Historical Society's dolls reflect their ages

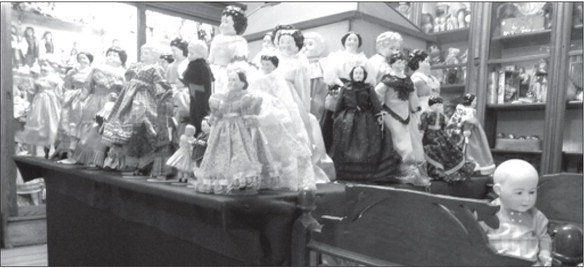

More than pretty

playthings, the hundreds of dolls on display in the History Museum of the

Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County reflect the art, materials,

tastes and social mores from the 1840s to the 1980s.

Most are from the collection of Helen Breuer, a Quincy school

teacher who bequeathed her collection to the society in 1983, but many come

from families and smaller collections. They represent dolls that young girls

would have coddled and carried in Quincy and Adams County from founding days.

One of the earliest dolls in the collection belonged to

Eleanor Cannell, who later married Michael Piggott, a prominent Quincyan.

Cannell, then 2, came to Quincy with her family in 1836 from Buffalo, N.Y. For

two years the family lived in the log cabin John Wood built at today’s Front

and Delaware streets and moved in 1838 to another log cabin at 11th and Cherry.

Cannell’s aunt gave her this primitive doll sometime after 1838. The doll has a

carved wooden head with simply painted features and hair. Her wooden arms and

legs are attached to a hand-stitched leather body.

Her pink hand-sewn dress

appears to be original.

By the mid-19th century, the small figures little girls

cherished were made of a very different material. Artisans in Germany began

using porcelain to produce shoulder-head dolls. The head, neck and shoulders

were molded in a single piece and attached to cloth or leather bodies.

Many had

stark white faces and black hair. The Historical Society’s collection includes

many of these china-head dolls, which usually are classified by their hair

style. The more desirable have hairdos named for noted women or characters,

like the Jenny Lind and Dolly Madison dolls in this collection.

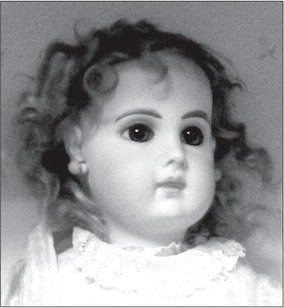

The hard, cold shiny white faces of the porcelain dolls gave way in the late 19th century to a new medium for doll making. Bisque porcelain would find immediate favor with children and parents alike. Unlike the coldness of the china surfaces, bisque has a softer matte finish and natural skin tones that are fired into the material. With the addition of glass eyes, these dolls were desired by little girls, who might see something of themselves reflected in them.

Several of the gems in this collection came from France, whose manufacturers produced some of the world’s most desirable dolls. A French doll maker known for its finest quality dolls was the firm of Jumeau, whose doll production rose to prominence in the last quarter of the 19th century. Under the direction of Emile Jumeau, the factory began producing “bebes” or child dolls. In this collection, one of the loveliest and finer doll heads bears the prized mark, “Depose E9J.” The initials designate the manufacturer, Emile Jumeau, and the number the size of the doll. The incised mark would date this head to the early 1880s.

Jumeau dolls are best known for their incredible eyes. A booklet published in 1885, “The Notice on the Making of Bebe Jumeau,” includes an illuminating chapter describing the skill and artistry required to make the eyes. Emile Jumeau trained orphaned girls as apprentices to sit before gas furnaces and, using foot pedals to regulate heat and air, form and thread layers of molten glass into spheres. Their talents gave the Jumeau eye its moist, life-like softness and depth. While no specific age is given for these young artists in glass, one cannot help but compare these diligent workers with the children who would enjoy endless days playing carelessly with their creations.

