Early Photography in Quincy Swiftly Evolved

The affixing of a visual image on material, a process that later became known as “photography,” dates from 1839 when French inventor Jacques Mande Daguerre created the first “daguerreotype.” By polishing a silver-plated copper sheet to a mirror finish and then treating it with mercury fumes, he produced light sensitivity.

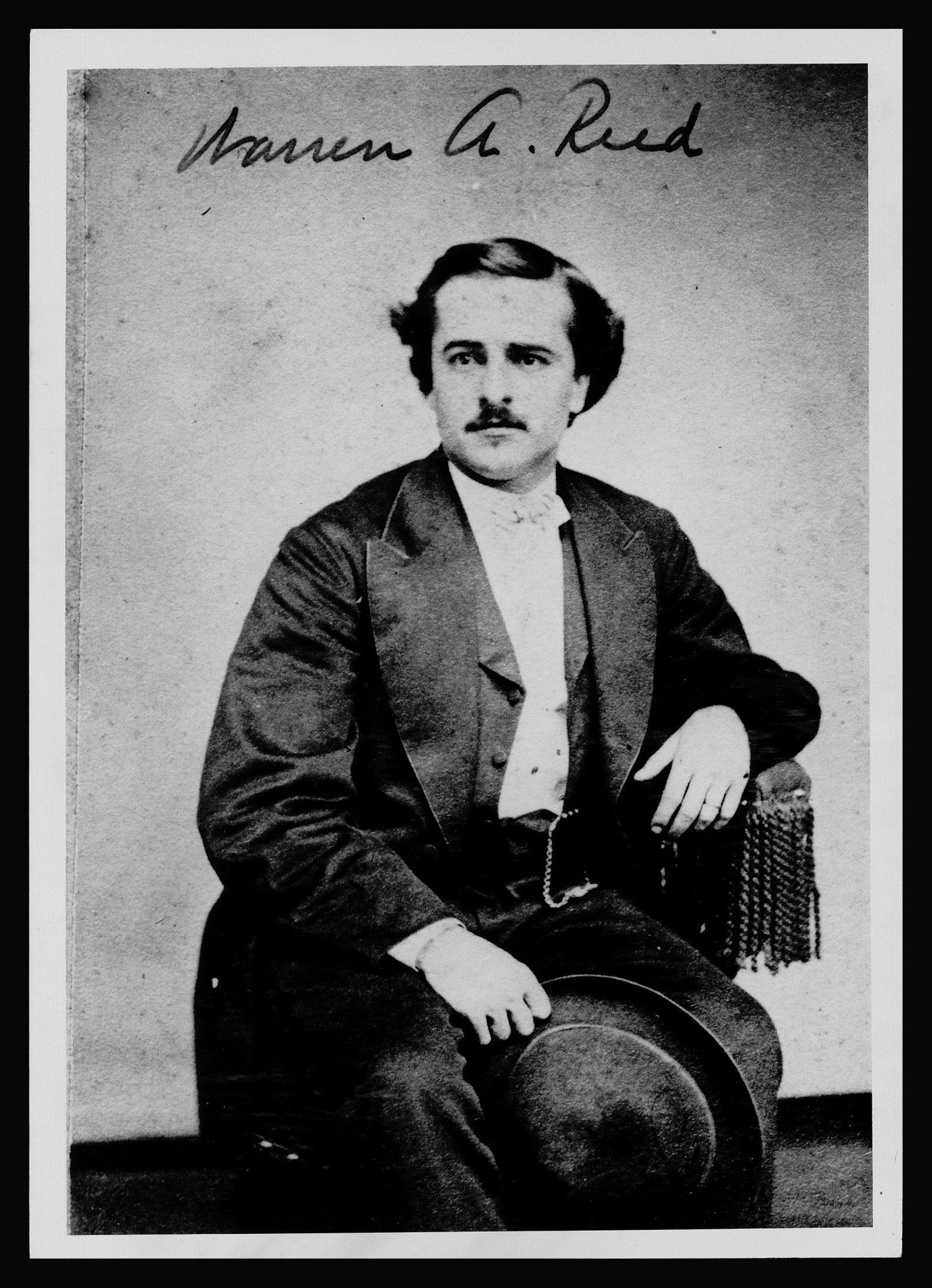

Nine years later, Warren A. Reed moved from his birthplace in Ohio and, along with his wife Candace, opened a studio named “Reed and Lady” on the west side of the public square in Quincy. This studio advertised to “take miniatures (portraits) of any size from a finger ring to a head nearly the size of life” and introduced “heliography,” as people called Daguerre’s technique, to local citizens. As with most proprietors across the country at this time, Reed did all of the processing and printing of images from negative to positive with darkroom chemicals himself.

During the early years of daguerreotypes, few folks in town could afford them. Those made overseas during the Crimean War, though, and displayed in Quincy allowed residents to see this new medium’s power to capture history unfolding. The Quincy Whig of December 3, 1854, said: “The historian may now break his tablet and throw away his pen—he is left out entirely in the background, eclipsed and buried by the daguerreotypist.”

