Timothy Rogers: Patron of 'Pucker' Street

The bust of early Quincy settler and entrepreneur Timothy Rogers is embedded at the top of a 40-foot marble tower on South Fifth Street. The four-sided tower embellished with ornamental wreaths is anchored on each side with the bust of Rogers. The imposing and handsome family vault is testimony to one settler’s story of business acumen and good fortune.

The extraordinary vault built in 1876 with space for 112 caskets is a cornerstone monument at Woodland Cemetery at 1020 S. Fifth. The doors are of solid marble with inside doors made of iron slats. The marble, shipped from Vermont, filled 12 freight cars, each carrying 20,000 pounds.

The vault was built 38 years after Timothy Rogers had made a remarkable business, civic and personal mark on the city he called home for more than 50 years. His enterprising business influence on development in the central core of town at Sixth and Hampshire was notable.

In the first years of settlement beginning in 1825 Quincy didn’t have much to offer except potential. The population grew slowly in the first dozen years with settlers trickling into the marshy, disease-ridden Mississippi Valley. In spite of primitive roads, buggy hotels, and less than fine food, the city grew at a more rapid rate during the nationwide financial crisis of late 1830s when settlers sought better opportunities. When Rogers arrived in 1838, Hampshire Street was but a ridge two blocks long, called “Pucker Street” and was the only level traveling route east from Quincy. In 1838 there were just over 1,200 residents in the village and by 1840 approximate 2,600 claimed Quincy as home. The city was incorporated in 1840 and the first municipal laws were entered on the books fifteen years after it was founded.

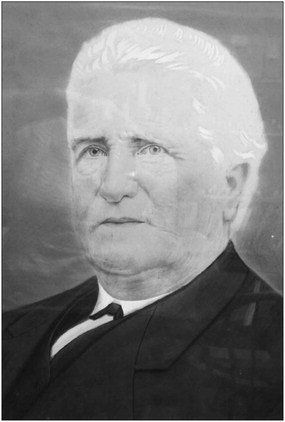

This was the unstable environment that Timothy Rogers came to in 1838. Born, raised and married in Connecticut, 30-year-old Rogers with his small family undertook the journey to the frontier. Rogers was born in 1809 in Vernon, Conn., in Tolland County and married Dorothy M. Billings in 1832.

Experienced in carriage and wagon making, Rogers quickly found work building wagons. Within two years he purchased the wagon business from his employer and in 1847 joined Charles H. Winn, a fellow wagon master, to form the firm of the Rogers & Winn Wagon Co. The partnership was one of the earliest local wagon making businesses, located first on Fifth Street between Maine and Hampshire just north of the first Adams County Courthouse. Production was soon moved to the east side of Sixth Street between Maine and Hampshire and Rogers lived on the west side. The partnership thrived and was said to be “second to none” in the West during this time. After several productive years Rogers bought out Charles Winn in 1854 and built a new three-story building at the same location on the east side of Sixth with other buildings on the west side. By then Rogers had acquired considerable wealth in the 16 years since his arrival. He produced wagons and agricultural implements, primarily plows.

By 1855 Rogers employed 35 to 40 men year round and produced 800 wagons valued at $60,000 and 1200 plows worth $8,000. He was in competition with about 20 other leading wagon makers. Rogers handed over the operation of the extensive business to his sons, William T. and Edward A., in 1864 and retired from the management end of the business. He was 55 years of age.

A few years earlier, Rogers had already begun an occupational change. In 1860 the man who had worked and lived at Sixth and Hampshire almost since his arrival had taken on another position on the north side of Hampshire just steps from his wagon firm. He became proprietor of the Adams House, a newly named hotel on the north side of Hampshire between Sixth and Seventh streets owned by Henry Hess. In 1856 Rogers had loaned Hess $40,000 to remodel and enlarge the hotel. The investment in today’s dollars would be worth approximately a half million dollars. The “new” hotel was four stories high and 80 feet across the front with iron balconies across the front on the second and third floors allowing visitors outdoor promenade access.

The Adams House, formerly the Hess House, opened on May 29, 1860. An 1862 newspaper story related an anecdote from the Hannibal Messenger that a Mr. Frazee stated his stay at the Adams House had been met by the “prince of clever fellows,” Rogers, who could “burn, brown, singe, fry or griddle a steak to the satisfaction of any man ...” He further commented that although Rogers was a “Lincoln man,” he was very obliging. Familiar hotel patrons affectionately called the good humored Rogers, “Uncle Tim.”

Rogers took over the hotel in 1870 when Hess was unable to meet his debt and did some additional remodeling. The Adams House was renamed the Occidental Hotel. Advertisements in the fall of 1870 indicated that after a year-long renovation the hotel was “now the largest in the city.”

Rogers and his wife would call the fashionable hotel home for nearly 30 years.

With an increasing demand for wagons and manufacturing space the sibling partnership built an additional factory at Fourth and Oak Streets in 1871. The next year on April 26, 1872, a massive fire wiped out the Sixth Street wagon shops as well as other adjacent buildings on Sixth Street.

Rebuilding was immediate and on a large scale. By August that year new construction was underway on a signature edifice on the southeast corner of Sixth and Hampshire. The ground floor was finished and plans indicated no expense was to be spared. Roger’s new elaborate undertaking was a mammoth four-story stone and brick structure that contained storerooms and offices plus a public hall on the fourth floor. It was divided into two sections and there were six entrances, on Hampshire, Sixth Street and in the rear. Inscribed on the pediment front surmounted with an imposing base and scrolls the designation of “Roger’s Block” spoke to the enormity of the enterprise. The Post Office was housed in the building for several years.

Timothy Rogers also owned the “Rogers Flats” on the west side of 6th Street and many other tenements and business buildings. During his years of business activity he accrued considerable wealth that was partially “expended in improvements of lasting benefit” to the city.

Timothy and Dorothy Rogers had six children, four of them born in Quincy. Two daughters and a son died when they were roughly a year old in 1838, 1842, and 1852. The older sons, William and Thaddeus, were born in Connecticut. Edward was born in Quincy in 1845. The couple’s three sons contributed widely to the city’s business, civic and cultural welfare.

William T. Rogers, prominently identified with city business interests, became active in public affairs around 1876, served on city council for two years and was elected mayor in 1878. Mayor Rogers served two years before he died in office on April 12, 1880, at the age of 64. Thaddeus, known as a scholar, philosopher, traveler and writer, attended the University of Heidelberg in Germany, studied and practiced law for a time in Quincy, owned a publishing house at 520 Hampshire and published a local newspaper, the Quincy Daily News. He died at the age of 63 on Dec. 7, 1898. A month previous to his death he held a dinner party at his home in commemoration of the 60th anniversary of his arrival in Quincy.

Edward, known as “Ed,” died on Nov. 1, 1909 in his home at 1627 Maine Street. The Rogers families owned acreage and a stock farm in Fall Creek Township where Edward in particular spent a “good deal of time” tending the farm work.

The Quincy patriarch Timothy Rogers was 80 years old when he died on Jan. 6, 1889, and was buried in the family vault he had constructed some 13 years previously. As was the common custom of the time his funeral was held in his home, the Occidental Hotel. Dorothy Rogers’ funeral in November 1892 was also held at the hotel. Timothy Rogers had lived and worked in the confines of Sixth Street and Hampshire for 50 years.

Iris Nelson is reference librarian and archivist at Quincy Public Library, a civic volunteer, and member of the Lincoln-Douglas Debate Interpretive Center Advisory Board and other historical organizations. She is a local historian and author.