The great Quincy water wars of 1890-95

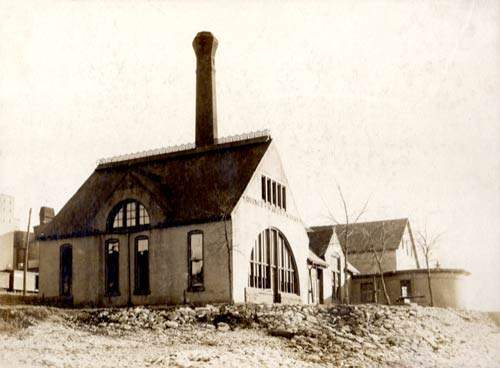

In 1871 the city created the Quincy Water Works Company, built a pumping station on the public levy at the foot of Maine Street, and installed a 30" wooden intake pipe in the Mississippi so river water could be pumped directly into water cisterns by hoses. But the city could not afford to make other needed improvements or lay water mains. In 1873, private entrepreneur Edward Prince acquired all rights to the company plus a thirty year contract to supply the city with water.

By 1890 the water company was still owned in part by Prince, but it was run by Lorenzo and William Bull who had become his partners. While the Bulls were great benefactors to Quincy, relations between the city government and these entrepreneurs were sometime rocky. The city was unhappy with smelly, dirty water, high rates and especially with the provision requiring fire hydrant installation fees of $75 each, plus a yearly rent, on top of the city's annual $10,000 water bill.

The company had ordered a filtration system which required a second pump to be installed on the public levy, though the actual filtering plant would be located on private property. The city fathers threatened to arrest William Bull if he took any more space on the levy. Bull cancelled all plans for filtration.

At the same time, the city demanded better terms and a new contract, while steadfastly declining to say specifically what they required. William Bull, who was in charge of daily operations at the company, would not separately change hydrant rates without a full contract insisting, "The tail goes with the hide ... I am tired of making supplemental agreements…"

This stalemate would hold through many elections, several mayors and multiple city council members. With the water question unsettled, streets remained unpaved, sewer lines were useless; businesses chose other places to locate and most of the 71 miles of city streets remained without fire hydrants. The city began to think again about building its own water works. And the populace drank river water.

In January of 1891 the Bulls again requested a thirty year contract stating they would reduce the minimum water rate from $5/quarter to $15/year; make extensions on the mains for a guarantee of $50/block (down from $100); and furnish water to the city for $10,000 annually. The water committee recommended building its own water works and against any new contract.

By May 1891 at a conference with Bull, the council demanded new rates, while dodging the question of filtered water. William Bull asked, "Do you want chemically pure water or water as it runs down the river?" Alderman Soebbing replied, "It is not quality that the people ask for, but low rates." Mr. Bull replied, "I gather from you that what is wanted is more water for less money regardless of quality." "Not exactly," was the reply.

William Bull did not trust the council, "I was arrested last fall. I would rather not have that happen again." He requested that his rights be spelled out, that two lawsuits the city had brought against him be dropped, and in return he would reduce the water rates and extend the 27 miles of water mains and possibly install a filtration plant. The committee adjourned with no decision.

By July, 1891 the city was discussing individual water fees based on the number of rooms in a house and the length of street frontage. Bull offered to sell the company to the city but would not commit to lower rates without a contract. All talk of filtration was off the table.

Then the so-called McCrone Law, House Bill 93, was passed by the Illinois legislature saying a city could set its own utility rates, forcing private providers to comply or appeal to the circuit court. George McCrone was the Quincy lawmaker responsible for this legislation. The Bulls, with their pre-existing 1873 contract, would certainly appeal all the way to the Supreme Court, creating immense legal expenses and years in court while the existing rates would still apply. All decisions were again postponed.

