive a good common school education,” allowing “no distinction in regard to the race or color of the children of the State who are entitled to share in the benefits” of public education. This Illinois precedent anticipated the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 holding in Brown v Board of Education that “separate but equal” racial segregation of public-school students violated the federal Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection under law.

The historian John D. Coats has written, “By 1890 most of the county’s 2,044 African Americans lived in Quincy, where de facto segregation ensured that they would live in the northwest corner of the city.” In an earlier column in this series, Patrick McGinley wrote that Lincoln School, located at 10th and Spring, was established by the Quincy school board as the city’s “colored school.” The board mandated in 1880 that "no colored child shall be enrolled in any white school except for special permission, and no white child be enrolled in a colored school save by same dispensation.” In fact, McGinley found, 94 Black students were attending other schools with white students throughout the city, but the board wanted to segregate them with the 126 Black students already at Lincoln.

John Longress had tried to help his seven children, and other children in Quincy’s Black community, of which he was a leader. When he died suddenly on September 9, 1886, the Daily Whig , recognizing his “keen intelligence and force of character,” wrote, “Born a slave, he broke his own fetters, worked out his own freedom paying his owner a heavy ransom for the boon of freedom.”

Unfortunately, the legal system—at first—failed him and those for whom he advocated. The school board and the Adam County courts ignored the decision of the state supreme court. On June 1, 1908, the Daily Herald reported that, as the school board considered building a new Lincoln School, some Black parents objected to “having a separate school for their children” and asked that their children be “thrown into contact with the white children.” In short, more than 25 years after the Illinois Supreme Court had forbidden racial segregation in Quincy schools, Lincoln remained as segregated as it had been in 1882.

One parent, Aaron Brown, refused to send his children to Lincoln and, after a justice of the peace imposed a $10 fine in 1911, initiated a test case to the Illinois Supreme Court. This time—perhaps on procedural grounds—the court refused to intervene, a decision in sharp contrast to its action in litigation challenging segregation in Alton public schools. In 1899, parents had sued the Alton mayor and city council to compel admission of their children to integrated schools. That case required almost nine years of litigation, and four return trips to the court, before the Supreme Court issued an extraordinary “writ of mandamus”—an order directing local officials to perform their legal duties and admit the children to integrated schools.

