Citizen Wood and his Woodland Cemetery

John Wood in 1846 was 48 years old when he began thinking about his own mortality. Wood had felt death's chill. By then all of his eight children had been born and three had died. His father Daniel, who had served in the Revolutionary War as a surgeon in Col. Aaron Burr's regiment, died in 1843.

Baby Emily died at the age of two in 1835, the year Wood began construction of a two-story Greek Revival mansion into which he moved his family from their two-story log cabin in 1837. Adah, 9, the Woods' fifth child, died in 1844. Henry, the seventh child and third son, died in 1842 at age three. The family's last child and fourth son James, who was 8, would die in 1850.

Some 60,000 souls rest at Woodland.

The first two decades of Wood's life in Quincy were a whirlwind of building: a city and county, a portfolio of real estate assets, a farm, and a dogged interest in politics, business and domiciles.

Lorenzo Bull was 14 when he arrived in Quincy. He saw Wood's stamp throughout the adolescent city.

"Wood was a very energetic, active young man," Bull recalled many years later, "always on the move, and who seemed to be everywhere, all over the town, all over his large farm, driving and pushing everything and everybody about him."

John Wood was, said Bull, a force of nature. He remembered that Wood's voice was loud and strong and his laugh exuberant and unrestrained, known by everyone in town. Bull said he asked a man one morning if he had seen Wood in town. The man answered he had not seen him but figured he had to be there.

"I heard him whisper," the man said.

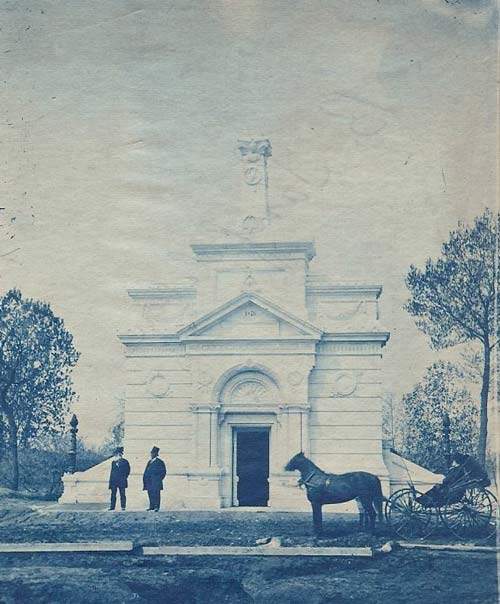

At the time he laid out the cemetery in 1846, Wood was mayor of the city he and Willard Keyes founded. A man who had much more to do in the years ahead--in business, charity and politics, Wood sought a place his community could memorialize its dead.

Hills and valleys rolled across the limestone bluff high over the Mississippi River at the place Wood chose for his cemetery. The terrain was just as he had found it nearly a quarter century earlier. Sentiment dictated the spot. Just north was the younger Wood's first possession here, a simple one-room, puncheon floored log cabin on the southeast corner of today's Front and Delaware Streets. It was the first of four homes Wood built in Quincy, each greater than the last, each symbols of Wood's widening wealth.

Within three years after Wood organized the cemetery, Asiatic cholera hit Quincy and killed some 400 area citizens, including former Quincy Mayor Enoch Conyers. Most of the victims were buried quickly in Woodland without permits in unmarked graves. When the city began construction of Jefferson Street between Front and Fifth Street on the north side of the cemetery, the bones of many cholera victims were exposed on the slope.

The War Department in 1900 ordered the removal of 390 bodies of soldiers from Woodland, a national military cemetery since 1861, to Graceland Cemetery after the hillside along Jefferson washed out once again, exposing remains of veterans whose rest had been pitifully disturbed by heavy rains.

There are at Woodland many graves of men who fought in the nation's wars. The body of Martin J. Hawkins, a Congressional Medal of Honor winner in the Civil War, is there. So is the body of James Dada Morgan, a brevetted Civil War major general beloved by his men for never asking them to do what he would not do himself. And the body of Capt. John M. Cyrus of Camp Point, who fought with the 50th Illinois Infantry, organized in Quincy, at the Battle of Shiloh, is there.

