Dear Anna, dear Leo: WWI love letters

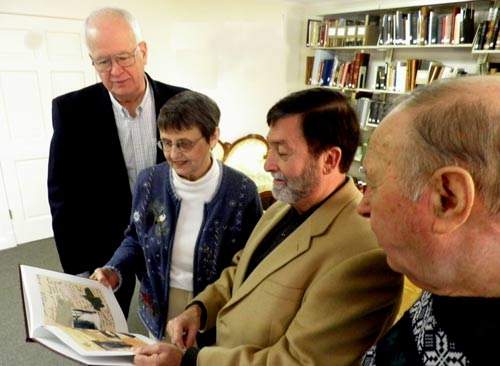

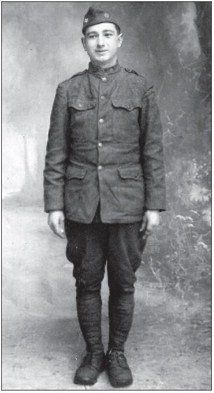

The old steamer trunk had been in the family for decades, ignored and taking up space. In 2012, descendants of World War I Army Pvt. Leo A. Veile of Quincy gathered around to see what secrets might be revealed within.

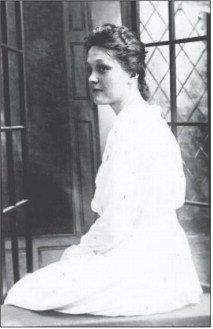

After the "war to end all wars," Leo had tucked away his uniform and mementos from his time in France. The woman who would become his wife added two boxes to the collection -- love letters containing more than 37,000 words that passed between them while he was "over there" and she was back home in Quincy awaiting his return.

The "soldier boy," as Anna Altgilbers sweetly called him, left Quincy to serve his country at the age of 21. Anna, then 23, was the object of his affection. Theirs became a long distance romance with no Twitter, cell phones, or Skype to keep them connected. Far from it. But they frequently took pencil and paper in hand to tell each other "the news" and to express their desire to be reunited at the earliest possible date.

"Be good and write as much as you can, as you know I like to hear from you," Leo wrote as he and his company sailed to France. "Don't forget that someday I'll be back in dear Old Quincy, Ill."

Luckily for them, he and the Company A, 128th Engineers arrived in France in October 1918, one month before the war ended. Even though the war was over before they had a chance to fire a shot, his company remained in France for almost a year, marching around the countryside, setting up and tearing down camps, and taking a little time to see the sights, including Paris.

The mail service was agonizingly slow for Leo. Although he had left the states in October, his first batch of letters from Anna did not catch up to him until January 1919. In a letter her wrote just a few days before Christmas, Leo expressed his frustration.

"The only Christmas present I want from Uncle Sam is all the mail he has for me that has been on the way to me for two months. It would sure do me more good than anything else. I know you are writing me as much as you can, and I will get it someday."

Back in Quincy, Anna worked as a domestic. She was kept quite busy by her employers and worked very hard.

"I just came back to get supper ... I had so much work that I never had time to write ... One of these days I will take a man's job," Anna wrote, "then I won't work on Sundays, either. I know I will."

Still, she was a young woman with as active a social life as possible, and Quincy seemed to offer quite an array of activities for her in early 1919.

"I went to the Orpheum a week ago Sunday to see ‘The Girl He Left Behind.' It sure was a grand play. Went to a dance a week ago Wednesday at the Arcade. The WCU had a party at school hall last Thursday and had a fine time. I think I will go to the dance Feb. 5 at KC Hall."

While Anna stayed busy in Quincy, life was not quite as exciting for lonely Leo, who had no fighting to do in France. But one day he happened to run into another soldier from Quincy. It was just what this homesick doughboy needed.

"I was sitting down eating a sandwich at the Red Cross Canteen," he said with an excitement Anna could sense from his letter. "A fellow came in and I thought I knew him. I said, ‘Buddy, where you from?' He said, ‘Quincy, Ill.' I said, ‘Put ‘er here ole boy, I'm from Quincy, too.'"

His new friend was named Charles Bennet. Turned out that Leo and Charles had worked together at the Electric Wheel Company in Quincy, although Charles had trouble placing Leo. Both had been in France in neighboring barracks but were unaware of each other until the chance encounter in the canteen.

"We sat down and talked for about an hour," Leo reported. "There are some more Quincy boys in this camp and there are some out in Fields 7-8-9. It is pretty hard to find them, unless you know what barracks they are in. But I sure am glad I met that fellow yesterday. Just as soon as he gets time we are going to round up the other Quincy boys. Bennet said there are a couple of Quincy flyers somewhere on this field and if I find them I am sure I will get a ride."

Airplanes were so new back then that they were not even referred to as such. Leo called them "machines," and he was eager to ride in one. One day, he got his chance. He went over to the airfields on a day when pilots were giving their mechanics rides in their biplanes. He was an interloper who had no business being at the airfield, but he tried to blend in. When one of the planes landed the pilot said, "Who's next?"

"I said ‘I am' and ran over and climbed in the machine, and my buddies came over and fastened the belt to hold me in the seat when the plane would be upside down," Leo explained in a letter to Anna. The other boys who went up for a ride had on leather coats, caps and goggles, but Leo only had a cap. It turned out to be a chilling experience.

"We ran over the ground for a little way and then I could feel myself going up in the air and I could feel my heart jumping up in my mouth," Leo related. "The wind was blowing something fierce and we got a lot of wind from the propeller and motor. My cap went off several times but I was afraid to let go with my hands to hold it, although there was no danger of me falling out."

But danger was in the air.

"When we made two loops, we were sailing around awhile and all at once the machine went straight down to the ground in a nose dive. We made a 300-foot dive and then straightened out again and went higher in the air. Gee, that made me think of you and home, and if I would ever see you again."

After a pass over the barracks "completely upside down," the pilot landed in the grassy runway and deposited his shaken cargo.

"I staggered like I was drunk. I was so dizzy and it seemed funny to step on the ground again. My ears were buzzing and I could hardly hear for a while ... I was trembling like a leaf. I sure was cold, too," Leo noted. "But, it was fine ride and I am going to take another if I ever get the chance!"

His letters described the many other experiences for Leo while in France, but the best experience was in June 1919, when he prepared to board the ship bound for home.

"Oo la la, when we get on the gang plank and pull out, in about 8 or 9 days we will see Miss Liberty. Oh boy, won't that be a grand and glorious feeling," he wrote. "Honey, your boy will be with you soon now, so cheer up for the war will soon be finished for me."

Steve Veile is the grandson of Leo A. Veile and Anna Altgilbers and grew up in Quincy. He is CEO of Communique Inc., a public relations firm in Jefferson City, Mo., a member of the HSQAC, president of Historic City of Jefferson, and an advertising professor at the University of Missouri School of Journalism.

Source

Altgilbers, Anna and Leo A. Veile, "Dear Anna, Dear Leo," compiled by Steve Veile. 2013. Research Library, Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.