Statue brought honor to 'unnoticed' military leader

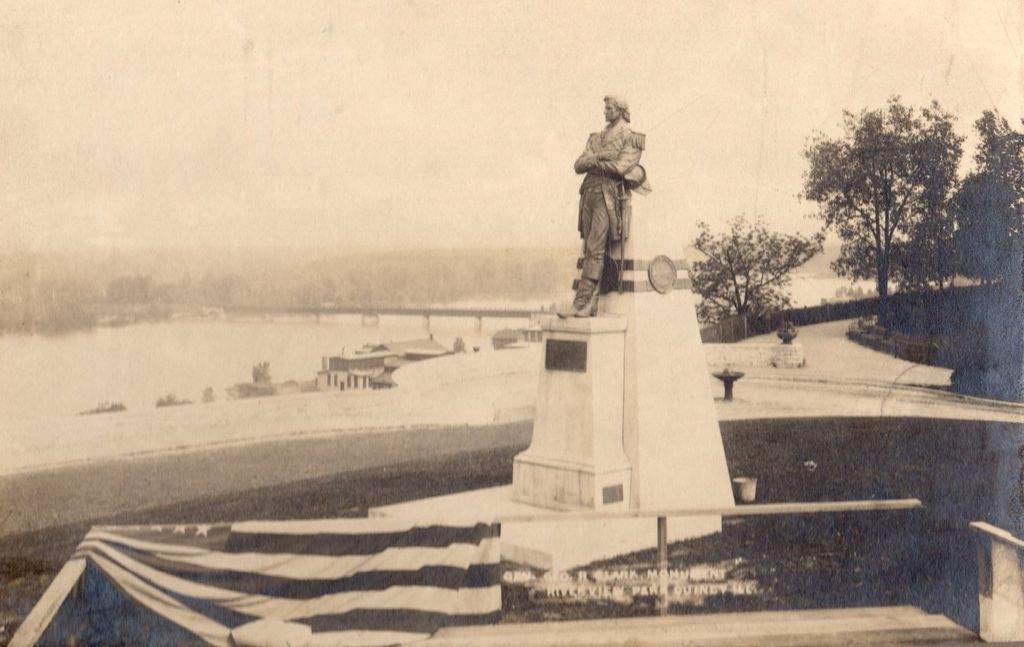

George Rogers Clark was an important military leader in the Revolutionary War and is commemorated with an impressive statue in Quincy's Riverview Park. The statue portrays a heroic figure confidently gazing across the Mississippi River toward land once the home of Native Americans, a vast territory tossed back and forth between France and Spain and then ceded to the United States by the terms of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

"It is said that the idea of the monument came to him (state Rep. Campbell Hearn) from a chance remark dropped by Henry Watterson, the famous Kentucky newspaper editor," as quoted in Elizabeth Parker's "History of the Park System of Quincy, Illinois." Watterson mentioned to Hearn that "Clark had, as yet, been left unnoticed by the states which he had saved to the country… and resolved to work for … a suitable statue in his honor."

Responding, Hearn introduced House Bill 10 in early January 1907. The bill originally appropriated $20,000 for the "construction and erection of a suitable monument" but was eventually reduced to $6,000. The legislation was enacted May 23, 1907. A commission, authorized by the law, incurred $5,826.56 in expenses with $3,750 paid to sculptor Charles J. Mulligan, a graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago and a student of Lorenzo Taft, for his "bronze work for monument." The balance went to local businesses.

In May 1908, Mulligan presented six models to the commission. "The one chosen represents the hero (Clark) in youthful but mature manhood. Clad in the uniform of a Continental soldier with his arms folded across his breast, leaning back slightly against a stone, he seems to view in retrospect the achievements of his career."

Original plans called for erecting the statue "in the north end of Riverview Park." However, E. J. Parker, president of the Quincy Boulevard and Park Association, called for a more prominent location, "where it would be seen distinctly from the river and the bridge." Parker's preferred site, however, was not in the park, so about $9,000 was spent to acquire additional land that became known as George Rogers Clark Terrace.

The statue and its granite base arrived in December, and the statue "was swathed in cloths soaked in vinegar to bring out the peculiar luster of the bronze and was boarded in for the winter, thus to remain until spring when the unveiling exercises were to be held," according to Elizabeth Parker.

The Quincy Herald reported that the May 22, 1909, dedication ceremony would feature Illinois Gov. Charles S. Deneen, Sen. Hearn, Quincy Mayor John A. Steinbach and "Master Rogers Clark Ballard, of Louisville, Ky., aged eleven years, and a great-great-grandson of General Clark's sister," who would unveil the statue.

