A Quincy lawyer was last to meet with Lincoln

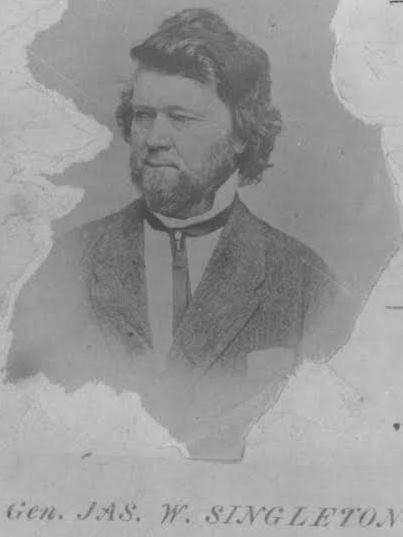

James Washington Singleton of Quincy was one of Abraham Lincoln's strongest Northern opponents during the Civil War, even opposing his re-election in 1864. Yet, while they differed on principles and political issues throughout the war, with its end in sight and the president considering reconstruction of the Union, Lincoln had faith that Singleton was as well suited as any man in the nation to help restore peace and reunite the South.

"If there is anybody in the country who can have any influence on those people (of the South), and bring about any good," Lincoln told Singleton, "you are the man.... You have been as much their friend as it was possible for you to be and yet be loyal to the government under which you live."

Lincoln had authorized the Quincy lawyer four or five times to meet with Confederate leaders, including President Jefferson Davis, to seek a way toward peace. The Virginia-born Singleton, whose brother was a member of the Confederate Congress, had easy access to the rebels at Richmond.

One of Lincoln's last official visits in the White House before his assassination on April 14, 1865, was with Singleton. The president had been thinking as early as 1862 about ways to reunify the nation after the Civil War. By the beginning of 1865, his reconstruction efforts had begun in Louisiana, Tennessee and Arkansas. He considered Virginia the most important field in the work of reconstruction, and he tapped Singleton to do it.

Lincoln and Singleton met for half an hour. Lincoln signed a pass for Singleton to cross Union lines into Richmond, the Confederate capital, and then interrupted the meeting. Time forced him to leave. He had an engagement with wife Mary that evening to see a play, "Our American Cousin," a comedy, at Ford's Theatre.

Born in Paxton, Va., in 1811, Singleton was 17 when he left his home for Kentucky. The father of Singleton's first wife, Ann, was a doctor and taught him medicine. Unable to develop his practice, Singleton was persuaded by a cousin in 1834 to move to Mount Sterling, Ill. He did, studied law there, and in 1848 was admitted to the bar. By that time, he twice had been married and had one son. All had died by 1841. He married Parthenia McDannald in 1844, and the couple had a daughter and son.

The Mormon Wars in Western Illinois drew Singleton into militia duty. When Mormon Prophet Joseph Smith was killed at the Carthage Jail on June 22, 1844, Gov. Thomas Ford ordered Capt. Singleton and 60 militia members to Carthage to help keep the peace. They returned home July 2, but violence erupted again. Congressman Stephen A. Douglas and church leaders negotiated a settlement, but when not all had left by the fall of 1846, some 1,500 anti-Mormons were poised to attack the Mormon city of Nauvoo.

Singleton, who led the force, negotiated a final departure. His officers refused to accept it, however, and he resigned his command. Peace came only after ammunition ran out.

Singleton and family moved to Quincy at the end of his second term as state representative in 1854. In 1862 he acquired a 640-acre farm, which he named Boscobel, northeast of Quincy. In addition to agricultural interests, Singleton became involved in railroads. He became president of the Quincy and Toledo and the Quincy, Alton, and St. Louis lines.

The death of their party in 1854 separated Whigs Lincoln and Singleton, who had campaigned together for the presidential candidacies of Henry Clay and Zachary Taylor. Lincoln gravitated to the new anti-slavery Republican Party. Singleton joined the Democrats.

At the outset of the Civil War, Singleton led Illinois' Peace Democrats. He turned down an appointment by Gov. Richard Yates in 1861 to lead 10 volunteer cavalry companies. He also disputed Lincoln's handling of the war at its beginning, considering the president's actions arbitrary and unconstitutional.

Although he opposed Lincoln's re-election in 1864, Singleton refused to support the candidacy of Lincoln's Democratic opponent Gen. George B. McClellan, whom he considered aristocratic.

Despite the antagonisms, Lincoln, at the request of Singleton and Quincyans Orville Browning and Congressman William Richardson in 1863, lifted his embargo on trade with the South so tobacco could flow from Missouri to Quincy's tobacco manufacturing companies.

In the fall of 1864, Singleton, Browning and three other men devised a deal to buy cotton and tobacco in Virginia. Lincoln personally supported the plan. The Confederacy's currency was virtually worthless, and Lincoln believed U.S. greenbacks could provide some needed relief to the increasingly destitute region.

In Richmond in mid-January 1865, Singleton bought $7 million worth of cotton and tobacco. Lincoln agreed to help Singleton's group get the products into the United States, but he left the decision on moving it through Southern lines to Gen. Ulysses Grant.

Without knowing the design of the plan, Grant accused Singleton of greed and sacrificing "every interest of the country to succeed." The Confederates on leaving Richmond set fire to the building where the cotton and tobacco were warehoused. The Singleton group lost its investment.

Although Lincoln, in the words of historian Michael Burlingame, was " ‘not carried away' by Singleton's ‘suggestions as to the best way to restore harmony between the two ‘nations,' " he was encouraged by Singleton's report of his trip South that "fair compensation" for slaves and "other liberal terms" might persuade the Confederates to stop fighting. Singleton appreciated Lincoln's trust. He wrote to his wife: "My intercourse with (Lincoln) for the past six months has been so free, frequent, and confidential that I was fully advised of all his plans, and thoroughly persuaded by the honesty of his heart and wisdom of his humane intentions."

After the war, his neighbors twice elected Singleton to Congress. He spent most of his later years managing his estate and railroads. He died at the Baltimore home of his daughter Lillie on April 4, 1892.

Reg Ankrom is a former executive director of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County and a local historian. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources:

Peter J. Barry, General James W. Singleton: Lincoln's Mysterious Copperhead Ally. Mahomet, Ill., Mayhaven Publishing Co., 2011.

Jodi L. Bennett, "James Washington Singleton Papers, 1770-1995." Old Dominion University.

Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Vol. 2. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

James B. Conroy, Our One Common Country: Abraham Lincoln and the Hampton Roads Peace Conference of 1865. Guilford, Conn.: Lyons Press, 2014.

Dave Dulaney, "A Wedding at Boscobel," Quincy Herald-Whig, March 10, 2013.

John Hay, Inside Lincoln's White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay. Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, eds. Carbondale, Ill.: Southern Illinois University Press, 1979.

Allen Nevins, "Lincoln's Plan for Reunion," Abraham Lincoln Association Papers. Springfield: Abraham Lincoln Association, 1939.

"Peace and Unconditional Surrender," the Lehrman Institute, at http://lincolnandchurchill.org/peace-unconditional-surrender/

"Singleton, James Washington, (1811-1892)," at http://bioguide.congress.govv/scripts/biodislay.pl?index=s000444