Heliography burgeoned during the following decade, and by the mid-1850s Warren Reed had expanded his business to include “ambrotypes,” or images imprinted on glass. During his career, Reed opened a branch studio in La Grange, Missouri, and created a portfolio depicting stages in the construction of Governor John Wood’s octagonal mansion near 12th and State.

After Reed’s death in 1858, his wife sold his studio and opened her own pictorial salon named “Excelsia Gallery” at 103 Hampshire, with her sister and brother-in-law as assistants. Candace Reed supported herself, her two children and her mother-in-law with the business she owned in Quincy for over the next four decades. She also managed galleries in La Grange, Canton and Palmyra, Missouri. “Mrs. Reed” or “Mrs. W. A. Reed,” as she signed her works, adopted newer innovations and went from making daguerreotypes and ambrotypes to cartes de vistes and cabinet cards—images mounted on stiff paper or cardboard.

Critics across the country praised her many hundreds of excellent images—including renowned ones of Wyatt Earp and premier female self-portraits—and historians now recognize her as an important pioneering photographer.

Several Quincy studios opened after the Civil War, and most also sold “stereoscopes” capable of producing three-dimensional images when viewed through a left and right eye view of the same picture. Stereoscopes increased the popularity of “photography,” as people were now beginning to call heliography, enthralling children and adults alike. Soon the Miller and Arthur Photographic Supply Company started business at 502 Maine and sold cameras and equipment for individuals to personally take their own pictures. A hobby emerged from what had begun as a novelty.

Buffs established the Missouri and Illinois Photographic Association in Hannibal in 1884, and 11 years later Gem City enthusiasts formed the Quincy Camera Club. While art purists dismissed photography as a fad and a stunt, hobbyists began exploring the camera’s creative potential. During this era when club membership in the United States peaked, more organizations soon formed in Quincy: Amateur Photographic Association, YMCA Camera Club and the Fortnight Club. The Free Public Library began circulating books about photography to curious readers.

In the last decade of the 19th century, technology enabled newspapers to insert photographs onto its pages. In March 1892, the Quincy Daily Journal published an early “photo” of the new Gem City Business College at 7th and Hampshire. By the turn of the century, they would usurp illustrations and become an integral part of local newspapers.

While most Quincy residents welcomed developments that made cameras easier to use and less expensive, concerns also arose about their potential for misuse. An editorial in the Quincy Daily Journal of April 2, 1896, stated: “It will be as easy to photograph the doings of our neighbors in the next room as to look out the window...there will be no privacy for anybody anywhere.” Detractors even warned of possible spirit and thought photography.

Experimenters, though, continued to transform photography from a cumbersome, expensive and often dangerous enterprise to one accessible to most citizens.

Two Quincy inventors, Henry Whipple and Loren Cox, made significant contributions in 1900 with their patented portable changing bag and darkroom. Their invention could be used in the field as well as the studio or home and allowed photographers to keep their head uncovered while shooting. This provided more mobility and ease in focusing on the subject. Major American newspapers recognized their invention and the Philadelphia Record alone gave Whipple and Cox a half column of coverage.

During World War I, the U. S. deployed aerial photography with the first airplane reconnaissance flights. Quincy native Bob Mathes, a professional photographer with a studio at 503 Hampshire, joined the Signal Corps and began wielding a camera adapted for aviation. On the home front, a local dealer estimated that Quincy residents owned 2,500 cameras and would expose 20,000 yards of photographic film during the summer and fall of 1916, for a total of 200,000 pictures. He called this phenomenon “snapshotitus,” and it continued to spread.

Soon after the war ended, Quincyans formed the city’s first Boy Scout council and, inspired by reconnaissance pilots like Mathes, it offered a merit badge in photography. Quincy High School students handled all of the photographic work themselves for their yearbook “Shadow.”

Miss Mary Beatty of the local University of Illinois Extension Office organized a photographic competition to showcase the Gem City’s architectural beauty. The Adams County Fair also launched a photographic competition and—after long being dismissed as a fad and a gimmick—Quincy’s Art Club held its first exhibit of photographic art.

Sources

“Alarming Possibilities.” Quincy Daily Journal . April 12, 1896, 8.

“Candace McCormick Reed: Reinventing Herself.” By Kristan H. McKinsey. www.historyillinois.org >Portals>Historical Society> Candace McCormick.

“Gem City Business College.” Quincy Daily Journal . March 16, 1892, 4.

The History of Photography . Margaret Vallencourt, ed. Part of the Britannica Guide to the Visual and Performing Arts. New York: Britannica Educational Pub., 2016.

“Quincy Inventors.” Quincy Daily Journal . March 10, 1900, 7.

“Snapshotitus.” Quincy Daily Whig . July 23, 1916, 11.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Dell Pub. Co., 1973.

“War Daguerrotyped.” Quincy Whig . Dec. 23, 1854, 2.