Two from Quincy sought U.S. Senate seat

It would not be unusual for two aldermanic candidates to live four blocks from each other. If two mayoral contenders lived within a few blocks, it might pose an interesting contest between contenders from the same part of town. Rarely would state legislative contenders be from the same town in their district (outside of Chicago).

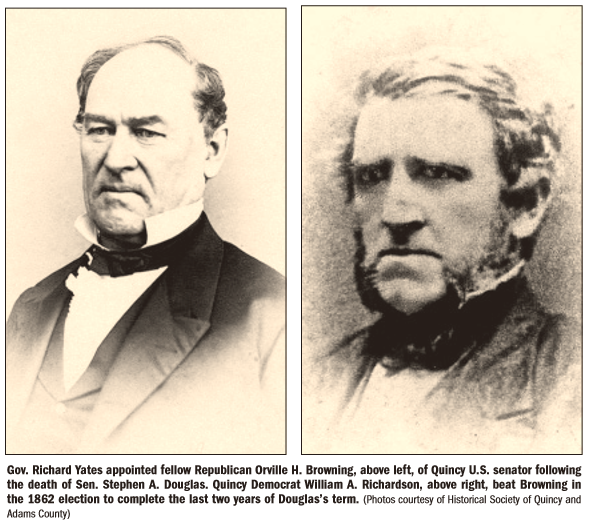

Those facts in political science -- about where opponents for the same office live -- made the election of Illinois' U.S. senator in 1862 especially unusual. The two candidates for the U.S. Senate that year lived only four blocks from each other in Quincy. Incumbent Republican Sen. Orville Hickman Browning lived in an imposing mansion at Seventh and Hampshire. Browning's Democratic opponent, Congressman William Alexander Richardson, lived in a beautiful home at Fourth and Broadway. The Senate nominees, whose duties were to serve all of Illinois, were both from Quincy. It was a sure sign that this westernmost Illinois city played a major role in mid-19th century state politics.

Gov. Richard Yates had appointed Browning to fill the vacancy created by the death of Democratic Sen. Stephen A. Douglas on June 3, 1861. Yates's surprising appointment of the Republican Browning to succeed the Democrat Douglas guaranteed a spirited election contest in 1862.

Browning was a prominent lawyer and close friend of President Abraham Lincoln. Their relationship went back to the days when they were young legislators in the Illinois General Assembly in the 1830s. Browning and his wife, Eliza, would often host the bachelor Lincoln to dinners during the legislative sessions. Their friendship, correspondence and political alliances continued over the course of the next three decades. Lincoln stayed in the Browning home after his debate in Quincy on Oct. 13, 1858, when he challenged Douglas for his U.S. Senate seat. Considered the leading trial attorney of the day from this area, Browning was in Carthage in the middle of a trial on debate day and missed what some local historians call the most important day in Quincy's history.

The senatorial election in 1862 was actually the fourth time Browning and Richardson had faced each other as political rivals. With state Rep. Lincoln inexplicably voting for him, Richardson beat Browning for state's attorney in 1834. Twice they had run against each other for the House of Representatives in the United States Congress. Richardson won both races, which were characterized as high-minded and honorably conducted.

During his brief tenure in the U. S. Senate, Browning had more than 90 documented meetings with President Lincoln. He would often accompany the president on his trips to the cottage at the Soldier's Home on the outskirts of Washington, which Lincoln used as a sort of Camp David retreat. When the Lincolns' son Willie died in February 1862, the Lincolns asked Orville and Eliza Browning to move into the White House, then referred to as the Executive Mansion, for 10 days to comfort and support the grieving first family. Lincoln often consulted Browning on important issues, including the content and timing of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Congressman Richardson was a powerful member of the U. S. House of Representatives. He was a protégé of Stephen Douglas, himself a former Quincy resident, and as Douglas had been, was chairman of the House Committee on the Territories. This was the great period of national expansion, and Douglas and Richardson were responsible for organizing most of the territories and states of the West.

Richardson was without a doubt one of the most prominent statesman ever to represent Western Illinois. He served in the state Senate when living in Rushville and went on to be chosen speaker of the House in the Illinois General Assembly. He moved to Quincy because of its emergence as the center of commerce and industry. It was from Quincy that he was twice elected to the United States House of Representatives. President James Buchanan appointed him governor of the Nebraska Territory -- Richardson County, Neb., is named for him, where he served for 10 months in 1858.

In 1862 senators were not selected by the direct vote of the electorate, but by the legislature. As a result, party performance statewide was crucial. Although a savvy and seasoned political player, Lincoln took a different view of the 1862 election. He believed the election would rise above partisanship and appeals to party loyalty. He based this on the national crisis of Civil War. He reasoned that this situation was unprecedented and, accordingly, the union states would set aside appeals to party and transcend political considerations in the elections.

The president's friend and supporter John Sherman, brother of Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, warned Lincoln that his reasoning was flawed. The Democrats in Illinois, he said, were organizing and campaigning on a partisan basis. Sherman advised Lincoln to respond and defend the Republican record. Sherman was one of the leading Republican political figures of the mid-19th century and came close to being nominated for president while a senator from Ohio. He lost after a dead-locked convention turned to James Garfield in a compromise.

Unfortunately for Browning, Lincoln chose to ignore Sherman's advice, and Richardson defeated Browning. Voter turnout always decreases in off-year elections, but historian Mark Neely has pointed out that the number of voters who stayed home in the 1862 election was much greater. Democratic drop off from the 1860 presidential elections was 15 percent in Illinois. Republican turnout was down 30 percent.

As a result, the relatively new Republican Party sustained losses in the Illinois state Senate, whose members would join representatives in the Illinois House to elect the next U.S. senator. Accordingly, Browning lacked the requisite support in the legislature to remain in office. The prosecution of the war had gone badly, and had it not been for a recent turn around, the results might have been worse. Many considered the poor showing to be a referendum on Lincoln's performance in office over his first 18 months and, particularly, his announcement on Sept. 22 of the Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln reportedly explained to Wisconsin's Carl Schurz that Republican losses had resulted from Republicans going off to fight for the Union while Democrats stayed home to play politics.

Orville Browning went on to serve in President Andrew Johnson's cabinet as secretary of the interior. He then established a successful law practice in Washington, D.C. On April 9, 1869, Browning returned permanently to Quincy, where he died Aug. 10, 1881.

William Richardson ably represented our state in the U.S. Senate. After serving out the remainder of Douglas's term, he returned to Quincy where he practiced law. When Richardson died Dec. 27, 1875, Browning gave the eulogy at his funeral.

Both of Illinois' Civil War-era U.S. senators from Quincy are buried within 100 yards of each other in Woodland Cemetery.

Browning and Richardson having done their part, Quincy remained a major force in Illinois government as civic, cultural, education and business associations grew in the late 19th century.

Chuck Scholz serves as secretary to the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation and is on the Looking for Lincoln Board. He was chairman of Quincy's Lincoln Bicentennial Commission. Scholz, three-term mayor of Quincy, practices law with his son, Jacob Scholz, at Scholz and Scholz and is a member of the Illinois State Board of Elections.

Sources:

Donald, David Herbert. We Are Lincoln Men: Abraham Lincoln and His Friends. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2003.

Holt, Robert D. "The Political Career of William A. Richardson." Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. Springfield: Illinois State Historical Society, 1993.

Neely, Mark. "Lincoln Anticipates Emancipation." Lecture to Annual Meeting of the Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation, Washington, D.C., Sept. 16, 2012.