Come to Freedom, The Disastrous Mission to Free Slaves in Missouri

Part 2: Come to Freedom

There was a constant flow of slaves through Illinois and Quincy in 1841. Many of the workmen on steamboats plying the river were enslaved. Immigrants from the old slave states in the East, traveled to Missouri, by virtue of the Missouri Compromise of 1820 the only slave state north of the latitude line 36 degrees, 30 minutes. Thousands of migrants, many with slaves in tow, traveled the National Road from Washington, D.C. to Illinois then up to Quincy. No one ever tallied what percentage brought slaves with them. It was illegal to reside in Illinois or the other states carved from the Northwest Territory and own slaves, but you could travel with your slaves unmolested. You could even pay innkeepers to lock your slaves up for the night. You could pay the sheriff to discipline your slave for you. This was true throughout the United States. The fancy resorts of Saratoga, New York bustled with southern families and their slaves as plantation owners’ families sought to escape the oppressive heat of the south. In 1841, there was little fear of having ones’ slaves molested by abolitionists and enticed to run off in “free” states.

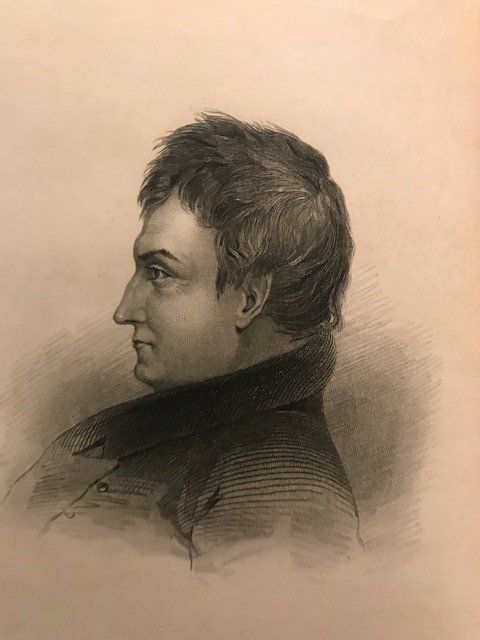

Among the small cadre of abolitionists in Quincy, George Thompson, Alanson Work, and James Burr had determined to put their anti-slavery beliefs into effect and actually go into Missouri to try to liberate slaves. Burr and one of the other two – they never confessed who it was – had already made one foray into the state which had been a failure. On July 11, 1841, the three men rowed across the river again. They banked the boat near the Fabius River. Thompson stayed with the craft while Burr and Work went inland. Burr went back to the Woolfolk farm. Mr. Woolfolk was not at home, so the men took the opportunity to speak with the slave woman who kept the house. They told her they were there to take her to freedom the next day if she wanted to go. They told her to be at a willow thicket near the river the next night to begin her trip to Canada.

The two abolitionists then went into the fields and spoke with a group of slaves hauling lumber without supervision. The slaves were named Paris, Allen, Prince, John, and the same Anthony with whom Burr had spoken to on his earlier trip. The slaves were puzzled when the white men approached and spoke to them. Slaves were not used to being addressed as equals. There were very strong cultural conventions that people followed. Slaves did not look white people in the eye when speaking with them. Slaves had to be deferential to white people. These Illinois men did not follow the unwritten rules. Work and Burr made the same pitch they had made to the woman at the house: if you want to be free, we will get you on the road to Canada. No doubt, the three naïve abolitionists were surprised the slaves did not seem to jump at the chance.

The problem was simple. The slaves had never heard of Canada and had no idea slavery did not exist there. They were confused by the three abolitionists. Burr and Work talked to the slaves and quoted the Bible to them as no white people had ever done before. This only confused the group more. Slaves were accustomed to hearing only those Bible verses that supported slavery. How many sermons had they heard from white preachers on Paul’s admonishment in Philemon that slaves should obey their masters?

Unable to convince the slaves on the spot to run away, Work and Burr told them they would meet them the next night at a nearby willow thicket and would talk to them more. They agreed to explain to the slaves the details of the trek to Canada and their chance for freedom. If the slaves wanted to go the next night, they would row them across the Mississippi and start them on their way. Then Work and Burr went back to the river and Thompson rowed them back to Quincy. They were buoyed, no doubt by the thought that the next night with a little more explanation, they could bring a batch of slaves to the Mission Institute. It was not to be.

After the abolitionists left, the slaves talked among themselves. No white man had ever shown an interest in their well-being. This talk of freedom seemed fantastic. They were unable to take Work and Burr at face value. Instead they arrived at the only conclusion that made sense to them. They knew that they had value. A frequent threat to keep slaves in line was to threaten to sell them downriver. Slave owners told exaggerated stories of conditions on plantations in Louisiana to coerce them into obedience.

The slaves decided that the abolitionists were slave thieves who would sell them to a place worse than their lot in Missouri. They selected Anthony as their leader and approached the white man for whom they had been felling and hauling logs. No doubt, William P. Brown was surprised that Anthony would approach him. It took a lot of courage on Anthony’s behalf. He didn’t belong to Brown. His owner was Richard Woolfolk. Brown had simply hired him from Woolfolk to work on cutting trees. Of course, Woolfolk got all the money for Anthony’s labor.

Brown knew exactly what to do when Anthony explained to him how Work and Burr had approached the slaves. Brown knew what an abolitionist was, and that slavery had been outlawed in Canada. He knew that the abolitionists had to be caught. However, he immediately realized he had a problem. No white person had heard Work and Burr speak. Under Missouri law, no slave could testify in court – not even against an abolitionist. Brown sounded the alarm and a posse was raised. The slaves were promised a reward for cooperating with the slaveholders. The trap was set.

Continues with Part 3: Capture, Trial, and Prison

Sources

Dempsey, Terrell. Searching for Jim, Slavery in Sam Clemens’s World. Columbia, MO:

University of Missouri Press, 2003.

Palmyra Missouri Whig , July 17, 1841.

Palmyra Missouri Whig , September 25, 1841.

Circuit Court records of Marion County, Missouri.

Liberator , August 27, 1841.

Liberator , October 8, 1841.

Liberator , November 5, 1841.

Liberator , December 10, 1841.

Thompson, George. Prison Life and Reflections . Hartford, Conn.: A. Work, 1853.

https://www.weather.gov/timeline