Quincy missionaries helped slaves escape to Canada

Elias E. Kirkland and Elizabeth “Fanny” Clary met at Quincy’s Mission Institute in its fledgling years, arriving in the late 1830s.

A courtship developed between these New England students and they wed after graduation.

The Rev. David Nelson’s missionary training school is legendary for its antislavery stance and Underground Railroad work.

The Kirklands would combine their humanitarian efforts when they settled in Ontario to assist fugitive slaves who fled there.

Elias Kirkland knew the radically antislavery students of the institute before his Canada mission began. He traveled to Hancock County with classmate George Thompson, and in 1841 they founded the first Congregational Church in Plymouth (Round Prairie), Ill.

That same year Thompson was imprisoned in Palmyra, Mo., for trying to entice slaves away from their masters. The Work, Burr, Thompson Trials brought more notoriety to the abolition movement.

Kirkland and Clary were married at the Mission Institute Chapel in 1842, and that same year the couple began their missionary duties at the Dawn Settlement in Canada West.

Kirkland had been ordained as a Wesleyan

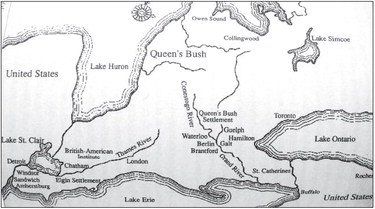

Methodist minister and the pair became teachers at the British American Institute near Chatham. They lived in a cabin with other missionaries and school founder Hiram Wilson.

Wilson was a steadfast abolitionist who founded the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society and created the school with fugitive slave Josiah Henson. Wilson had been one of the “Lane Rebels,” a group of students expelled from Lane Seminary in Cincinnati, Ohio, for organizing an antislavery debate.

Another “Rebel” was Charles S. Renshaw, who preached for Quincy’s Congregational Church in 1838-39 when the Kirklands were students at Mission Institute.

The Kirklands lived Mission Institute’s objectives when they helped fugitive

slave families at the British American Institute, which opened with nine young men as the first students.

More pupils arrived and Fanny Kirkland helped found the Committee of Education in Canada West to address the needs of female students.

In 1845 the Kirklands moved farther inland to an area of Canada known as the “Queen’s Bush Settlement.” Missionaries and an increasing numbers of fugitive slaves essentially squatted on the many acres of unsurveyed land.

The Kirklands joined their old friend Fidelia Coburn from the British American Institute to open a school. Donations and from the American Missionary Association were scarce, so Elias Kirkland cultivated crops to supplement their needs.

Free Frank McWorter’s

first free-born child Squire McWorter and his wife, Louisa, were in Canada West when the Kirklands were stationed in the region.

Their son Squire Jr. was born in Chatham, Ontario, in 1846. The elder Squire may have been assisting fugitive slaves to Canada on this journey, as he learned from his older experienced brothers. The McWorter family had known the route to Canada from Kentucky since the 1820s, and family oral history claims that Free Frank’s sons made frequent trips to Canada while living in Kentucky, and helped slaves while living in New Philadelphia, Ill.

Louisa Clark McWorter and her brothers Simeon, Monroe and William Clark moved to Quincy from New Philadelphia a few

years later, working with other free black Quincyans for John Van Doorn’s sawmill.

In 1849 the Kirklands moved to the fugitive slave community of New Canaan, near Amherst-burg. They opened a school for black students, and it became integrated as more white settlers arrived.

Kirkland reported that his townships had “between 3,000 and 4,000 fugitives.” He also addressed interracial audiences during Wesleyan Methodist camp meetings in the 1840s.

After passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, more refugees flocked to Canada. Kirkland reported: “Our settlement is rapidly enlarging. The Fugitive Slave Law appears to be a dead letter in its operation, judging from the number who get safely to Canada.”

Kirkland met former slave and abolitionist Henry Bibb, a fugitive who escaped in 1841 from his Cherokee owner, caught a steamboat from St. Louis to Cincinnati, and settled in Michigan until the new law prompted him and his wife to cross the Detroit River to Canada.

He started the newspaper Voice of the Fugitive in 1851, an antislavery weekly.

Bibb was the founder and president of the Refugee Home Society, with its first meeting in Detroit in 1851. Kirkland was secretary. The Society sought to purchase land in Canada for new refugees.

In 1854 the Kirklands left Canada and moved to Michigan.

Bibb’s death that same year, along with increasing tensions among abolitionists in Canada West, made the Kirklands disillusioned with missionary work.

After 20 years laboring in fugitive slave settlements, the family took up farming. In 1875 Kirkland returned as an agent for the Home Missionary. In 1876, Fanny Kirkland wrote the family’s last known letter to the American Missionary Association, and she enclosed a $5 donation for missionary work.

Heather Bangert is a member of Friends of the Log Cabins, has given tours of Woodland Cemetery and the John Wood Mansion, and is an archaeological field/lab technician.