Cures for drunkeness flourished in late 19th century

President George Washington, a whiskey distiller himself, thought that distilled spirits were "the ruin of half the workmen in this Country."

His successor, John Adams, whose second son, Charles, was a drunkard, asked, "is it not mortifying ... that we, Americans, should exceed all other people in the world in this disgusting, beastly vice of intemperance?"

Between 1790 and 1840, Americans drank nearly a half pint of hard liquor per man per day, and by the late 19th century with social problems related to alcohol escalating, efforts began to curb excessive imbibing.

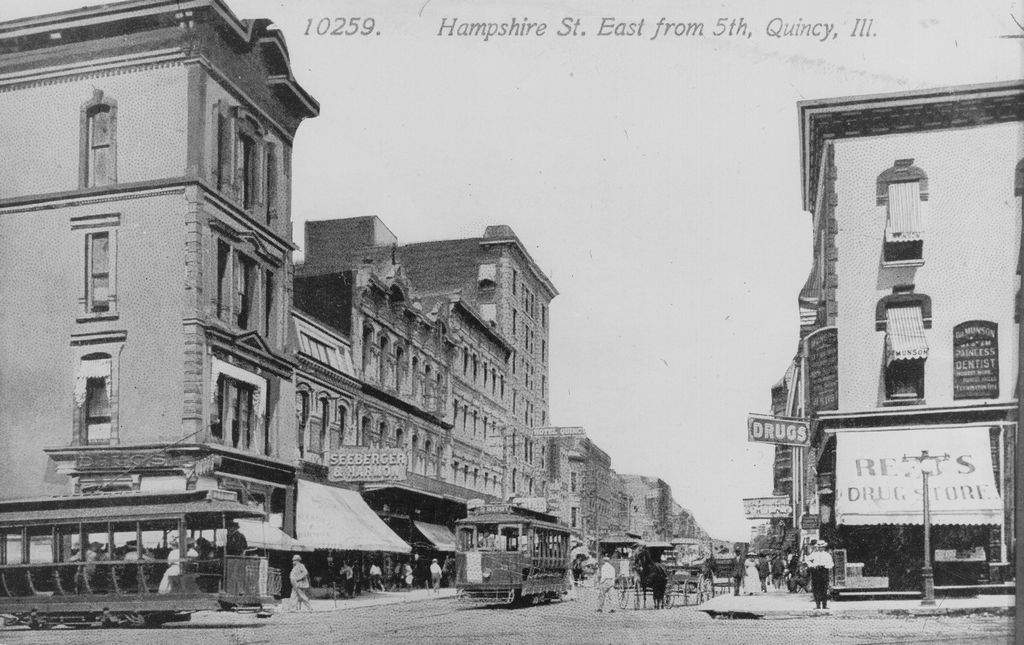

Like much of the country, Quincy had made public intoxication illegal by the 1880s, but without a way to measure inebriation, arresting officers decided who was drunk. During testimony at a local trial, a policeman said, "the subject was sitting on a curb mumbling to himself and not sure of who he was, his wife's name, or how to get home."

Papers published offenders' names and often gave detailed accounts of their intoxication and arrest; judges handed down hefty fines and, sometimes, jail sentences. Authorities viewed punishment and incarceration's forced abstinence as the most effective antidotes.

Shocking cases sometimes made Quincy headlines: a man found drunk in church, intoxicated children sent home from school, a drunken officer asked to resign. Drunkenness could also be grounds for divorce--a scandal and social stigma granted only in extreme cases.

Since coming to town in 1892, Quincy's Salvation Army held regular "Save the Drunkards Meetings" and marched through downtown streets pleading with sinners to repent; more established churches, such as Vermont Street Methodist Church, made the "devil's drink" the theme of many sermons. Ecclesiastical views, like those of the larger society, saw drunkenness as a sin needing repentance.

Illinois law considered drunkards insane and subject to incarceration without any rights, as seen in October 1900 when Quincy Judge Carl E. Epler sentenced Perry M. Weiss to Jacksonville's Insane Asylum after a witness testified, Weiss "could take a larger drink of booze-water than any man I had known." Attitudes toward drunkenness, though, were changing.