Unfortunately, news arrived from R.C. Ballard Thruston, the lad's uncle, that the boy was seriously ill and unable to attend. Sadly, a telegram brought the news: "Little Rogers Clark Ballard died at two o'clock" on May 15, 1909.

Subsequently, Temple Bodley, another Clark descendant, was invited and declined, but he did commit his 12-year-old daughter, Ellen Pearce Bodley, to attend. Ellen, a great-great-great niece of George Rogers Clark, was accompanied by her mother to Quincy.

"The day opened a little threatening (but) the sun came out bright later," and soon "the weather was all that one could wish." A crowd of about 9,000 people gathered for what the Quincy Daily Whig called, "the most auspicious general public celebration held in this city since the memorable dedication of the Illinois Soldiers' and Sailors' Home … in 1886."

The festivities featured a parade, songs, an invocation and many speeches. Then Ellen stood on a table and pulled the cord releasing the draperies covering the statue. "There was a spontaneous outburst from the multitude that continued for some moments."

After the unveiling, E.J. Parker acknowledged the "artistic genius of the sculptor," and Sen. Hearn praised Clark's "remarkable campaign that destroyed British authority over the northwest territory." Finally, the monument was presented to Gov. Deneen who spoke glowingly of Clark's exploits.

A borrowed pitcher and tumbler on the speaker's table caught the eye of Mrs. Bodley, who asked if she might keep them. The hosts agreed and dispatched an emissary to their owner, whose pitcher and tumbler were on their way to Kentucky without her consent, to "negotiate … a settlement … in a manner mutually satisfactory." Ellen also received a "little spoon" as a symbol of thanks for her participation in the ceremony. Ellen eventually married and had a son, George Rogers Clark Stuart, who noted in my interview with him that he knew about the Quincy statue although he had never seen it. Regrettably, he had no recollection of the pitcher, tumbler or spoon.

In 1991, vandals damaged several Quincy monuments, including Clark's, "leaving a trail of paint on the statue's stone base." The Clark statue was restored in 1993.

Several years later, Bill Hearne, Sen. Hearn's grandson, requested a rededication of the statue after discovering "memorabilia including the original handwritten manuscript of my grandfather's comments" for the original dedication.

The rededication occurred Aug. 3, 1996. Hearne recalled that there "was quite a crowd on hand." The program mirrored the 1909 event, featured the introduction of Sen. Hearn's descendants and remarks about Sen. Hearn by Phil Germann and about Clark by Judge Robert Hunter.

Clark's significance in history, specifically his 1770s conquest of the Illinois country, has been heralded by biographers for winning the land between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River in the Paris Peace Treaty of 1783. Other historians have more accurately judged Clark's contributions toward a Mississippi River border as supplemental to the diplomatic negotiations between Great Britain's Lord Shelburne and the United States' team of John Adams, Benjamin Franklin and John Jay, and to the directions provided by the Continental Congress, specifically James Madison.

Regardless of which analysis one accepts, Quincy's statue of George Rogers Clark serves as a beautiful symbol of his important service during the American Revolutionary War.

Steve Schneider and his wife, Julie, are both former Quincyans who now live in Deerfield, Ill. He is vice president of the Midwest region for the American Insurance Association and manages government relations and public affairs over 11 states.

To learn more

For a complete history of the statue's conception and dedication, see "The View From Here: The Story of the George Rogers Clark Statue in Quincy, IL" by Steve Schneider, Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Volume 100, No. 4, Winter 2007-08.

Sources:

"Demise of Bright Boy." Quincy Herald, May 6, 1909.

"General Clark Statue, Erected By The State, Unveiled Today." Quincy Daily Journal, May 22, 1909, p. 6.?

Husar, Edward, "Vandals mar Clark statue in Riverview Park." Quincy Herald Whig, July 1991.

"Monument Dedicated." Quincy Daily Whig. May 23, 1909, p. 1.

"Official Program." Quincy Herald, April 19, 1909.

Parker, Elizabeth G., "History of the Park System of Quincy, Illinois," 1888-1917 Quincy, Ill., Jost and Kiefer, ca. 1918, 67.

Quincy Daily Whig, May 22, 1909.

Remarks by Sen. Hearn, May 22, 1909, Clark file, HSQAC.

"She Coveted the Pitcher." Quincy Herald, May 24, 1909.