Communicable diseases were scourge in 19th century

Today when we talk about health, we frequently refer to exercise, eating right and other lifestyle concerns.

When Illinois was the frontier, health meant not dying from communicable diseases. Those diseases were mostly eradicated by the 21st century but were a scourge throughout the 19th and earlier half of the 20th centuries.

Documented health in Illinois began in 1674 when Father Jacques Marquette and his party recorded diarrhea as the cause of their extended camp on the Chicago River in 1674.

With river travel as the dominant form of transportation, the journals of the earliest explorers in the territory that became Illinois recorded tertian fever, intermittent fever, ague and yellow fever in the Mississippi River Valley.

These malarial-type diseases were caused by insects that thrived in the swampy areas along the rivers.

The first documented quarantine was in 1799, when Illinois residents were prohibited from crossing the Mississippi River to St. Louis due to a smallpox outbreak.

In 1927, the Illinois State Department of Public Health published a book to commemorate its 50th anniversary, with 15 pages devoted to Quincy.

The section begins with descriptions of the city: “It was once ‘The Crossing’ and ‘The Track’s End.’ Here in the early days of the settlement of the Great West, the flood tide of immigration stopped for

a time before it crossed the Mississippi by ferry. … Quincy was then a stormy, seething mob. It was the frontier, the jumping off place. Finally came the railroad bridge… streams of men who came after flowed through without stopping.”

With the “streams of men” came cholera. It first appeared after the Black Hawk War in 1832 with troops spreading it throughout the state.

The cholera bacterium is found in food or water contaminated by someone who has the disease.

It spreads rapidly and was the first epidemic in Quincy in 1833-34 when 6 percent of the population died.

The “sulphur remedy” was used by local doctors.

Another remedy reads: “The process consisted of anointing with oil, prayer, brandy, psalm singing, flannels, exhortations

and hot water. The prescription was carried into effect with great vigor and perseverance throughout the entire night and in the morning the patients were quiet and without pain, — both being dead.”

As more people settled the state, typhoid appeared (1845) as well as meningitis, scarlet fever, diphtheria, erysipelas (a rash usually caused by streptococcal bacteria), and tuberculosis. Few had any idea how to help the sufferer or cure these diseases.

Doctors were scarce on the frontier when the first doctor arrived in Quincy in 1824.

These early doctors would see their patients by horseback and then later by buggy. They did have offices but mostly saw patients in the home. The doctor would carry what was necessary to treat his patients in his saddlebag.

His equipment would include a lancet, stethoscope, syringes, bandages prepared from strips of muslin and obstetrical instruments. He would prepare his own medicines but relied heavily on quinine and calomel (a purgative).

Many early Quincy doctors included a drugstore in their practice.

In 1850, Quincy physicians organized the Adams County Medical Society. They organized to help each other during epidemics and to promote the profession through standards and membership criteria. “The society gave much attention to sanitary matters and by its persistent efforts secured the creation of a board of health by the city and the adoption of a system of mortuary registrations, several years previous to the passage of the present State laws relating to

these matters.” The board had five members, three of whom were physicians.

This board hired a city physician to look after the indigent sick and began a vaccination program in 1871. This was not always a happy position as one report from the city physician in 1873 states: “I congratulate myself upon my release from such a public burden at such an insignificant salary, … and I thank the Honorable Council for their practical appreciation of my services by refusing me additional pay for services made additional by the severest and most protracted winter we have ever seen.…” Published mortality tables from 1875 show the leading causes of death to be typhoid (caused by food or water contaminated with the bacteria Salmonella Typhi), tuberculosis, pneumonia and diphtheria. Deaths in Quincy from all communicable diseases continued to drop except from influenza, which rose in 1918 during a worldwide epidemic.

Finally with a clean water supply, ample sewers and vaccinations, typhoid was practically eliminated by 1917.

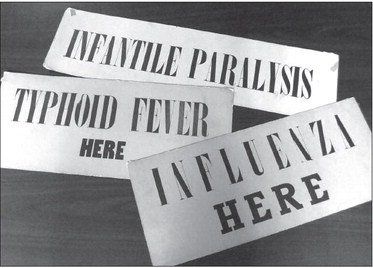

In the early part of the 20th century childhood diseases were a considerable cause for concern in Quincy, and the city would quarantine the family for the safety of the community. Large orange signs were placed on the house.

The Public Health Department kept track of these diseases and reported them, with measles being the most reported communicable disease between 1916 and 1927. Whooping cough was a distant second. Among adults, influenza would spike during certain years with pneumonia and tuberculosis having consistently high numbers reported.

Vaccines soon became more prevalent and antibiotics were discovered.

They made a huge difference in both childhood and adult diseases. But it wasn’t until 1943 that the first dose of penicillin arrived in Quincy and saved the life of a 9-year-old girl who had been in Blessing Hospital for six weeks suffering from staphylococcus aureus septicemia and osteomyelitis.

Her physician had to request release of the drug for civilians from a Boston hospital, with the drug arriving within 24 hours. The newspaper stated: The patient “appreciates the help that has been given her by this new development of science and is looking forward to complete recovery from illness.”

Arlis Dittmer is a retired medical librarian. During her 26 years with Blessing Health System, she became interested in medical and nursing history — both topics frequently overlooked in history.