You might say city once lived high on the hog

In 1825, about 70 homes occupied the newly established county of Adams in Illinois. The town of Quincy grew from one resident in 1825 to 700 in 1835. One pork-packing house, as well as 10 stores, a post office and 14 shops were established.

According to the 1905 book "Past & Present of the City of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois," by William H. Collins and Cicero F. Perry, for the first few years, the town's first butcher "spiked a wooden bar to a tree in the square and hung his meat on it. When the community consumed the meat that was hung, he killed another animal."

In October 1833, Capt. Nathaniel Pease arrived in Quincy and bought 300 hogs that were slaughtered, packed and shipped. Pease realized the potential of meatpacking and returned to his home in Cambridge, Mass., to bring his family to Quincy. In Massachusetts he told his story to a young Edward Wells, who had apprenticed as a cooper. Wells came to Quincy, and in 1835 formed a partnership with James D. Morgan in the cooper business.

In 1835, Pease's Pork Packing Co. purchased 3,300 hogs, which averaged 175 to 200 pounds each, and he paid the farmers $2.50 to $3 per hundredweight. He also purchased 40 head of cattle. During the year, he packed 900 barrels of beef and pork and 200,000 to 250,000 pounds of bacon, 1,300 kegs of lard and from 1,500 to 2,000 pounds of tallow.

Many barrels of pork packed in Quincy traveled down the river by steamboat to St. Louis and New Orleans.

After a few years in the cooper business, Wells saw an opportunity to make more money in the pork-packing business, and in 1839 was one of four packers who packed a total of 5,000 hogs. By 1846, the four packers -- Edward Wells; Nathaniel Pease; Whitney & Co.; Holmes, Brown & Co. -- were packing 10,000 hogs a year.

In 1835, the state of Louisiana passed an act intended to standardize the packing industry and gave instructions in what each barrel of pork must contain. For instance, a "MESS PORK barrel must be composed of the choicest sides of well-fattened hogs -- neither flanks, tailpieces or any part of the shoulder will be admitted. A PRIME PORK barrel must have three shoulders with the shanks, cut off at the knee joint, one head and a half, divested of ears, snouts, and brains. In addition to the balance to be made up of sides, necks and tailpieces, and a sufficiency of side pieces to form the first and last layer in the barrel. A CARGO PORK barrel may be made of any parts of the hog that can be considered merchantable pork, with not more than four shoulders and two heads in a barrel…."

The act also stated that "not less than one bushel of coarse salt shall be put in each barrel of beef and pork besides pickle, to be made with as much salt as the water will hold in solutions."

The Quincy pork packers had to adhere to this 1835 act if they were to ship pork barrels to New Orleans.

On May 8, 1835, a barrel of mess pork was bringing $11, while a barrel of prime pork was bringing $9, and a barrel of cargo pork paid $7.

Early farmers in the area found that the soils in the county and around Quincy raised excellent corn. Corn, however, was not a commodity easily sold or shipped. Rather than selling their corn, farmers fed the corn to their hogs, which could more easily be driven and sold. It was found that to fatten a hog correctly took one bushel of corn for each 8 to 10 pounds of gain. As can be seen, the production of pork in any given year is largely dependent on the yield of corn, which, in turn, is dependent on the weather.

In 1835, farmers were raising hogs on farms and in woods east of Eighth and Hampshire streets, north of Broadway, and beyond three blocks south of Maine Street, as well as farther out in the county.

Pork packing from 1835 to 1866 became a thriving business in Quincy. By 1866, 14 pork packers were listed in the city directory. These companies were housed in buildings primarily along Front Street along its north extension and south to Washington Street, and on the bluff along Second and Third streets.

During the 1862-63 pork-packing season, Quincy was seventh on the list of cities in the West for the number of hogs slaughtered. That winter, Quincy's packing plants slaughtered and packed 100,000 hogs. Most of those hogs would have been driven or herded on foot from the farms to the packing houses along the river.

The packing companies sold the processed hogs as pickled pork in mess, prime and cargo barrels. Also, bacon, lard, sugar hams, smoked hams and sausage were processed.

Pork packing was seasonal and occurred only in the colder months of the year, mainly from late November to February. However, Herman Witte opened a packing house in May 1869 and announced that he was prepared to kill and pack pork during the summer season. He would be packing his kills in ice procured from the bay.