Meanwhile the city mains delivered plain unfiltered river water; William Bull took a vacation; the Journal published a scathing parody about a body found in the water reservoir; and there were complaints that even horses that pulled the American Express wagons would not drink city water. The council in August, voted to have the water analyzed. No surprise, it was judged contaminated.

"In the mean time we will all drink beer," recommended Alderman Fischer.

The Bulls moved the intake valve for their pumps away from the Broadway sewer and out into the channel near Pier 8 of the bridge. Meanwhile, the city sued them over hydrant prices and scheduled an election on building a city water works. In an anemic voter turnout, that proposal lost.

By December of 1891 the Bulls decided to install Jewel Gravity Water Filters and keep the current rates despite a claimed cost increase of nearly 50 percent. Even with no progress on a contract, by August, 1892, the mains were running water filtered through 30 inches of quartz sand. But since the mains had not been flushed, the improvement was marginal. The sand filters were cleaned once a day.

In May of 1893, facing the expiration of the supplemental water contract, the council advised the mayor to stop paying for water when the contract expired. The Whig charged in an editorial in June of 1893, that the Bulls' demand for payment in advance from the city was "cheeky,"and called the council "bipedal jellyfish" for not opposing these arrangements.

In August, the city did stop paying their water bills in advance, and additionally, decided to charge the Bulls for their space on the levy. In response, Bull raised the annual rate to the city from $10,000 to $12,000, due in advance. On October 30, 1893, one headline read: "The Water War Opens."

When they failed to collect the $1,000 due from the city, the Bulls' workman calmly removed a section of paving out near the street car track and shut off the water line to city hall. The mayor had the workman arrested. But under a decree from 1883 the city was forbidden to interfere with the water company as it installed or shut off any water main. The mayor got an injunction.

Mr. Bull declared that his decree superseded the injunction and demanded payment from the city. The Water Committee threw up its hands, dumped the problem in the mayor's lap and adjourned.

Eventually the Bulls did turn the water back on, but wrangling continued until April 1895 when a contract favorable to the city was finally agreed upon.

Then the controversy simply shifted to a price which the Bulls would accept to transfer ownership to the city. This next stage occupied almost another decade until the city finally purchased the company in 1904 and ended the water wars.

Beth Lane is a member of the Historical Society and author of "Lies Told Under Oath," the true story of the Pfanschmidt murders. She recently moved here from Arizona, where she was involved in the Society of Southwestern Authors, the Arizona Mystery Writers, and led writing workshops.

Sources

"A Good Beginning." Quincy Daily Journal. January 23, 1891.

"About Water Rates." Quincy Daily Whig. July 9, 1893.

"About Water Works." Quincy Daily Journal. January 7, 1891.

"At Last She Filts." Quincy Herald. August 16, 1892.

"Brought to an Issue." Quincy Daily Whig. July 25, 1893.

"Chose the Sword." Quincy Daily Journal. July 14, 1891.

Collins, William H. and Cicero F. Perry. Past and present of the City of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois. Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1905

"Comparing Rates." Quincy Daily Whig. May 28, 1893.

"Don't Want Water." Quincy Herald. November 18, 1891.

"It must Pay Rent." Quincy Morning Whig. August 24, 1893.

"Lower Water Rates Assured." Quincy Daily Whig. July 7, 1891.

"Mayor Walker." Quincy Daily Journal. October 5, 1891.

"Must Have his Money." Quincy Morning Whig. October 30, 1893.

"On Water Works." Quincy Daily Herald. October 4, 1890.

"Purified Water." Quincy Daily Whig. December 11, 1891.

"Special Committee." Quincy Daily Journal. January 20, 1891.

"Straight to the Mark." Quincy Daily Journal. September 18, 1891.

"Talking about Water." Quincy Daily Whig. October 4, 1890.

"Tempe's Body." Quincy Daily Journal. August 21, 1891.

"The Bulls Arrested." Quincy Daily Herald. October 30, 1893.

"The People." Quincy Daily Journal. January 18, 1891.