Education of a pioneer woman physician

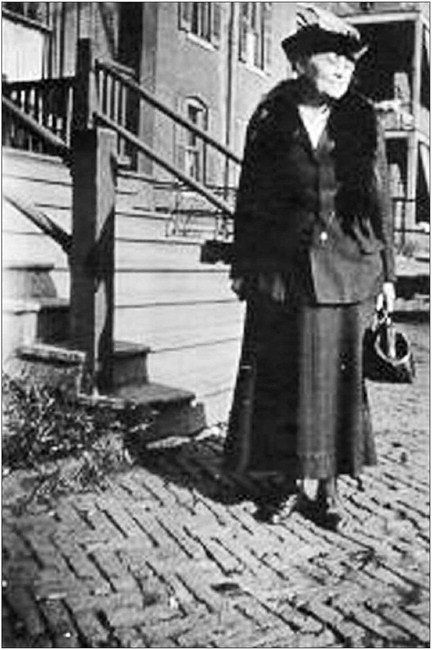

Dr. Melinda Knapheide Germann (1862-1953) described herself as “one of the early pioneers of woman physicians in Quincy. To prove my loyalty as a citizen of this city, I was born, reared, and enjoyed the advantage and the many opportunities that Quincy offered.”

Melinda Knapheide graduated from Quincy College of Medicine in 1886. Shortly after graduation she made the first of two trips to Europe for further medical education. She began her practice as a single woman and married a local pharmacist, Henry Germann in 1891. After joining the staff of Blessing Hospital in 1901, she taught obstetrics to the nursing students from 1906 to 1936. She presented a scholarly paper to the American Medical Association Convention in 1907, one of the few Quincy physicians to do so. In addition to her family and her busy medical career, she was the first woman elected to the Board of Education, serving from 1912-1929. She was also the first woman elected to the Board of Supervisors in 1917. In 1938, Dr. Germann wrote a short memoir, “The Reminiscence of a Pioneer Woman Physician” recounting her training in Europe in the late 1880s and other highlights of her long career. Both of her children, Dr. Hildegarde Germann Sinnock and Dr. Aldo Germann, became practicing physicians at Blessing Hospital.

Though her memoir discusses many parts of her career in Quincy, one of the more intriguing sections recounts her post graduate medical education in Europe. After a few brief sentences on her youth, she began to write about her medical life. Saying: “ You may wonder why I selected a professional career. In those days few women took an active interest in affairs outside of their household duties. I owe much to my parents for their good judgment and foresight. Their ideas were that their daughters should have a profession or business by which they could be financially independent…. I decided to study medicine. ... (I) entered the Quincy College of medicine, which later became a department of Chaddock College. We numbered fourteen, eleven men and three women. After receiving my diploma from this school I decided to further my studies in medicine abroad. Through the Methodist Travelers in New York City, we found a suitable companion to accompany me across the water, and I accordingly left Quincy the early part of April and sailed on a Netherland steamer, arriving in Amsterdam, Holland. My voyage was very thrilling and exciting, especially when the ocean was rough. I had always thought that I would be a good sailor, but experience taught me differently. ”

She had a good educational experience in the Medical Department of the University of Zurich and appreciated being treated equally to men. Knowing German was to her advantage in class, with physicians, and with patients. She stayed one year and then went to Vienna where her experiences were not as pleasant. She did not like the inequality between the men and women students and the limitations on which classes women could take. Nor did she appreciate the way the patients were treated. She wrote, “Patients coming for examination and treatment were treated, not as human beings, but as so much material. This condition often aroused my sympathy as well as my indignation. The nurses too in the hospitals and clinics were not treated with civility due them.”

After six months in Vienna, she headed to Paris to continue her studies. “I shall never forget the difficulty I experienced with the custom house officials there. I had studied some French while in Zurich and could read fairly well, but when it comes to carrying on a conversation I was at sea. I of course opened all my baggage, but I could not understand the officials and they could not understand me. Finally one of them began to talk German, after which we got along famously.”

Fortunately, the difficult experiences in Vienna were not repeated in Paris. She appreciated the respect for patients as she said: “My first month there, the semester not having started, I spend taking daily lessons in French and attending a children’s clinic. The assistant, whom I accompanied on his bedside rounds, could not speak English and wanted very much to learn the English language and I was equally anxious to learn the French. We both spoke German, so we had very interesting trips, in medicine as well as in the two languages. Here as in Zurich men and women were on an equal basis, and I matriculated as a student in the University of Paris. The material here was likewise abundant, but women patients were treated with more respect than they were in Vienna. The nurses here like those in Vienna were not the high type of the present day American nurse. However, they were shown more courtesy and consideration then those in Vienna.”

Finishing her six month course in Paris, Dr. Germann was ready to return to America. She says, “On reaching the steamer I went on board, took one more walk, one last look and in my head bid good bye to Europe. My voyage home was pleasant and uneventful. The sea for the most was calm and I certainly was happy when we steamed into New York Harbor with the Goddess of Liberty welcoming me home.”

As soon as she returned to Quincy she began her life as a physician but many years later Europe again beckoned and this time she took her family along. They went to Paris and Zurich ending their trip in Vienna where she stayed to take some classes.

She wrote, "Conditions here had changed somewhat. In speaking of the changes which had taken place in Vienna since my first visit, I must not forget to mention that in 1894 the American Medical Association of Vienna was organized by 35 English speaking physicians. In 1915, when I made my second visit to Vienna, its membership had reached two thousand.” Many years later when speaking about her education she said, “You may ask what was the attitude of the men students toward women? I must say that I was always treated with the utmost courtesy both here and abroad.” Dr. Germann practiced medicine in Quincy for over 50 years and ended her narrative memoir by saying: “In conclusion let me say that the science of medicine is a great art. Research and study continue on the march. The different medical organizations including the county, state and nations have placed it on a very high place, and their aim is higher still. Within the last few years the requirements for study, as well as the time spent in study, have been increased, hospital internship made obligatory and state board examinations required. My work as a physician has always been a great joy to me even though I missed many of the social pleasures that my friends indulged in. It is true I encountered many hardships and being a wife and mother I had other responsibilities which were too dear to give up. At the same time there were occasions when it was difficult for me to decide where my duty was, my family or my practice. I came through safely and I have never regretted that I selected the practice of medicine as my life work.”

Arlis Dittmer is a retired medical librarian. During her 26 years with Blessing Health System, she became interested in medical and nursing history — both topics frequently overlooked in history books.