Elijah Lovejoy and Quincy abolitionists

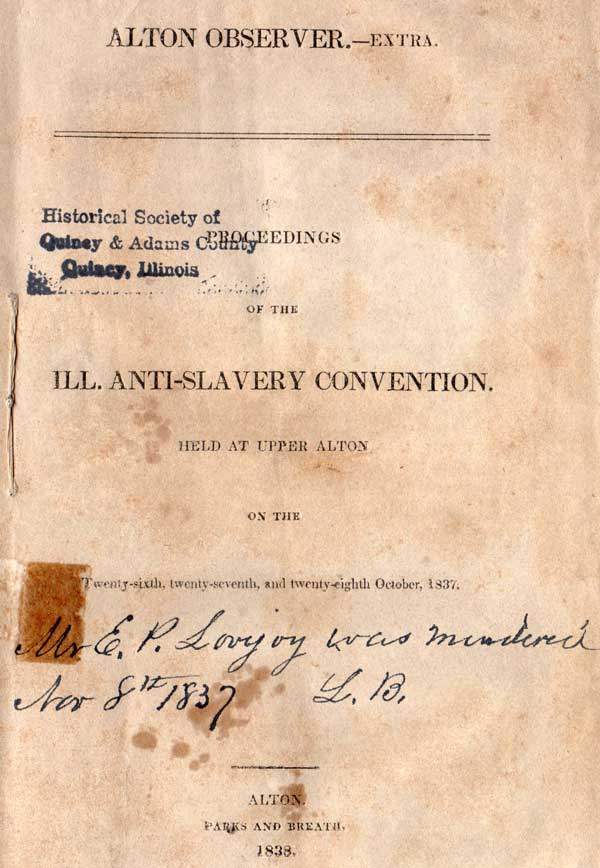

Among the artifacts of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County is an original copy of the "Proceedings of the Illinois Anti-Slavery Convention" held in Alton Oct. 26-28, 1837. Only 10 copies of the 36-page booklet, published as an extra of the Rev. Elijah Parish Lovejoy's abolitionist newspaper, the Alton Observer, are known to exist.

The document was a gift of Christiana Holmes Tillson to the Historical Society in 1897, one year after the Historical Society was founded. Tillson was the wife of John Tillson, a New Englander who came to Illinois in 1819 to speculate in land. The couple was connected to another land speculator by virtue of the marriage of their son John Jr. to Ann Wood, the daughter of Quincy founder John Wood and Ann Streeter Wood.

Lorenzo Bull, president of the Society in 1897, scrawled a simple, sublime note across the front page of the booklet.

"Mr. E.P. Lovejoy was murdered Nov. 8th, 1837," he wrote.

Bull's notation was off by a day. Lovejoy had been killed Nov. 7.

The Tillsons knew Lovejoy well. Lovejoy had stayed with them at their home in Hillsboro when he arrived in Illinois from Maine by way of New York in 1827. It was the largest home in Montgomery County, a reflection of Tillson's success at speculating in land in the 3.5 million-acre Illinois Military Tract. By the time he had finished that work, which brought him to Quincy in 1831, Tillson owned 2,651 quarter sections--or 424,160 acres.

Lovejoy hoped that in Hillsboro he would be able to leverage his college degree and five years experience for a teaching post. But Hillsboro in 1827 had no need for pedagogues. Lovejoy moved on to St. Louis, where he found a teaching position.

Lovejoy's father Daniel was a Presbyterian minister. Daniel named his first son Elijah Parish to honor the Congregationalist minister with whom he stayed during his own education for the ministry in Massachusetts. Despite that legacy, Elijah Parish Lovejoy lost his religion in St. Louis. After five years there, the distressed young man wrote his parents that he felt he was "a more hardened sinner than ever." He grew increasingly despondent over his religious infidelity.