Most dolls that flowed into this country in the late 1800s were from the Thuringia region of central Germany. Firms specialized in the more common “dolly faced” bisque dolls. Most prolific of these firms was Armand Marseilles, and several dolls in the HSQAC collection were made in his factories. These have stylized child faces with glass sleep eyes that close when the doll is laid down. Open mouths display a row of teeth.

Two other German firms were Kestner and Simon Halbig, whose dolls rivaled the French with some of their unique “character faces.” Unlike the dolly faces, these dolls have a portraitlike quality in their faces. One in this collection from 1909 and especially rare is a Simon Halbig mold 1279. An impish turned up nose, large wide-set eyes, and a slight overbite separate her from the more common molds.

By the 1920s, dolls made of composition materials gradually replaced bisque headed dolls. Made of pressed wood pulp, composition finally allowed American firms to be competitive in the doll market. This collection has several examples of the composition doll from the American firm Effanbee. Their most popular dolls were in the “Patsy Family.” One Historical Society doll is a nine-inch Patsyette in very nice condition, sporting her factory-original outfit and even an original wrist tag that calls her a “lovable imp.” Her perky short dress and bobbed hair under her cloche-style hat reflect the fashions of the late 1920s and 1930s.

After World War II, the doll-making industry embraced the wonderful new medium of plastic, and America was finally the center of the industry. One of the best examples of hard plastic dolls in the Society’s collection is the “Mary Hartline” doll. Manufactured by the Ideal Toy Company, she is dressed as a drum majorette and accompanied another technological advance — television. Mary Hartline was a featured performer on “Super Circus,” a Saturday morning television show for children. Her thick blond hair, short red dress and fancy white boots put her at the top of many little girls’ wish lists.

Baby boomers were growing up, and so were their dolls. In 1959 toy maker Mattel took a risqué German comic strip character named Lilli and transformed her into the iconic American Barbie doll. Children clamored for the tall, sleek, full-bosomed doll made of rigid vinyl with rooted hair pulled into a tight pony tail. Examples in this collection are minty and in original boxes— original boxes increase a doll’s value—and include not only four Barbies but also boyfriend Ken, little sister Skipper and Skipper’s friend Ricky.

Only a few dolls from this massive collection have been mentioned. Yet from the rustic little doll that survived life in a Quincy log cabin in the 1840s to a Coleco Cabbage Patch doll from 1985, their faces command a place in history. The numbers and variety of the Historical Society’s collection are overwhelming. They line the walls patiently, as if, in the words of Eugene Field, “awaiting the touch of a little hand and the smile of a little face” to again be discovered and cherished by children of all ages.

Jane Ankrom is a graduate of the University of Kansas with a degree in art history. She has been a doll enthusiast and collector most of her life. In 2008 she helped evaluate the Historical Society’s doll collection.

Sources

Davies, Nina S. The Jumeau Doll Story. Grantsville, Maryland: Hobby House Press, 1969.

Deutsch, Stefanie. Barbie the First Thirty Years. Paducah, Kentucky: Schroeder Publishing Co. Inc., 1996.

Foulke, Jan. Sixteenth Blue Book – Dolls and Values. Grantsville, Maryland: Hobby House Press, 2003.

Husar, Edward. "Museums unite for ‘Discovery Weekend.'" Quincy Herald-Whig, November 2, 1984.

King, Constance E. Jumeau. West Chester, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 1983.

"Midnight Ends Life's Journey; Death of Mrs. Michael Piggott, of Pioneer Quincy Family." Quincy Daily Whig, March 27, 1909.

Moyer, Patsy. Doll Values. Paducah, Kentucky: Schroeder Publishing Co. Inc., 1997.

Richter, Lydia. China, Parian and Bisque German Dolls. Grantsville, Maryland: Hobby House Press Inc., 1993.

Schoonmaker, Patricia N. Patsy Doll Family Encyclopedia, Vol 1. Grantsville, Maryland: Hobby House Press, Inc., 1992, 1995.