Because many Civil War veterans had serious problems with alcohol, Quincy's Illinois Soldiers and Sailors Home founded a Soldiers' Christian Temperance Union in 1897 modeled on the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), which had been established in Hillsboro, Ohio, by Annie Wittenmyer and Francis Willard two decades before. When Quincy formed its branch of the WCTU in 1910, female drinking and alcohol's effect on families gained more attention. Among its many activities, this local chapter held an annual essay contest for students on the theme, "What is the Harm in a Glass of Beer?" and at its peak had over 400 paid members. As with churches, the WCTU emphasized willpower and moral choice.

Illinois Rep. Ross Graham of Vandalia introduced a bill in the state Legislature in January 1899 to fund two inebriate asylums, one in Dwight and another in his hometown, and one year later lawmakers passed it. Taxes on saloon keepers and stiff fines on taverns serving people who had been in these asylums maintained these facilities. Quincy's St. Mary and Blessing hospitals did not admit inebriates (although Swedish physician Dr. Magnus Hass had coined the term "alcoholic" in 1849, widespread use did not begin until the 1930s) and sent chronic cases to the Dwight asylum. Other serious offenders usually ended up in the Adams County Workhouse or--if they could afford it--in the back wards of local sanitariums or old folks homes.

During the late 19th century, some doctors began treating inebriation as a disease, and the search for a cure began. Medical thinking did not widely recognize "chronic diseases" requiring continual treatment, so researchers sought cures. These ranged from apple pie to goat's milk, horse blood, corrective eyeglasses, vegetarianism, acid phosphate and hypnotism. Many physicians themselves contributed to the problem by prescribing tonics and patent medicines that often contained alcohol, as well as cocaine, marijuana and wormwood. A local newspaper report told of a breakthrough discovery that "inebriate mother's milk contained alcohol" and soon sterilization to prevent drunkards from breeding became the most radical cure. University of Chicago professor Albert P. Matthews even announced that "alcohol is a food and every man is a human distillery."

Dr. Leslie E. Keeley, who stated, "drunkenness is a disease and I can cure it," introduced the "Keeley Cure" in 1879, which for the next 50 years would be the most popular one. Sennewald Prescriptions distributed it nationwide, and most local drug stores sold it. An enthusiastic customer wrote, "Now that the Quincy Whig has discovered the merits of the Keeley Cure, wonder they don't take a round or two. It's good for cocaine, too." Ingredients in his "secret formula" reportedly contained morphine, willow bark, ammonia, atropine, as well as alcohol itself. Fervent use continued, though, and followers founded the Keeley League, a self-help group that became the prototype for Alcoholics Anonymous--a recovery method begun in the 1930s that went on to become the most successful program in history for maintaining long-term sobriety.

Still, many doctors refused to prescribe cures and believed only in the moral reform of drunkards.

Cures for the excessive use of alcohol waned with the passage of the Volstead Act (hailed by proponents as the "ultimate cure") on Oct. 28, 1919, which carried out the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, prohibiting the production, sale and transport of intoxicating liquors. During the 13 years of Prohibition, Illinois' inebriate asylums folded and jurisprudence again usually usurped remedies. On Oct. 24, 1923, Quincy Judge Charles G. Nauert sentenced Henry Maas, the "confessed inebriate of Melrose neighborhood," to 60 days on the rock pile at the Adams County Workhouse as the proper way to purge him and others of the demons driving them to drink.

Joseph Newkirk is a local writer and photographer whose work has been widely published as a contributor to literary magazines, as a correspondent for Catholic Times, and for the past 23 years as a writer for the Library of Congress' Veterans History Project. He is a member of the reorganized Quincy Bicycle Club and has logged more than 10,000 miles on bicycles in his life.

Sources:

"Digestion of Alcohol," Quincy Daily Herald, Feb. 2, 1903, P. 6.

"Judge Nauert Sentences Two to Workhouse," Quincy Daily Herald, Oct. 24, 1923, P. 12.

Pittman, Bill, The Roots of Alcoholics Anonymous. Center City, Minn.: Hazelden, 1988, P. 31-32.

"Policeman Drunk; Asked to Resign," Quincy Daily Whig, Sept. 5, 1917, P. 3.

"Prizes for the Pupils," Quincy Daily Herald, April 18, 1910, P. 3.

Rorabaugh, W.J. The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979, P. 5 and 6.

"The Scientist," Quincy Daily Herald, July 13, 1894, P. 4.

"Three Insane Cases Heard," Quincy Daily Whig, Oct. 3, 1900, P. 8.

Wilcox, David F. Quincy and Adams County: History and Representative Men: Chicago: Lewis Pub. Co., 1919, Vol. 1, P. 524 and 25.