Adams County men fight at the Battle of Shiloh

Sunday, April 6, 1862, had been a day in hell for the Adams County men of the 50th Infantry Illinois Volunteers — Union soldiers for little more than seven months. They had been under heavy fire on that first day of the Battle of Shiloh. Casualties were staggering. The men of the 50th knew the din of fire. They had been with pit bull Major Gen. Ulysses Grant to pull down the Confederate flag at Fort Henry on Feb. 8, and they were at the front of the Union ’s attack that took the enemy’s works at Fort Donelson in three days of pitched battle a week later.

The men of the 50th had seen the horrors of war. Three soldiers died and many more were wounded in the two battles.

“It was an awful sight to one like myself, who never saw the like before, to see dead strewed all over the ground — men without heads and arms,” wrote Company K’s 28-year-old Timothy D. McGillicuddy, who had come from Hannibal, Mo., to join the 50th. Much more of the same was to come. The two-day battle in April in southwestern Tennessee took its name from the small church near the center of the battlefield. Its name, Shiloh, haunted those who fought there. In Hebrew it meant “place of peace.” Now it meant anything but — casualties of the North and South at this place numbered more than 23,000. More than a hundred were men of the 50th Illinois. Planning to attack the Confederate transportation hub at Corinth, Miss., 20 miles south, Union generals had been amassing forces at Pittsburgh Landing on the Tennessee River just northeast of the church.

With the first sunlight shimmering on the Tennessee River shortly after 5 a.m. on April 6, a patrol from Gen. Benjamin M. Prentiss’ Sixth Division ran headlong into an advance picket of the 3rd Mississippi Infantry. The rebel Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston had decided to strike before Grant could unite his army with Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s force, then on its way down the Tennessee River. Johnston’s plan was to insert his forces between Grant’s organizing army and the Union forces arriving at Pittsburgh Landing. With little coordination among them, federal units found themselves continually outflanked and pushed back by the rebels. On the Union’s left flank, where the thick of the enemy attacked, Prentiss’ untested regiments resisted the onslaught but were forced back repeatedly until they reached a deeply-rutted wagon path called the “Sunken Road.” Grant ordered Prentiss to hold the position “at all hazards.” So intensive was the exchange of fire, Prentiss’ men christened it “The Hornet’s Nest.”

Elsewhere, the Adams County-formed 50th Illinois was ordered to aid Illinois Col. David Stuart’s Second Brigade on the far east side of the Union line, near the river, and which now was under heavy attack. Scouts Michael Ward and Martin Kiser, both privates from Quincy, hurried back to Company C, which was crouched in a ravine, to warn of a large line of advancing rebels snaking toward them.

First Lt. Theodore Letton, a Quincy music teacher before the war, saw the Confederate flag, then hundreds of rebels, their heads bobbing and rising above the west horizon just ahead. Letton ordered his men to open fire. At the same instant, the 50th felt the heat of fire from the rear. The enemy line was clamped around them, extending past the south end of the ravine, which put the rebels behind the men of Company C.

“To say that I was surprised and horrified would fall far short of expressing my feelings at that moment,” Letton wrote in his reminiscence of the battle. “I felt certain the whole company would be annihilated.”

Letton

ordered his men to pull back, take positions behind the trees, fire, retreat to

the next tree line back, reload and repeat the tactic.

“We retreated probably a mile, and I am confi dent the enemy

suffered a great deal more than we did in that running fight,” Letton wrote.

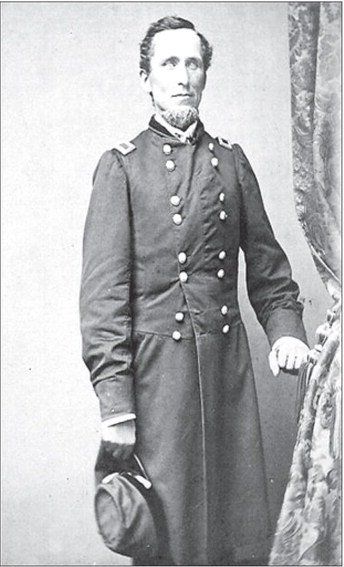

But the 50th suffered plenty. Seventy-nine men went down in the first 15 minutes. A rebel musket ball blew Colonel Bane from his saddle, shattering the bone in his right arm above the elbow. The projectile ripped into Bane’s side, fracturing two ribs and lodging in his chest. Doctors said the wounds were mortal. His brother Garner, a surgeon from Liberty, however, saved Col. Bane’s life by amputating the arm.

Meanwhile, Prentiss’ men withstood repeated Confederate attempts to overrun them and were buoyed by reinforcements from Gen. W.H.L. Wallace’s Second Division on the right and Illinois Gen. Stephen Hurlbut’s Fourth Division on the left.

By mid-afternoon, however, rebels were ripping Hurlbut’s unit apart and heavy artillery fire forced Wallace to fall back. Wallace himself did not make it. A musket ball crushed his skull and exited through one eye. In the exchange, Confederates suffered an even greater loss. Gen. Johnston, one of the South’s most important generals and a favorite of rebel President Jefferson Davis, was mortally wounded.

Now at the salient point of the battle, Prentiss and his men held at the Sunken Road under the severest southern fire of the day. Shortly before 6 p.m., nearly 12 hours after Prentiss’ men first engaged the enemy, the Confederates surrounded the Sixth Division. Prentiss surrendered his exhausted force to Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, whose attack on Fort Sumter a year earlier had started the Civil War. With that act, which saved the lives of 2,200 men, Gen. Prentiss had “lost everything but honor,” said the official war record. His division’s stand bought Gen. Grant the time he needed to organize his army for victory the next day.

For hundreds of young men in Prentiss’ Sixth and Bane’s 50th, who had stubbornly contested every inch of ground at Shiloh on April 6, 1862, the Civil War was over.

Reg Ankrom is executive director of the Historical Society. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

S ources

Costigan, David. "Once Upon a Time in Quincy: Civil War Generals." Quincy Herald-Whig, October 28, 2011. At http://www.adamscohistory.org/Prentiss__Brigadier_General_Benjamin.pdf

Hicken, Victor. Illinois in the Civil War. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1966.

Hubert, Charles F. History of the Fiftieth Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry in the War of the Union. Kansas City, Missouri: Western Veteran Publishing Company, 1894. Collection, Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

"Illinois Civil War Detail Report." Illinois Secretary of State. At http://www.ilsos.gov/isaveterans/civilmustersrch.jsp

"List of Quincy Soldiers Who have died in the service of their county in the war of the Great Rebellion," The Directory; History and Statistics of the City of Quincy for the Years 1865-1865. Compiled by S. B. Wyckoff. Quincy, ILL: Steam Press of the Whig and Republican, 1864. Collection, Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

"Maps of Shiloh, Tennessee, 1862: Battle of Shiloh, TN, April 6, 1862, Day One" Civil War Trust. http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/shiloh/maps/shilohmap.html

Prentiss, Brig. Gen. B. M. "Report of Brig. Gen. B. M. Prentiss, U. S. Army, commanding Sixth Division, Quincy, Ill., November 17, 1862," War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Vol. X. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1884. Collection, Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

"50th Illinois Infantry Regiment History," Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Illinois, Volume III Containing Reports for the Years 1861-1866. Revised by Brigadier General J. N. Reece, Adjutant General. Springfield, Illinois: Phillips Bros., State Printers, 1901. At http://civilwar.ilgenweb.net/reg_html/050_reg.html