Unitarian minister's diary tells of life in 1840s

Thankfully, George Moore kept a diary in which he recorded many interesting, if often incomplete descriptions of life in early Quincy and its inhabitants.

He was ordained at Harvard University on Nov. 4, 1840, “intending to take the ministerial charge of the Unitarian Society in the city of Quincy, Ills. For the coming winter.…”

Because Moore had been in the company of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, his diary was later published.

Moore remained in Boston to vote in the presidential election and complete his travel arrangements, for which he received $50 to defray expenses. For his salary, the new Quincy congregation would contribute $300, and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel would add $250. This was well below the normal stipend for ministers. Moore left Concord, Mass., on Nov. 10 and arrived in Quincy on Dec. 1. He broke his journey at Worcester, Mass., then Philadelphia, on to Chambersburg, Pa., then “the smoky city of Pittsburgh.”

He left Pittsburgh on the steamer Fulton for Louisville, Ky., where he stayed for four days; then took the steamer Express to St. Louis, where he stayed for a couple of days before boarding the steamer Rosalie, which struggled through ice to reach Quincy.

Moore settled in at Quincy House, where Mr. Munroe, the landlord and his family were Unitarians, and set a fine table. Moore’s diary recorded, “I came not to the west with any expectation of making money – that I came to join my fortune with that of the little band of the faithful here, and to take from them only that which they found convenient to pay.…”

Moore moved first into room No. 41 at Quincy House for $4 a week, which included meals. “Here I am living very cozily in a room 10 feet by 6, or thereabouts. It has a large wardrobe connected to it, and is warmed by a tall, square, sheet-iron stove. Here I am to manufacture my sermons for the winter and to do most of my labor.”

The following day Moore wrote, “Have had another move, today, into No. 72 in the fourth story. Mr. Munroe thought my quarters too confined, and very kindly gave me a room of about twice the size of the other.”

On Dec. 15, Moore walked 2 miles “upon the prairie” to visit one of the area schools where Presbyterian missionaries are trained. Institute No. 4 held 34 young women and 32 young men taught by the Rev. Hunter and the Rev. Beardsley. Moore observed, “Rev. Mr. Hunter is a singular old man. He dresses in a course garb of grey cloth — a sort of frock-coat, with only one button at the top, and a girdle round the waist — a vest made whole in front, without a button — and a cloth cap. He seems to be a disciple of John the Baptist.”

He learned that the institute asked no tuition and provided some education and much work. Students were required to build their own houses and provide for their own support.

The students were given Saturdays free from study, and they worked that day as laborers for area farmers in order to earn food for the week. They were given about three months’ vacation during the year, and by working during that time could provide themselves with clothing for the year.

The local farmers paid the men about 75 cents to a dollar per day, and the young women washed and sewed for the young men in order to earn their support money. In this way all could afford to come and be educated.

Moore came away impressed by the “truly democratic institution” and the devotion to education. He wistfully wrote, “Would that our denomination might have something similar to this, where young men, at least, might prepare themselves for the gospel ministry.”

In early January of 1841, Moore attended a Mormon meeting in which various men stood to expound upon different doctrines. The Harvard-trained Moore was not impressed by their speaking style, nor the small room lit by tallow candles, but the hymns were “lively.”

“I don’t know that I ever before saw such a congregation of stolid faces…. The meeting continued for two and a half hours and the air of the room became very impure.” He went on to confess disappointment, saying that “I hoped to hear some one speak the ‘unknown tongue’ — this is frequently done at their meetings.”

Moore himself was teaching a Bible study class and preaching two sermons on Sundays or attending other church services, calling on prospective church members and trying, mostly unsuccessfully, to write his next sermon.

Toward the end of January, Moore reported an outing through the cold winter weather to a home nine and a half miles north of Quincy. Mr. Munroe had arranged a double sleigh and a “span of fleet horses” to carry six guests, including Moore, to a fine Sunday dinner at the home of Mr. Murphy.

The menu included both a baked turkey and a goose, plus meat and apple pies, all served in the big farmhouse kitchen. The guests were glad to assemble in front of the fireplace, which was large enough to accommodate hickory logs 5 feet in length. It took about two hours travel time each way in the sleigh.

On the evening of Feb. 22, George Washington’s birthday, Moore recorded that there were two balls held in Quincy House, after concerts in the morning and afternoon and a parade. He listened to the band music from his room, and admitted to feeling vaguely discontent. A week later he reported taking a horseback ride “on one of Mr. Munroe’s hard trotting horses. I never rode so hard a horse before. But I thought the ride would do me good, and I went in all 8 miles. It was doing penance, but I feel better for it, and hope to continue this kind of exercise. It would strengthen my outer man much.”

On May 4, 1841, he celebrated his 30th birthday in Quincy, and determined that he had become a man.

“When 30 years stare one in the face, he can no longer feel himself a ‘boy’ he is a man, whether he be manly or not. And I am a man.” He conducted an inventory of his life, concluding by looking forward hoping that, ‘I might make this year the most useful of my years — indeed that I might accomplish a greater and better work than in my whole past life.”

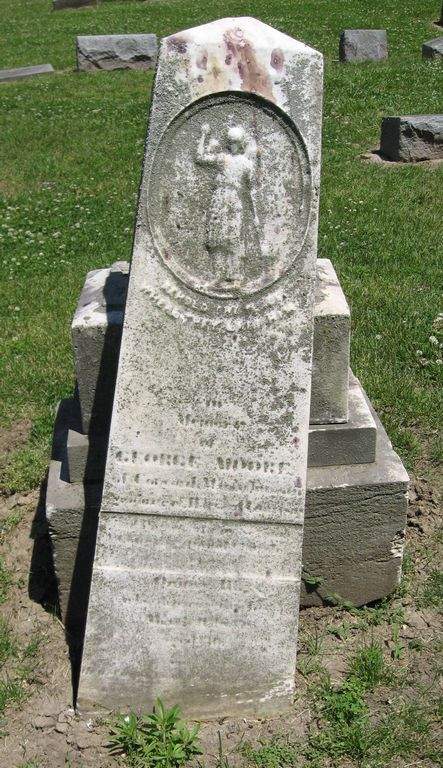

George Moore would spend the next six years in Quincy, until his death in 1847. His diary continued until the end of his life.

Beth Lane is the author of “Lies Told Under Oath,” the story of the 1912 Pfanschmidt murders near Payson. She is the former executive director of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

Sources:

“Transcendental Epilogue Primary Materials for Research in Emerson Thoreau, Literary New England, the Influence of German Theology and Higher Biblical Criticism” by Kenneth Walter Cameron, Vol. I.

“Quincy Unitarian Church, 175 Years in Quincy, Illinois” by Dienna Danhaus Drew and Freida Dege Marshall.