That was until he heard the Rev. Dr. David Nelson, himself a converted infidel and now powerful Presbyterian preacher. Lovejoy attended Nelson's two-week revival in St. Louis's First Presbyterian Church in January 1832. Nelson converted the skeptic, and in February Lovejoy informed his parents that he was on his way to Princeton to enter studies for the ministry.

The Anti-Slavery Convention in Alton in October 1837 reunited Lovejoy and Nelson, a member of the Quincy delegation. Nelson had experienced pro-slavery wrath in Missouri the year before. In May 1836 he had been driven out of Palmyra by a pro-slavery mob. He had chosen Palmyra to make his life's work the creation of Marion College, an abolitionist institution in a state where the institution of slavery lived. Driven out by threats of death, Nelson had found refuge in Quincy.

Having noted that Adams County in August 1835 established an anti-slavery society, the first in Illinois, Lovejoy for several months in 1837 called for a statewide organization to emulate it. The Adams County society's constitution condemned the "awful sin of slavery as sanctioned by the laws . . . in direct violation of the Laws of God . . . ." It was the object of Adams County's society to abolish slavery in the United States and to "elevate the character and condition of the People of colour by encouraging their intellectual, moral, and religious improvement, and by doing away with Public Prejudice against them."

While denouncing prejudice against blacks, the Adams County society's founders encouraged participation by women. By the time of the convention at Alton in 1837, 39 of the society's 131 members were women. Officers of the society were Henry H. Snow, president; Dr. Richard Eells, vice president; and Willard Keyes, secretary and treasurer. Snow and Eells were well known for their abolitionist sentiment. Snow was an active member of the Rev. Asa Turner's abolitionist Congregational Church at Fourth and Jersey. Eells was known to have harbored fugitive slaves. Keyes was little known for public pronouncements. He was as private in character as his partner John Wood was public. But Keyes abhorred slavery.

Not all Quincyans were as fervent in that sentiment. State Sen. Orville Browning of Quincy took a contrasting view. He delivered a committee report to the General Assembly in 1836 branding abolitionists dangerous to the Union, adding that anti-slavery activities had not helped slaves and only stirred discord between North and South.

Of the 245 Illinois men who signed the petition for a statewide anti-slavery convention, 61 were from Quincy and 10 from Fairfield, today's Mendon. Seventeen would attend the meeting in Alton when it convened on Oct. 26, 1837.

On that day Lovejoy called the statewide convention to order and delegates elected as chairman the Rev. Gideon Blackburn, Blackburn College founder at Carlinville that year. Lovejoy had added to the convention agenda a statement that was destined to create problems from the start. Noting that three of his newspaper's presses had been destroyed, he called for a discussion of the right of free speech, without which he feared the spirit of freedom in the United States would be extinguished.

That addition brought to Alton 107 pro-slavery conventioneers, led by Illinois Attorney General Usher P. Linder of Charleston. Although claiming to be advocates of free speech, their purpose was to disrupt the convention. Because they made up the assembly's majority, the dissidents had the ability to control the convention. A sagacious Blackburn appointed Linder, Illinois College President Edward Beecher of Jacksonville and Quincy Congregationalist Minister Asa Turner -- the latter two known abolitionists -- to create a report on "use" of the convention.

Beecher and Turner returned a majority report favoring anti-slavery speech, but Linder insisted that his minority resolutions be read, and they were adopted. To take back their hijacked convention, anti-slavery delegates, with support of the pro-slavery delegates, approved a non-debatable motion to adjourn without a date for a future meeting.

While their opponents drifted out of Alton, the anti-slavery men reassembled at different locations the next morning and quickly approved the creation of the Illinois Anti-Slavery Society.

The strength and spirit of the Adams County delegates' abolitionism resulted in their filling nearly every seat of the new society's leadership. Henry Snow was elected a vice president and Quincyans Rufus Brown, Richard Eells, Ezra Fisher, Joseph T. Holmes, Willard Keyes, Asa Turner and William Kirby of Fairfield (Mendon) filled the seats of the Board of Managers.

