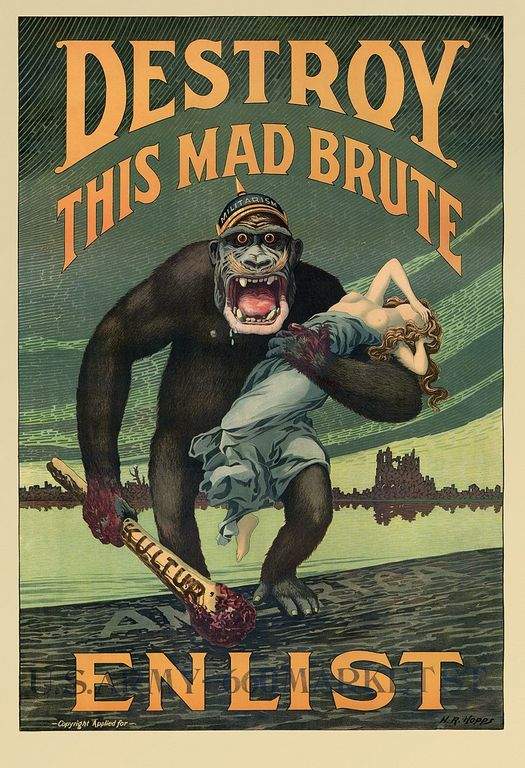

World War I unleashed anti-German hysteria

The United States' involvement in the Great War (later known as World War I) aligned our country with Allied forces fighting principally against Germany. It began April 6, 1917, and lasted until the war ended Nov. 11, 1918.

Long before and after those dates, though, anti-German sentiment directed mostly at naturalized American citizens spread over Quincy--as well as the rest of the country--and led to ostracizing, hostility and sometimes, arrests.

About 10,000 Germans immigrated to Quincy between 1829 and 1870, and when the United States entered the war, about one-third of the city's population had been born in Germany or in America with one or two native German parents. Quincy's German heritage ran so deep that on April 3, 1914, as war brewed in Europe, F.C. Klene, general manager of Germania, the local German language newspaper, issued a call to

German natives living in the Gem City to "report at once to the nearest consulate by mail for service in the German army."

After the U.S. entered the war, though, the national rallying cry of "100% Americanism" and the passage of the Sedition and Espionage Acts by Congress released a vicious attack against these citizens and their cultural heritage.

As doctors renamed the childhood disease of German measles "Liberty measles" and sauerkraut became "Liberty sausage," a rumor spread across the nation that Germans had created and released the worldwide influenza epidemic to further their war effort.

After three Quincy soldiers training at Camp Grant, Ill., died from influenza, The Quincy Daily Herald quoted an American officer: "It is quite possible that the epidemic was started by Huns set ashore by Boche submarine commanders."

At Quincy's St. Francis Solanus Church socials, the traditional fare of frankfurters and beer became wieners and "prohibitionist water." Detractors coined this term to denigrate German beer barons who had established businesses in the United States, and it rekindled the Prohibition movement begun in the late 19th century. As with all beer manufacturers, Quincy's Dick's Brewery lowered its alcohol content to 23/4 percent after Congress passed a bill restricting the fermentation of beer.

The city's oldest German fraternal society, Turnverein, changed its name to Turner Society and its headquarters to Turner Hall. The Quincy Daily Herald reported, "Among the Turners the word ‘verein' is taboo. It came from Germany and Germany is the country that has been killing and maiming the young men of America."

In April 1918, the Quincy Board of Education banned the teaching of the German language and the employment of anyone sympathetic to the enemy. Before long, the German Methodist Church held its last services in German and changed its name to Kentucky Street Methodist Church.

The Quincy City Council, with support from the Chamber of Commerce, unanimously voted June 11, 1918, to ban German magazines, newspapers and books from the Free Public Library. Soon afterward a German book burning took place near Washington Park.

Quincy's Labor Temple at Ninth and State, headquarters for the city's labor unions, included in its ranks some socialists. Public talks on socialism stopped. Germania ceased publishing in the spring of 1918, just as the American Protective League formed a chapter in Quincy to enforce loyalty. The league embraced its slogan: "If you can't fight over there, fight over here."

