Victorian mourning rituals tightly scripted

Every culture has its own way of dealing with a death.

Victorian-Era Americans in Quincy were no different. The Victorian Era covered the period during Queen Victoria’s reign, roughly 1837-1900. Her Majesty’s influence was felt far and wide, even across the ocean in America. This influence included the proper way to mourn.

These rules applied mostly to women because men could not be expected to take time away from their busy lives to mourn. Men’s mourning dress consisted of the same grey or black suits they wore every day. They could add a black armband from one to three months if they so chose. Moreover, men could prove their worth by being able to remarry quickly after losing their wives.

Women’s mourning dress

On the other hand, women’s rituals involved more elaborate dress for longer periods of time. Depending on a woman’s relation to the deceased and her socioeconomic status, mourning could be more or less intricate. For example, women mourned their parents for around three months. They mourned a cousin or distant relative from two to six weeks. However, wives mourned husbands for up to two years.

A woman divided these two years into periods of deep or total mourning and light or half mourning. Traditionally, deep mourning lasted for one year and one day. Many women stayed in a state of total mourning for their entire lives, though they did rejoin society.

Women’s mourning clothes were black from head to toe. Some think this comes from the tradition of the Romans wearing black togas in times of mourning. The color black also represented the absence of light and life. Victorian mourning dress became known as “widow’s weeds” because the material used for the veil would tatter and begin smelling like rotting weeds.

Class differences in apparel

For middle and upper class women, it was important to wear a black bonnet made from crepe, silk, or cotton. The bonnet had a “weeping veil” attached to it. The veil could be as long as the woman wanted; veil length ranged from shoulder length to the bottom of the lady’s dress. A woman could include black accessories like gloves, shawls, or mitts. Jet jewelry and buttons finished the look, although most women did not wear any jewelry during deep mourning.

Lower class women had fewer choices when they had to mourn. They wore a simple black cotton or wool dress. They attached a crepe veil to their hair with a small headpiece or bonnet. They usually wore the same dress for every occasion of mourning, unlike the upper class women who had a different mourning dress for every instance.

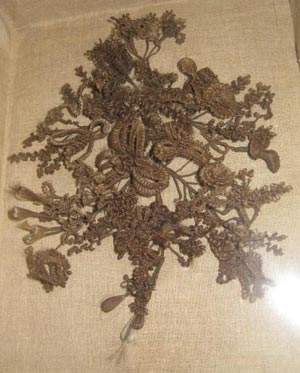

Every class used hair as an accessory. Hair jewelry and hair wreaths became very popular during the Victorian Era. The Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County has two such hair wreaths on display in the History Museum. A woman could custom order mourning jewelry from a jeweler. A popular item with the wealthy was a hair brooch set in gold.

Social expectations

Aside from her personal dress, a woman had certain social expectations when dealing with a death. Within 24 hours she was expected to cancel all social activities. Callers could come to the house but were most often received by other family members, typically male relatives. Women could see servants daily, as the household needed running. The servants were also expected to enter mourning for their employer and stay in mourning for as long as the family mourned. Again, men did not have such restrictions because they had to go to work and conduct business out in the public sphere.

While in deep mourning women had to avoid public meetings, frivolous shopping trips, and teas or parties. Victorians considered it bad luck for a woman in widow’s weeds to attend a wedding. If she absolutely had to attend, she could either set them aside for the ceremony or attend in “absentia.” For instance, Queen Victoria attended her son’s wedding in deep mourning but sat apart from everyone and she did not attend the reception.

Public signs of mourning

Custom required that even the home display appropriate signs of mourning. The windows and mirrors of the house were covered with crepe. They thought this prevented the soul of the deceased from being trapped. It also showed that members of the household were not concerned with personal vanity during their time of mourning.

As a signal to neighbors, black wreaths of silk and wax flowers were hung on the front door and mantles. The Historical Society continues to honor this tradition at times, recently using black crepe draping on its front doors and fences upon the death of its executive director.

If the deceased was a resident of the house, the body would be laid out in the parlor or bedroom. The family kept a vigil 24 hours a day for one to four days. This “waking,” or wake, allowed the family to show respect for the dead. The wake also helped ensure that the person was actually dead, since premature burial did happen. A funeral or burial service followed the vigil. A person only attended a funeral if invited, but once invited one was expected to attend.

Park-like cemeteries

Victorian cemeteries took on a particular look and feel. Public cemeteries became more popular because churchyards were becoming overcrowded and unsanitary. People placed their cemeteries in the countryside at first just to keep them away from the city.

Over time, they decided that the pastoral setting created a relaxing atmosphere in which they could mourn. So, they began to plan cemeteries like parks, complete with benches, walkways, and gardens.

Quincy’s Woodland Cemetery, begun in 1846, provides a perfect example of a Victorian cemetery. Descendants of families like John Wood’s and Orville and Eliza Browning’s are buried along walkways in Woodland.

Light mourning transition

After deep mourning, a woman could “come out” to light or half mourning. During this period, women could set aside their weeping veil and add trims and jewelry to their wardrobe.

Over several months they could gradually move from darker shades of grey and violet into lighter shades of grey and lavender. Eventually, they could use other colors and abandon mourning dress altogether.

Furthermore, during light mourning women could return social calls, attend church functions and visit relatives. Widows were expected to travel with a female chaperone. During the Civil War, many of these societal rules were relaxed because women’s activities outside the home, like the Needle Pickets, were seen as charity work and not as frivolous socializing.

While not all mourning traditions survive in the 21st century, many of the modern customs find their roots in the Victorian era.

Bridget Quinlivan is a recent history graduate from Quincy University and Western Illinois University. She is a volunteer and seasonal employee at the Historical Society and an English/writing specialist for Student Support Services at John Wood Community College.

Sources

Mehaffey, Karen Rae. The After-Life, Mourning Rituals and the Mid-Victorians. Laser Writers Publishing, 1993.

Winkelmann, Judith. "Mourning, Majesty, and Mary Lincoln." Quincy, IL: Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, August 1997.