Several congressmen are buried there, including George Alburtus Anderson, Orville Hickman Browning, John Montgomery Glover, Isaac Newton Morris and William Alexander Richardson. Illinois Supreme Court Justice Onias Childs Skinner is buried there.

There, too, are many women of Quincy honored for their spirit of industry, benevolence and pioneering. Among them are Sarah Denman, founder of Blessing Hospital, the international women's study group Friends in Council and the Civil War's benevolent Needle Pickets; Abby Fox Rooney, the first woman licensed to practice medicine in Illinois; and Candace Reed, a business woman whose photography is prized among collectors. Alongside her husband, U.S. Sen. Orville Browning, is Eliza Caldwell Browning, particularly noted for her 28-year friendship with Abraham Lincoln.

The humble rest near the honored. In his diary on Sept. 7, 1858, Browning wrote, "Another bright, warm, beautiful day. Old Aunt Polly, our colored woman, died this A M. between 12 & 1 O'clock, and was buried in Woodland Cemetery at 4 P. M."

Wood planted a white oak tree at the center of the cemetery. It was the site of the lot that he chose for his own final resting place. Several members of his family are buried within 15 feet of the tree, including Wood's father Daniel, whose body John Wood brought in 1860 from its Cayuga County, N.Y., grave to Quincy. Some family members believe that Wood had only his father's head moved -- in a hatbox -- to be buried in Woodland. The Historical Society's first account reports "the body" was brought to Quincy, which some wordsmiths have twisted to mean that the body is here and the head remains in New York.

Cemeteries were not only places of repose for the deceased. They were considered places of reflection and meditation for those who wished to visit. Wood was impressed with the Victorian period that began in 1837 and brought with it artistic stylizations that were applied to tombstones and monuments to say something about the deceased.

On either side of the monument over the grave of Gottlieb Arning are an anvil and a quenching pot, representing the life's work of the blacksmith who arrived here from Germany in 1845. A sleeping child and lamb represent 10 of the 14 children of the William King family who died before they reached the age of 10.

Wood, who installed himself as the cemetery's caretaker for the next 35 years of his life, spent considerable time there, sitting in the office in a woven-reed chair owned today by the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County. As it is today, the cemetery was a quiet place. Wood considered it a sacred place. In a "Notice to the Public" in the Quincy Daily Whig of May 27, 1854, he asked that visitors respect the sanctity of the cemetery, that they not pick the shrubs and flowers from around the graves or hitch their horses to growing trees or take sod from the burial places.

At 11:15 a.m. June 4, 1880, Wood passed into the unknown "crowned with the honors of a long and eventful life," as the Daily Whig put it. The city was draped in black. Businesses and school closed. Thousands lined the route of procession.

Lorenzo Bull, now a scion of business himself, was one of 16 pallbearers who escorted the body from the Congregational Church to the grave beneath the shade of the white oak tree at the heart of Woodland Cemetery.

John Wood's body was returned to the earth at the place he had chosen. Over his grave was a simple monument, a thin sculpture on its face as Wood had directed. It was his one-room log cabin, symbol of a humble life. The simple stone, reflecting the way Wood wanted to be remembered, was stolen from his grave early in the next century.

Reg Ankrom is executive director of the Historical Society. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources

Browning, Orville H. The Diary of Orville Hickman Browning, Vol 1. Edited by Theodore Calvin Pease . Springfield: Illinois State Historical Society, 1925.

Bull, Lorenzo. "Personel Recollections of Quincy and Its Earliest Settlers as I Knew Them in 1833." Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Historical Society of Quincy, 1903 of Lorenzo Bull," May 1, 1903. MS File 920, Bull Lorenzo, Historical Soceity of Quincy and Adams County

Collins, William H. and Cicero F. Perry. Past and Present of the City of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois. Chicago: The S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1905.

"Dead: Death of Ex-Governor John Wood in this City." The Quincy Daily Whig, June 10, 1880.

The History of Adams County, Illinois. Chicago: Murray, Williamson & Phelps, 1879.

Landrum, Carl. "The Story of Woodland Cemetery." The Quincy Herald-Whig, April 6, 1980.

"To the Public," The Quincy Daily Whig, May 27, 1854.

"Woodland Cemetery, Quincy, Illinois" Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, 2005