Quincy anti-slavery voices, 1839: 'American Slavery As It Is'

The emancipation movement in Illinois took root in Quincy and Adams County, where the state's first anti-slavery society was formed in 1835. Slavery's enemies were organizing more fervently by the 1830s, and as the nation expanded American abolitionists followed. From New England to southern states and even to the new slave state of Missouri, citizens were uniting to fight its extension; including early Quincy residents who contributed to an antebellum brand of citizen journalism.

In 1839 the American Anti-Slavery Society published "American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses." Theodore Dwight Weld organized this anti-slavery propaganda along with his wife, Angelina, and her sister, Sarah Grimke. They scoured thousands of southern newspapers to gather evidence to combat pro-slavery arguments, in many instances with slaveholders' own words. Runaway slave bulletins and personal narratives from southerners and visitors to slave states were included in the investigation.

Several Quincyans made declarations in this abolition bulletin. The young town attracted some Americans who denounced slavery, and their association with Weld connected them to the most ardent advocates of freedom in the U.S.

Charles Renshaw preached for Quincy's Congregational Church from July 1838 to Feb. 1839. He knew Weld personally, and they both were members of the "Lane Rebels," a group of students expelled from Lane Seminary in Cincinnati, Ohio, for organizing an anti-slavery debate. Renshaw wrote Weld personal letters to his New York City headquarters after they parted. He was a county anti-slavery agent for several years, and then moved to Jamaica with his wife for missionary work.

A southern native, Renshaw relayed an experience he had while living in Kentucky: "In a conversation with Mr. Robert Willis, he told me his negro girl had run away from him sometime previous. He was convinced she was lurking around, and he watched for her. He soon found her ... got a rope, and tied her hands across each other, then threw the rope over a beam in the kitchen, and hoisted her up by the wrists, ‘and', said he, ‘I whipped her there til the lint flew I tell you'. I asked him the meaning of making the lint fly, and he replied ‘til the blood flew.'"

Tobacco planters sometimes forced their slaves to eat the loathsome tobacco worms they missed in picking the crop. Judge Menzies, a Kentucky slaveholder and elder in the Presbyterian Church, told Renshaw about this practice. He also spoke of the Presbyterian minister and church where he lived: "The minister and all the church members held slaves. Some were treated kindly, others harshly. There was not a shade of difference between their slaves and those of their infidel neighbors, either in their physical, intellectual, or moral state; in some cases they would suffer in comparison."

Renshaw sent Weld a letter he received in Quincy dated Jan. 1, 1839, in which the author accused neighboring Missouri slave owners of brutality. Fearing retribution, Renshaw did not reveal the author's name but added a note from Henry H. Snow, a Quincy judge, and Willard Keyes, a founder of Quincy, who testified to the author's character.

The informant had lived in Missouri for many years, and he shared several anecdotes. He accused John Mackey, a rich slaveholder living in Pike County, Mo., of murdering his 14 year-old slave Billy. "He buried him away in the woods; dark words were whispered, and the body was disinterred." The coroner concluded that the boy had died of a fractured skull. "The case was brought into court, but Mackey was rich; and his murdered victim was his slave; and after expending about $500 he walked free."

This nameless friend of Renshaw also charged a Mrs. Mann of murdering Fanny, a slave woman Mann had hired out from Charles Trabue, who lived near Palmyra, Mo. The mistress was known to use her "six pound paddle" to torture slaves, and when Trabue heard of Fanny's death he commenced suit for his property. The coroner brought in a verdict of death by the six pound paddle, and Mrs. Mann briefly left the area. When she returned, her friends "found means to protract the suit." Renshaw made lasting impacts on the anti-slavery cause during his brief stay in Quincy.

Ezra Fisher was a Baptist minister who was stationed in Quincy from 1836-1841, and Dr. Richard Eells was a deacon in the Congregational Church. They both attested for the honesty of another man who wanted to remain anonymous. Their names appear in the section "Testimony Of A Virginian."Eells and Fisher said of the man: "We have great confidence in his integrity, discretion, and strict Christian principle." The Virginian then described seeing droves of hundreds of slaves, all chained and fastened together in long lines. He had seen hundreds of droves and chain-coffles, and said, "every coffle was a scene of misery and woe, of tears and brokenness of heart."

Dr. Eells was a well-known abolitionist from Quincy who lost a court case for aiding a fugitive slave escaping through town. The Eells case was the only Underground Railroad case appealed all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld the conviction.

Dr. David Nelson, one of Quincy's most outspoken abolitionists until his death in 1844, wrote of an incident he witnessed "that came under my observation as a family physician." He described the moment he saw the mistress of the house thrust her servant girl's hand into scalding water as punishment for a trifling offense.

George Westgate, a member of the Congregational church along with Eells, gave the most narratives of anyone in town. He navigated the old southwestern slave states as a keel boat trader for 12 years, and he returned with startling impressions of slave culture. He described the crude lodging and clothing he witnessed in lower Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana, the long workdays that began at 4 a.m., and scant diets that slaves survived on. He wrote about agonizing whippings on Widow Calvert's plantation near Rodney, Miss. "The expression ‘whipped to death' as applied to slaves, is common at the south."

Westgate also said that a planter from Orange Five Points plantation near New Orleans had placed a runaway slave on his keelboat to be sent back home. The young slave told him he expected to be whipped almost to death. "Pointing to a graveyard, he said: ‘There lie five who were whipped to death.'" He added: "Overseers generally keep some of the women on the plantation; I scarce know an exception to this. Indeed, their intercourse with them is very much promiscuous â€" they show them not much, if any favor. Masters frequently follow the example of their overseers in this thing."

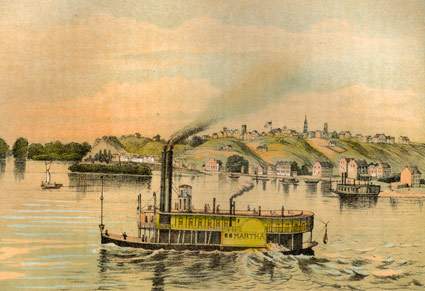

According to Quincy's earliest city directory of 1848 and others, Westgate lived on the same block as several other abolitionists near Fourth and York, with Missouri slavery in full view across the river.

"American Slavery As It Is" sold 100,000 copies in its first year of publication. Weld relied on the horrifying aspects of slavery to emphasize its need for destruction. Most of the reports are graphic but accurately portray how absolute power can corrupt people. Harriet Beecher Stowe was heavily influenced by its stories for her book, Uncle Tom's Cabin. American citizens who contributed knew that it would be controversial, but they were willing to help inform the public of slavery's evils.

Heather Bangert is a field/lab technician for Illinois State Archeological Survey. She is a member of Friends of the Log Cabins, has given tours at Woodland Cemetery, and is involved with several other local history projects.

Sources

Barnes, Gilbert, and Dwight L. Dumond, ed. Letters of Theodore Dwight Weld, Angelina Grimke Weld, and Sarah Grimke, 1822-1844. 2 vols. Gloucester, Mass.: Peter Smith, 1965.

Carter, William, and S. Hopkins Emery. A Memorial of the Congregational Ministers and Churches of the Illinois Association. Quincy, Ill.: Whig and Republican Steam Power Press, 1863.

Quincy City Directory. Quincy, Ill.: Dr. J. S. Ware, 1848.

Weld, Theodore Dwight. American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses. New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1839.