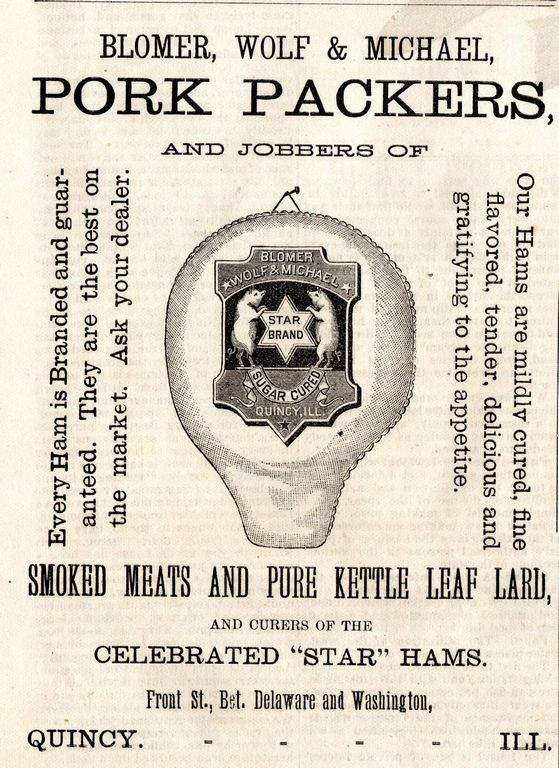

By 1885-86 only four packing houses remained in business: Blomer, Wolf & Michael; H. Behrensmeyer & Co.; S. Farlow & Co.; and Clemence Kathman.

The company of Blomer, Wolf & Michael was established in 1882 on Front Street, between Delaware and Washington streets, and continued until 1890, at which time Wolf left the company. Blomer and Michaels continued the packing business until their packing house burned Feb. 15, 1913. The fire signaled the end of pork packing in Quincy.

Because of the availability of railroads, refrigeration, canning processes, freezing capabilities, motor trucks and improved highways, the smaller town pork-packing plants closed. Large packing houses such as Armor, Cudahy, Swift and Wilson from the large cities brought their products to Quincy via rail and trucks, and the local plants could not compete.

Don McKinley is a retired Quincy elementary school principal. Since retirement he has created a 1930s agricultural museum, written a book about his early farm years and has had several magazine articles published about items in his museum.

Sources:

"A New Enterprise," Quincy Whig, May 15, 1869, Page 3.

"Adams County," Illinois Bounty Land Register, July 3, 1835, Page 1.

"An Unwelcome Item," Quincy Daily Journal, Jan. 4, 1892, Page 7.

"Announcement," Quincy Daily Journal, Dec. 16, 1890, Page 6.

Asbury, Henry, Reminiscences of Quincy, Illinois, Quincy, Ill., D. Wilcox & Sons, 1882.

"Beef and Pork," Illinois Bounty Land Register, April 17, 1835, Page 2.

Carlson, Theodore L., the Illinois Military Tract, New York: Arno Press, 1979, Page 123.

"Cash for Pork and Beef, Illinois Bounty Land Register, Nov. 6, 1835, Page 3.

Collins, William H., and Cicero F. Perry, Past & Present of the City of Quincy and Adams County, Ill., Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1905, Page 22.

"DIRECTIONS taken….," Illinois Bounty Land Register, July 3, 1835, Page 2.

"Fire Destroys Packing Plant," The Quincy Daily Herald. Feb. 15, 1913, Page 1.

Gould, "Pork Packers," Quincy City Directory, 1885-86, Pages 464-465.

"Pork Packing in Quincy," Quincy Whig, Feb. 12, 1870, Page 3.

"Pork Packing in the West," Quincy Daily Whig, April 21, 1863, Page 3.

"Quincy Prices Current," Illinois Bounty Land Register, May 8, 1835, Page 3.

Roots, "Pork Packers," Quincy City Directory, 1866, Pages 213-214.

"SH FOR PORK." Illinois Bounty Land Register, Oct. 23, 1835, Page 3.

"The Herald," Quincy Daily Herald, May 23, 1881, Page 4.

"The Pork Season," Quincy Whig, Nov. 28, 1868, Page 3.

Wilcox, David F., ed., Quincy and Adams County History and Representative Men, Vol. 2. New York: Lewis Publishing Co., 1919.