When Quincyans attempted to be peacemakers

Summary of Part 1 published in June:

After Joseph Smith, founder of Mormonism, declared that Missouri was the location of the Garden of Eden and the stones Adam used for worship were still there, thousands of Mormons poured into the state with beliefs that set them at odds with the "old settlers."

In October 1838, the governor of Missouri decreed that all Mormons must leave by spring on penalty of death. Approximately 5,000 Mormons headed for Quincy and Adams County. Quincy sheltered them by whatever means possible.

Joseph Smith arrived in Quincy in the spring and led his people 47 miles north to Nauvoo. Soon Mormon settlements were scattered over several counties in Illinois and Iowa, and the years ahead were characterized by constant conflict between the Mormons and their neighbors that continued under Brigham Young's leadership after Joseph's death in 1844.

On Sept. 11, 1845, a public meeting was held in the courthouse in Quincy and a solemn resolution was passed. The resolution implored the Mormons to go somewhere in which they would "not be likely to engender so much strife and contention as so unhappily exists at this time in Hancock and some of the adjoining counties."

Seven Quincy men delivered the resolution to the Mormon leaders Sept. 23, 1845, and received a formally written response the next day. It stated the Mormons' intentions to move to "some point so remote" they would no longer be troubled, the following spring. They were specific that it would not be before the grass was growing, or water flowing, but asked for peace until then, and help in liquidating their possessions. In October 1845, at a meeting in Carthage, nine other counties "accepted the pledges made by the Mormons." Everyone hoped for peace.

Part 2:

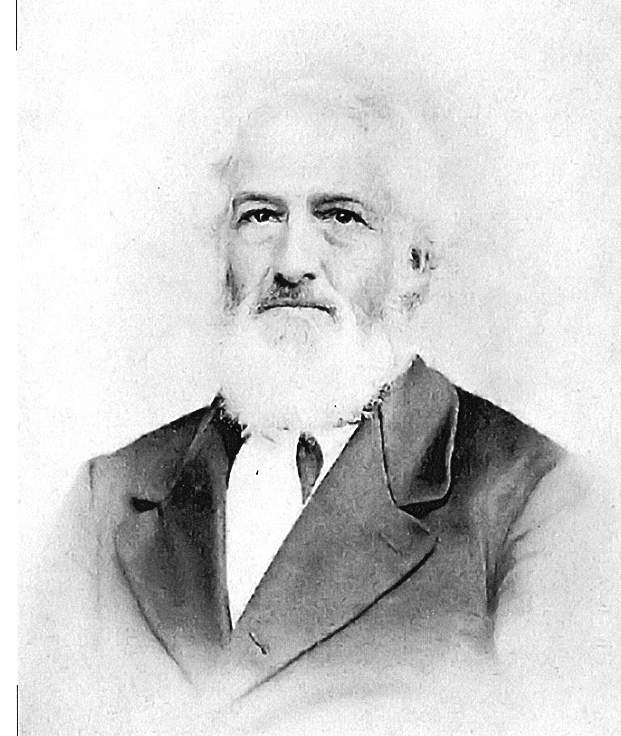

Henry Asbury, one of the Quincy men who had delivered the message and taken the Mormon response back, left a detailed record: "For a time, comparative peace reigned … but when September of the next year, 1846, came and after grass grew and water ran, it was found that only a portion, though a large portion, of the Mormons had left the State for their newly chosen home near Salt Lake."

Two migrations totaling nearly 15,000 Mormons had left Nauvoo already, but Asbury believed that only those too weak or having the least to contribute, whom he termed "the poorest and perhaps most worthless" remained, and showed little intention of leaving. Arrest warrants were sworn against some of the Nauvoo citizens, and state militia Col.Tom Brockman, a "sturdy blacksmith from Brown County," led approximately 800 men to execute the warrants. The Mormon population of Nauvoo was estimated to be 150.

Brockman's militia arrived near Nauvoo on Friday, Sept. 11. He demanded that the citizens surrender. They refused, and on the 12th the "battle of Nauvoo" was fought, with casualties on both sides. Word of the skirmish reached Quincy the next day, and caused significant alarm. The Quincy leaders feared that if the militia overran the town, a massacre including women and children might occur.

That Sunday afternoon Asbury and the Honorable I. N. Morris agreed to raise a group to go and intervene, and went from house to house gathering people for a meeting in the courthouse that evening. There, a committee of 100 men was appointed to leave for Hancock County. "The committee had no thought that they could dictate terms to the parties engaged in the contest. Their main idea and purpose was to stop the war."

The committee sent word ahead to both Brockman and the Nauvoo citizens of their intention and the fact that they were coming unarmed. They encamped about 2-1/2 miles east of the town and sent representatives to both sides of the conflict, an action that was repeated multiple times as negotiations progressed. Asbury served at various times on both the committees of negotiators. A negotiated cease-fire failed and "in one instance a 6-pound shot fell near the Mormon headquarters whilst some of the committee were in them."

Proposals from the two sides were carried back and forth with no agreement. Finally, the committee from Quincy took its own proposal to both. It included the requirement that the Mormons leave, but the inhabitants of Nauvoo were "not to be hurried off in a day." Nauvoo accepted it, but Brockman refused. Brockman issued an ultimatum stating that his militia would march into Nauvoo at noon the next day. With few options, the Nauvoo leaders accepted Brockman's terms. Andrew Johnston, secretary of the Quincy 100, drew them up as a treaty.

The leaders of Brockman's camp signed the treaty, and although it was late in the day, Johnston, Morris, Asbury, and a few others, rode to Nauvoo and got the signatures there, thus avoiding more bloodshed. One problem remained: The Quincy men had to find their way back to their camp after 11 p.m. on a night Asbury claimed was one of the darkest nights he had ever seen.

The men became completely lost. The weather turned rainy and cold. They had no blankets, and some had no coats. They found an abandoned house and took shelter, but spent a miserable night before finding their camp.

Asbury wrote, "Brockman marshaled his hosts and started for Nauvoo, our committee bringing up the rear of the procession, and now like the little boy, had nothing to say. In fact, kind reader, our committee, consisting of one hundred of as good men as ever resided in Quincy, with all their good intentions to prevent the further shedding of blood, and with no thought or desire that the Mormons should permanently remain in Nauvoo, but that they should not be hurried off in a day, found themselves without honor of credit for good intentions by either party or by our Governor … I deem it but an act of justice, at least to the Quincy committee, to state its part in that memorable event of what is called the expulsion of the Mormons from Nauvoo, in September, 1846."

Linda Riggs Mayfield is a researcher, writer, and online consultant for doctoral scholars and authors. She retired from the associate faculty of Blessing-Rieman College of Nursing, and serves on the board of the Historical Society.