Officials arrested Theodore Pape, a prominent lawyer of German descent, for making what they perceived as disloyal remarks and refusing to buy liberty bonds.

Quincy Mayor John A. Thompson, along with more than a dozen prominent citizens, petitioned President Woodrow Wilson to imprison Pape in an internment camp as a war criminal. The mayor further ordered Quincy police to have Winchester rifles in place against a possible outbreak of violence.

President Wilson himself inflamed feelings toward German-Americans with his statement, "Any man who carries a hyphen about with him carries a dagger that he is ready to plunge into the vitals of the Republic whenever he gets ready." This belief swiftly spread to the local level.

After Wilson labeled immigrants without American citizenship "enemy aliens," Quincy authorities registered and created dossiers on 133 undocumented residents. At a Quincy City Council meeting, Alderman Simmons further moved to give all aldermen forms for their constituents to sign proclaiming loyalty to the government.

When German-American disloyalty appeared to threaten the security of Quincy and the nation, a Quincy Daily Journal editorial on March 30, 1918, stated: "People of Quincy, the enemy is upon us! We are as much a part of the battle as if we were fighting the foe on the battlefield. Sedition and arson and pro-German crime must be wiped from the face of our fair land. ... The time to strike is at hand. Our government has been lenient with these low reptiles long enough. It must stop."

This warning ominously resonated in the Quincy area. Both Quincy and Hannibal had active Ku Klux Klan organizations, and with their long-held motto of "100% Americanism" dovetailing with the war's slogan and the country's anti-German fervor, these chapters flourished during the war.

Quincy Manager Nick Kahl renamed his interleague baseball team that played in Baldwin Park "Ku Klux Klan."

After President Wilson praised the movie "Birth of a Nation," which glorified the KKK as America's saviors, The Quincy Daily Herald's review of the Empire Theatre's premiere of the movie called it the "greatest of dramas."

Before the war, Quincy's Salem Church proudly used a rare German Bible, autographed by Kaiser Wilhelm II, leader of the German people, for services. Little did the church or the city know that soon Wilhelm would become the most hated man in America.

Quincy school children as young as "beginner's school" (officials would ban the German word "kindergarten") would bring tin cans to school in a campaign to "Tie a Can to the Kaiser" by collecting metal for the American war effort.

With the war's end, Quincy returned to normalcy and as the years passed, the city again began to show pride in its German heritage.

Joseph Newkirk is a local writer and photographer whose work has been widely published as a contributor to literary magazines, as a correspondent for Catholic Times, and for the past 23 years as a writer for the Library of Congress' Veterans History Project. He is a member of the reorganized Quincy Bicycle Club and has logged more than 10,000 miles on bicycles in his life.

Sources:

"Even Influenza Won't Touch the Boches." Quincy Daily Herald, Oct. 5, 1918, p. 10.

"Greatest of Dramas." Quincy Daily Herald, Dec. 27, 1915, p. 3.

"Issue Call to Germans." Quincy Daily Herald, Aug. 3, 1914, p. 4.

"Last German Service Held." Quincy Daily Herald, Feb. 18, 1918, p. 11.

Lock, Larry. "Quincy and Adams County in The First World War," in People's History of Quincy and Adams County: A Sesquicentennial History, the Rev. Landry Genosky, ed. Quincy, Ill.: Jost & Kiefer Printing Co., 1974, pp. 487-92.

Meyers, G.J. The World Remade: America in World War I (book on tape). New York: Penguin Random House Audio Publishing Group, 2016.

"Our Fight at Home." Quincy Daily Journal, March 30, 1918, p. 6.

"Quincy Men Seek to Have Theodore Pape Interned by Wilson." Quincy Daily Whig, April 19, 1918, p. 3.

The Great War: An American Experience. Stephen Ives (principal writer) PBS Video, 2017.

"The WWI Home Front: War Hysteria & the Persecution of German-Americans." historyonthenet.com/" www.historyonthenet.com .

"What Kept Council Busy Last Night." Quincy Daily Herald, Dec. 11, 1917, p. 11.

"Word ‘Verein' is Dropped by Turners." Quincy Daily Herald, Dec. 9, 1918, p. 4.