City's architecture has sense of identity

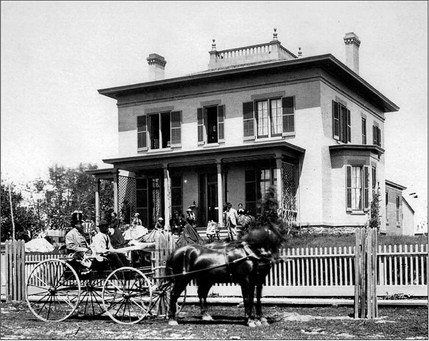

As people walk up and down the streets of Quincy, they can see the echoes of the past in the buildings that surround them. The residential areas of Quincy provide examples of every style of Victorian home, from Queen Anne to Italianate Revival styles.

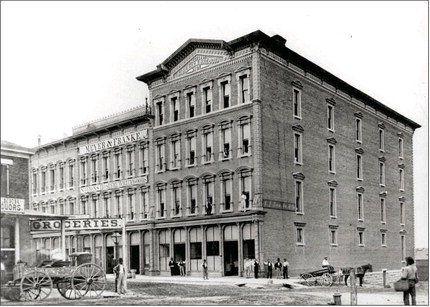

In addition to the residential areas, downtown Quincy retains many buildings from the mid- to late-19th century. In both the residential and commercial sections, Quincy stands as an example of how a community's values are reflected in its architecture.

At a time when Quincyans held the power to decide what kind of environment they wished to create for the city, they decided to build using Victorian trends. Not only did they use the Victorian architecture and building techniques for their homes, but they also used it in their commercial buildings. Quincy exemplifies how a city can follow a national trend but still maintain its own sense of identity. When other cities placed facades on the top of their businesses, Quincy architects held true to Victorian style but they used the upper floors for residences because of their dedication to not waste space. This mixture of fashion and function sets Quincy apart from other cities that boomed in the Victorian age.

The Victorian type of architecture seemed to best suit the people of Quincy because of its emphasis on the home and the family. The tree-lined streets of Quincy lent themselves perfectly to the inviting architecture of the times. The rise of industry and individual German craftsmanship allowed the wooden frames of Victorian homes to sprout up all over the city.

Industrialization allowed Quincy to boom economically and socially. Newer and cheaper materials permitted the middle class to imitate styles they saw the upper class using. Early 19th century styles, like Beaux-Arts, did not fit the lifestyle of Quincy's citizens. Quincy, as a small town, did not utilize the grander style of the Greek or Roman architecture because it did not match the gentler and quieter demeanor of the city. The John Wood Mansion is a rare example of Greek architecture in Quincy. The Art Deco architectural movement arose in 1918, but during that time, Quincy had declined in economic power because river transportation faced stiff competition from the new railroad lines. Therefore, only a few buildings in the downtown area, such as the State Theatre, portray the geometric design of Art Deco.

Most of the downtown buildings do not serve the same purposes they once did. For example, the building at Third and Hampshire that is now home to the restaurant Tiramisu used to house a "dry goods and notions" store. There are buildings, though, that maintain the same type of business as they did in the 1800s. For instance, the Fletcher's Tremont Hotel located at Sixth and Hampshire in the Victorian Era is now the Hotel Quincy. The Victorian past can be seen in other cities, but what sets Quincy apart is its dedication to maintaining as much of its original architecture as possible while keeping up with modern times.

The history and values of any city or people can be seen in the buildings that stand the test of time. The Pyramids of Giza, the Parthenon, the Hagia Sophia; all these great buildings are still being talked about and studied to this day. Architectural historians not only study the materials and building techniques used to construct these structures, but they also study the people and the times in which the monuments were built. The Hagia Sophia started as a Christian church, then became an Islamic mosque, and now serves as a museum for visitors. Historians discuss residential buildings like the Breakers, built for the Vanderbilt family, and the local John Wood Mansion. Their themes range from what functions rooms filled, to who lived in the houses, and where and when the houses were built.

When people live in times of prosperity and can choose for themselves what buildings they want, their choices reflect the values they hold in esteem at that time. When Chicago burned to the ground, the city invited many different architects to help rebuild because they understood that they could rebuild the city into something new and fascinating, now the city is revered as a site of architectural progressiveness.

Quincy is no different from world heritage sites in that people are still studying and preserving the architecture of Quincy's history. Organizations like Quincy Preserves, the Quincy Museum, and the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County work to spread the word about the hidden gems that can be found around the city. Perhaps the scale is slightly smaller, but the buildings are no less important for the city and its people.

Aside from written records, buildings serve as primary sources that can teach future generations. The relationship between people, their values, and the structures they build helps us identify with Quincy's past.

Bridget Quinlivan graduated from Quincy University and Western Illinois University. She is a member and volunteer at the Historical Society and an English/writing specialist for the TRiO program at John Wood Community College.

Sources

Curtis, Grant M. Quincy Illustrated: A Sketch of Early Quincy and a Description of the Quincy of To-Day Containing Over Two Hundred Illustrations, and a Careful Review of Quincy's Advantages as a Commercial and Manufacturing Center. Quincy, Illinois: Quincy Daily Journal, 1889.

Francine Haber, Kenneth R. Fuller, and David N. Wetzel. Robert S. Roeschlaub: Architect of the Emerging West, 1843-1923. Denver: Colorado Historical Society, 1988.

Krautheimer,Richard. Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984.

Quinlivan, Bridget. "Quincy, Illinois: The Value of the Past in the Present." Western Illinois Historical Review. Vol. II, Spring 2010: 64-87.

Watkin, David. A History of Western Architecture. London: Hali Publications, 2005.