Town provided refuge for persecuted Mormons

The city of Quincy has always been a welcoming community, but never more so than during the winter of 1838-1839 when the residents provided aid, shelter, and comfort to the distressed Mormons who were fleeing persecution in Missouri. The hospitality shown to the Mormons has never been forgotten by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latterday Saints, but Quincy residents might not be familiar with one of the Gem City’s finer moments.

In the early 1830s Joseph Smith led his followers across the

Mississippi River and established settlements throughout Missouri. Hoping to

live peacefully, the Mormons met with fierce resistance from many who were

intolerant of their faith. Over the course of several years, the Mormons

struggled to locate an area where they could worship freely.

Granted land in Caldwell by the Missouri legislature in 1836, the Mormons enjoyed relative tranquility until 1838 when conflict with neighbors erupted. Violence soon ensued, and the “Missouri Mormon War of 1838” commenced. The war lasted several months with the Missouri militia and the Mormons battling each other.

On Oct. 27, 1838, Gov. Lilburn W. Boggs issued an executive

order banishing the Saints from Missouri. On Nov. 1 the Saints surrendered, and

Joseph Smith along with his brother Hyrum, Sydney Rigdon, and other Mormon

leaders were charged with capital crimes and were incarcerated in a Liberty,

Mo., jail.

Faced with expulsion, thousands of Saints headed east for Quincy. Their motives for choosing Quincy varied, but Quincy made sense for a number of reasons. Although small, numbering only about 1,600 in 1839, the city was growing. Further, Quincy had a reputation for being a tolerant place, one where social outsiders could be welcomed.

Beginning in late 1838 the first settlers arrived, and an estimated 6,000 would come east across the Mississippi during the winter of 1838-1839. Their passage was by no means easy. Crossing the Mississippi in winter can be treacherous, but fortunately all making the trip, whether by canoe or by their own feet when the great river froze over, survived.

Quincy and the surrounding areas were a haven for the Mormons, as they found the people warm and welcoming. Housing was provided for them, and funds were raised by the city’s population. By April there were thousands more Mormon refugees than permanent residents, but all were provided for.

Many of Quincy’s political figures did all they could for the refugees, not in the least because the Mormons were an important and sizable political bloc. The city’s founder, John Wood, was a friend and benefactor to the Mormons. As mayor of Quincy in 1839, Wood helped raise money for the displaced Saints, and he would later try and prevent an anti-Mormon militia from attacking Mormons in Nauvoo.

When the Mormons were driven out of Nauvoo in 1846, Wood again came to their aid. He and other leaders gave the fleeing Mormons material comfort such as food, medicine, and blankets. Other prominent Quincyans, including Orville Hickman Browning, Archibald Williams, and Henry Asbury, also helped out.

The Mormons stayed in Quincy until May 1839. A month earlier they were joined by Joseph Smith, who had been imprisoned in a Missouri jail. Upon his releases, Joseph along with his brother, Hyrum, and several other church leaders had immediately set out for Quincy. Smith’s time in Quincy was relatively brief, for he had already planned yet another move, this time north.

Prior to arriving, he had purchased land about 40 miles north of Quincy, where he and his followers would settle. The Mormons began their trek to Hancock County, and they settled on the banks of the Mississippi River at the city of Commerce, later named Nauvoo.

Smith expressed his gratitude to the people of Quincy in a letter to the Quincy Whig, dated May 17, 1839: “The determined stand in this State, and by the people of Quincy in particular, made against the lawless outrages of the Missouri mobbers ... have entitled them equally to our thanks and our professional regard.”

The story does not end in 1839. For several years the new community in Nauvoo flourished, but dissent among the Saints brought about controversy, which culminated in the arrest of Joseph and Hyrum Smith for smashing the press of an anti-Mormon newspaper in the city. In June 1844 a mob attacked the jail in Carthage, killing both Smiths. The murder did not end the tension in the community, and by 1845 the “Battle of Nauvoo” or the “Mormon War in Illinois” had begun. In October 1845 the “Quincy Committee” entered into negotiations with the Mormons to end the conflict, which would mean that the Latter-day Saints would have to depart from Nauvoo.

The committee ensured that the mobs in the surrounding areas, particularly from Warsaw and Carthage, would leave the Mormons alone while they departed Illinois. The Quincy Committee saved more bloodshed and allowed the Mormons to start on their westward trek to what is now the home of Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Luckily, parts of the Mormon experience in the Quincy and Tri-state area have been preserved. In 1976 the Latter-day Saints dedicated a historical marker in Washington Park. “The Mormons in Quincy” provides a brief summary of the time spent in Quincy and the everlasting gratitude of the Mormons for the people of Quincy. Visitors to the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County at 12th and State can see artifacts from that time.

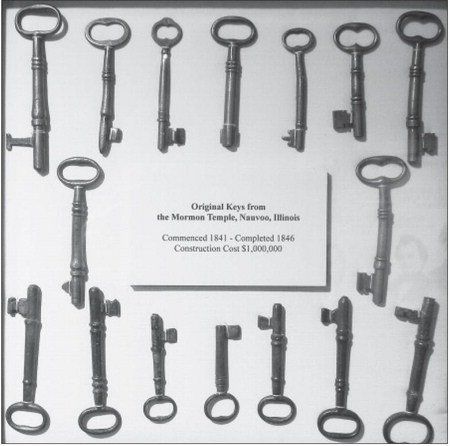

The Visitors Center houses keys to the original Mormon Temple in Nauvoo. As the Latter-day Saints left Nauvoo for the Utah Basin, they made a gift to Artois Hamilton, an innkeeper who took care of Joseph and Hiram Smith’s bodies the night after they were murdered in Carthage.

Hamilton built coffins for the brothers and transported them to Nauvoo. The set of 16 keys, given as a gift from Mrs. E.B. Hamilton to the Historical Society, are available for viewing in the Society’s Lincoln Gallery. These keys help show that the city of Quincy is an important part of the history of the Mormon Church, a legacy that is still alive today.

Justin P. Coffey is associate professor of history at Quincy

University. He is the author of numerous articles on American history and is on

the board of the Historical Society.

Sources

Black, Susan Easton and Richard E. Bennet, eds. A City of Refuge: Quincy, IL. Riverton: Millennial Press, 2000.

Hallwas, John E. and Roger D. Lanius, eds. Cultures in Conflict: A Documentary History of the Mormon War in Illinois. Logan: Utah State University Press, 1995.