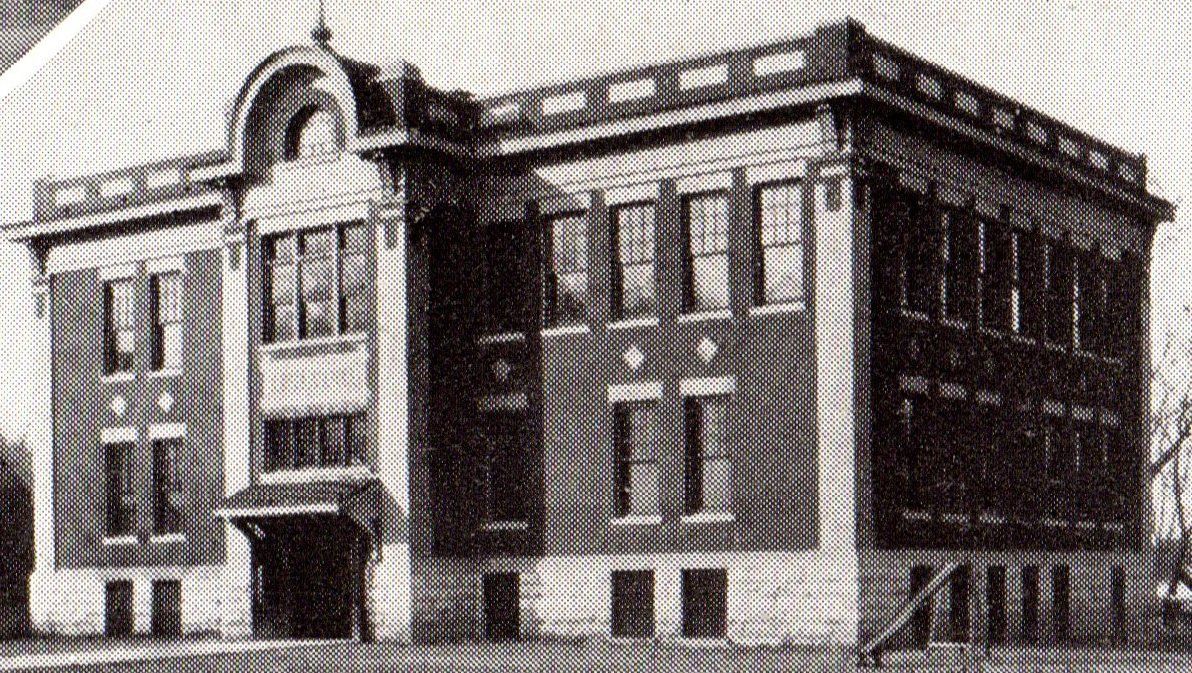

In Quincy, as decades passed, Lincoln remained as segregated as it had been in 1882 and 1911. In 1919, the Daily Whig reported that the local YMCA, after having invited the Lincoln basketball team to play in a tournament, barred the team from the floor because the players were Black. The newspaper reported that the “boys packed up their paraphernalla (sic) and left the building.” In1932, a Herald Whig story reported that a Quincy pastor was urging the school superintendent to restore an earlier policy allowing Lincoln athletes to compete in integrated interscholastic sports, and in 1936 the paper carried a photograph of “the present Lincoln school for colored children.”

The heritage of Lincoln School is complex. Its status as a symbol of Jim Crow should not overshadow the achievements of its parents and students who, the Quincy papers tell us, nevertheless supported its active and influential PTA, dedicated teachers, and champion basketball teams, while providing a central meeting place for their community. One of Lincoln School’s alumni grew up to become Quincy’s first Black pilot, a decorated war hero with a long career in military intelligence, and honoree of having a Quincy school named for him: Colonel George Iles.

If John Longress ever doubted that his litigation had been worthwhile, he would have been wrong. In 1953, the U.S. Supreme Court requested a submission from the Department of Justice addressing implementation of the Brown desegregation decree. Solicitor General Simon Sobeloff filed a brief, citing the Longress case as an example of state courts declaring public school segregation illegal under state, not federal, law. More recently, writing in the Yale Law Journal in 2019, California Supreme Justice Goodwin Liu recognized the case for the Illinois court’s statement that “[w]e base our decision on the constitution and laws of the State,” and its significance as one of the early “pro integration voices.”

The reasoning of judges may often seem abstract, but to mean anything, it must reflect the experiences of people. The slave who “broke his own fetters” and “worked out his own freedom paying his owner a heavy ransom for the boon of freedom” did, indeed, extend the freedom of others.

Sources

Brown v Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

Coats, John D, “A Question of Loyalty: The 1896 Election in Quincy, Illinois”, Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (Summer 2015) pp. 122, 127.

“Death of John S. Longress”, Quincy Daily Whig, (September 10, 1886) p.3.

“First Lincoln School Built in 1861”, Quincy Herald Whig, (February 16, 1936) p. 6.

Hon. Goodwin Liu, “Book Review: State Courts and Constitutional Structure”, 128 Yale Law Journal 1308, 1365 (2019}.

“Lincoln Team Barred from Local ‘Y’ Floor”, Quincy Daily Whig, (March 9, 1919) p.2.

McGinley, Patrick, “A Look at Lincoln School 1872--1957”, Quincy Herald Whig , October 30, 2020. https://www.whig.com/archive/article/lincoln-school-1872---1957/article_727765de-9497-5cb6-835a-788714d1db4d.html

Meier, August, and Elliott M. Rudwick, “Early Boycotts of Segregated Schools: the Alton, Illinois Case, 1897-1908”, The Journal of Negro Education, (Autumn, 1967), pp. 394-402

“Negro Was Fined”, Quincy Daily Herald, (January 16, 1911) p. 3.

People ex rel. Bibb v. Mayor & Common Council of Alton , 233 Ill. 542 (1908).

People ex rel. John Longress v. Board of Education of the City of Quincy, 101 Ill. 308, 313 (1882) (original emphasis).

“School Board Added Trouble” Quincy Daily Herald, (June 1, 1908) p.6.

“Starts Movement to Have Lincoln School Athletics”, Quincy Herald Whig, (October 17, 1932) p.10.

“Supplemental Brief for the United States on Reargument” in Brown litigation (November, 1953), at p.102. (available on Westlaw, 1953 WL 78291)