Lincoln, Douglas and the Power of Quincy’s Press

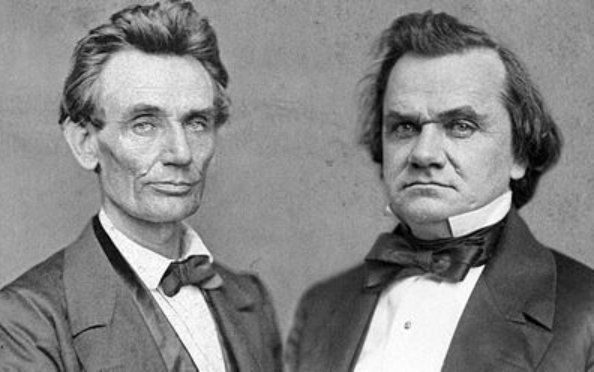

There was little either man could say that the other could not anticipate. Stephen A. Douglas and Abraham Lincoln had been debating each other for 24 years—from the day they met in early 1834 at the Illinois State Capitol in Vandalia. The 6’4” Lincoln did not think much of Douglas, who at 5’4” was a full foot shorter. On his first sighting of Douglas in the Illinois House chamber, Lincoln nudged a seatmate and said, “That’s the least man I ever saw.”

Lincoln would not disparage Douglas again. Twenty-two years later, Lincoln would write, “With me, the race of ambition has been a failure—a flat failure. With him, it has been one of splendid success. His name fills the nation and is not unknown in foreign lands.” Douglas’s political star had risen meteor-like into the heavens. Lincoln’s had stalled in the Illinois prairie.

Now in 1858, Lincoln was attempting to wrestle Douglas’s senate seat from him. After the Democratic Chicago Times , partially owned by Douglas, embarrassed Lincoln—the newspaper suggested Lincoln join a circus to attract his own audiences instead of following Douglas to take advantage of his, Douglas agreed to debate Lincoln in seven Illinois congressional districts. Douglas made out the schedule and put the sixth debate in Quincy on October 13. Quincy was Douglas’s turf. He had moved to the community in March 1841 after being appointed an associate Supreme Court justice and circuit judge there. The area’s voters in 1843 elected him their congressman. Re-elected twice, state legislators chose Douglas to become U.S senator. He had lived in Quincy for seven years.

Debates were not new to Lincoln and Douglas. What was new was the use they made of the press to extend the reach of their voices across the country. Over eight nights In Springfield in 1839, they were two of four Whigs and four Democrats to debate President Martin Van Buren’s fiscal policy. Douglas, who arranged the speeches, scheduled himself to speak first and scheduled Lincoln last. Lincoln’s talk was in the evening after Christmas. As Douglas intended, Lincoln was embarrassed by his scanty audience. He was, however, every bit as astute as Douglas. Enlisting the help of the Sangamo Journal , his speech stretched across seven columns of the newspaper’s front page. Local Whigs published the speech in pamphlet form and distributed it across the state to tout the party’s presidential candidate, William Henry Harrison. Lincoln was embarrassed once again. He chaired Harrison’s campaign in Illinois. Harrison won nationally but lost in Illinois to Van Buren, whose Illinois campaign Douglas chaired.

Like those in most communities in the 19th century, Quincy’s newspapers lined up behind political parties. The Quincy Whig kept the party’s old name despite its demise in 1855 and supported the new Republican Party, which replaced it. The Quincy Herald was the democratically oriented newspaper. In the weeks before the debate, each summoned the faithful to the debate to support their party’s candidate. Keokuk’s City Gate newspaper reported a steamboat had been arranged to ferry people roundtrip to Quincy for $1.50, supper included. Other boats brought spectators from Hannibal and other ports along the river

With both party’s arrangements committees seeking to outdo the other, the Whig bragged that the Republican “ladies, God bless them,” intended to turn out for Lincoln in a welcoming parade that would include a “number of private carriages, loaded with the fair (female) freight. . . .”

The Whig on October 11 charged that Douglas had mortgaged some Chicago property for $52,000 to “Fernando Wood, the notorious Tammany Hall politician of New York.” Douglas, the Whig said, was buying crowds to manufacture enthusiasm. Contrasted with that, enthusiasm for Lincoln, said the Whig , “comes spontaneously from the hearts of freemen.”

The Herald sought to recover press momentum by pointing out that while Henry Clay was often credited with the Compromise of 1850, which settled the issue of slavery in the huge land mass Mexico ceded to the United States after the Mexican War, it was actually Quincy’s Douglas who won the passage of every bill to achieve the Compromise of 1850. Clay tried for months but had been unable to do so.

After stops in Augusta and Camp Point, Douglas was scheduled to arrive in Quincy by train at 9 p.m. October 12, the day before the debate. The Herald encouraged Democrats to meet at the courthouse on the square at 8 p.m., where a procession would march to the railroad depot near the riverfront “to extend to our distinguished Senator a hearty and enthusiastic welcome.” The Whig that same day reported that Lincoln would arrive the next morning and detailed the procession that Chairman Abraham Jonas arranged for him.

On debate day, Lincoln was introduced at 2:30 p.m. and Douglas at 3:30. At each debate, the sole issue was slavery. Some historians describe this sixth debate at Quincy as the nastiest of the seven. Lincoln, they said, took the gloves off. He attacked Douglas for never saying slavery was immoral or wrong. He also struck out at his own Republican listeners who did not do so: “If there be any man who does not believe slavery is wrong. . .that man is misplaced, and ought to leave us.”

Douglas responded that he could not logically argue whether slavery was right or wrong. The constitution gave “each state the right to do as it pleases on the subject of slavery. In Illinois, we have exercised that sovereign right by prohibiting slavery within our own limits. I approve of that line of policy.”

When Illinois legislators met on January 5, 1859, to select a U.S. senator, they voted 54 to 46 for Douglas. Lincoln lost that race, but his anti-slavery messages of 1858, relayed by the press across the country after 1858, opened the doors to the White House to him instead of Douglas in 1860.

Sources

“$52,000 for Douglas!” Quincy Daily Whig, October 11, 1858, 2.

Reg Ankrom, Stephen A. Douglas: The Political Apprenticeship, 1833-1843. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Press, 2015, 4.

Joseph Barrett, Life of Abraham Lincoln. Cincinnati: Moore, Wilstach, and Baldwin, 1864 54.

“The Friends of Hon. Abraham Lincoln.” Quincy Daily Whig, October 13, 1858, 3.

“General Stephens repudiates the Stinkfingers.” Quincy Daily Herald , October 15, 1858, 2.

Harold Holzer, ed., The Lincoln-Douglas Debates: The First Complete, Unexpurgated Text. New York Harper Collins, 1993, 277-280.

Holzer, Lincoln and the Power of the Press: The War for Public Opinion. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2017, 143.

“Reception of Judge Douglas in Quincy.” Quincy Daily Herald, October 11, 1858, 3.

Tom Reilly, “The Press and the Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858.” Institute of Education Sciences, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED159708

Saul Sigelschiffer, The American Conscience: The Drama of the Lincoln-Douglas Debates. New York: Horizon Press, 1973, 329, 342, 336.

Edwin Erle Sparks, The Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858. Springfield: Illinois State Historical Society, 1908, 391-393.

Joshua Speed, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln and Notes of a Visit to California. Louisville: John P. Morton and Company, 1884, 24-25.

“The Two Processions.” Quincy Daily Whig, October 16, 1858, 2.