Lovejoy's Quincy friends remained loyal to him. When they learned some Alton leaders blamed Lovejoy for the continuing mob action in Alton, Quincy abolitionists repeatedly urged Lovejoy to move his press to their town upriver. Quincyans, they assured him, would protect him and his press.

Lovejoy, however, was encouraged by a meeting of the Springfield Presbyterian Synod in October, which endorsed Lovejoy and his newspaper's actions. He chose to stay in Alton.

During the evening 11 days later--after Lovejoy had witnessed the fruition of his plan to create an Illinois Anti-Slavery Society--a mob moved in on the Godfrey-Gilman Warehouse in Alton. That morning, Lovejoy friends had moved inside the block-long building Lovejoy's fourth press, which had been delivered by the "Missouri Fulton" steamboat at 3 a.m.

Members of the mob placed a ladder against the building, planning to set the wooden roof on fire. Lovejoy rushed outside to push the ladder away. He took three shots in the chest, two in the stomach and one in his left arm. He struggled to get back inside.

"My God, I am shot," he said.

"They have murdered Elijah Lovejoy," someone from inside the warehouse yelled.

The mob outside erupted in shouts of joy.

Reg Ankrom is executive director of the Historical Society. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

THE ADAMS COUNTY 17

Below are the names of the 17 Adams County men who attended the convention in Alton in October 1837 to create an Illinois Anti-Slavery Society, modeled on the 1835 Adams County Anti- Slavery Society, the first in the state:

Amos Andrews, Erastus Benton, Rufus Brown, W.P. Doe, Willard Keyes, E. M. Leonard, the Rev. Dr. David Nelson, H. Pitkin, Jireh Platt, C. Robbins, Henry H. Snow, the Rev. Asa Turner, Levi Stillman, G. Thompson, Robert Vance and George Westgate (all of Quincy) and William Kirby of Fairfield (Mendon).

Sources

Beard, Cecil K. A Bibliography of Illinois Imprints, 1814-1858. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966.

Blackwood, James. Quincyans and the Crusade Against Slavery: The First Two Decades, 1824-1844. Quincy, Illinois: Blackwood Enterprises, 1972.

Dillon, Merton L. Elijah P. Lovejoy, Abolitionist Editor. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1961.

Journal of the Senate of the Tenth General Assembly of the State of Illinois at Their First Session. Vandalia, Illinois: William Walters, 1836.

Lovejoy, Joseph C. and Owen. Memoir of Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy. Reprint, Freeport, New York: Books for Libraries Press, 1970.

Magoun, George Frederick. Asa Turner: A Home Missionary Patriarch and His Times. Boston: Congregational Sunday-School and Publishing Society, 1889. Reprint, Boston: Harvard Book Store, 2012.

Muelder, Hermann R. Fighters for Freedom: A History of Anti-Slavery Activities of Men and Women Associated with Knox College. New York: Columbia University Press, 1959. Reprint, Knox College, 2005.

Preamble and Constitution of the Adams County Anti-Slavery Society. File MCA, Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

"Proceedings of the Ill. Anti-Slavery Convention Held at Upper Alton." Alton Observer Extra. Alton: Parks and Breath 1838. File D379, Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

Richardson, William A. Jr. "Dr. David Nelson and His Times," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Vol 13. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Historical Society, 1921.

Reynolds, David S. Waking Giant: America in the Age of Jackson. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2008.

Simon, Paul. Freedom's Champion: Elijah Lovejoy. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1994.

Syoung Park, "Land Speculation in Western Illinois Pike County, 1821-1835," Journal of the Illinois Historical Society. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Historical Society, Summer 1984.

Tanner, Henry. The Martyrdom of Lovejoy: An Account of the Trials & Perils of Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy. New York: Augustus M. Kelley, Publishers, 1971.

Tillson, Col. John Jr. History of Quincy, in William H. Collins and Cicero F. Perry, Past and Present of the City of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1905.