Eliza Browning: Outspoken yet respected

In the mid-19th century when refined ladies were not outspoken, a well-known Quincy lady extended her voice and influence beyond the private sphere and into the political arena.

Eliza Caldwell Browning had arrived in 1836 as the new wife of leading citizen and lawyer Orville Browning. She was a politically conscious woman throughout her life. Depicted by scholars as a woman of intelligence and commanding presence, she was a respected adviser of men who ordinarily spurned the brains of women.

Eliza Browning spent most of her life in the midst of Illinois politics. She was born in Kentucky near Richmond in October 1807, the 14th child of Maj. Robert and Hannah Willis Caldwell. She grew up about 25 miles south of Lexington, Ky., and was educated in the bustling city, known as the "Athens of the West," in one of its fine academies for young ladies. At the age of 28 Eliza married Orville H. Browning, 30, on Feb. 25, 1836, in Richmond and left Kentucky for Illinois. Browning, a native of Kentucky, settled in Quincy in 1831 and had returned to Kentucky to marry.

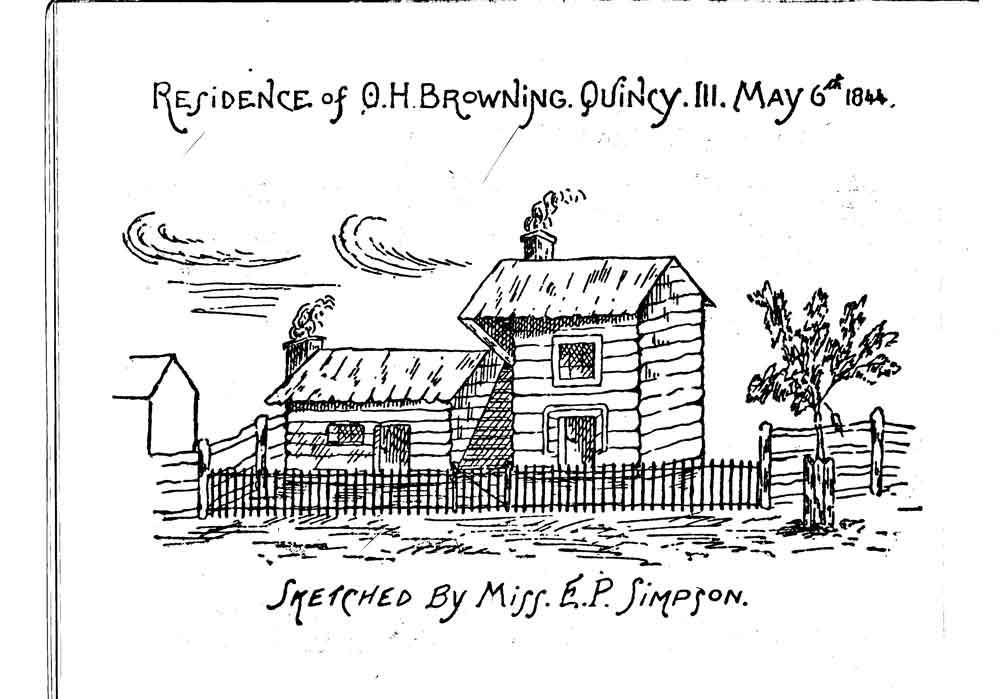

When Eliza came to Quincy she lived in a tiny log cabin on the site where the Brownings would later build an impressive mansion. The village had grown to a population of about 1,650 and had 25 stores. Quincy had become a center of frontier Illinois politics. As the largest hub on the northern Mississippi River, the busy harbor facilitated steamboat travel, readily accommodating trips to St. Louis and Kentucky.

Within a year of their marriage Orville Browning was elected to a term in the Senate when the state house was in Vandalia. During the following few years Eliza met governmental officials she would know the rest of her life and had a particularly close relationship with legislator Abraham Lincoln. During the legislative winters, Eliza and Lincoln spent evenings and leisure time together in the Brownings' quarters when they boarded at the same house.

During these Legislative sessions Vandalia was a center of society with guest lecturers for candlelight presentations and dances on the public square. One participant referred to the season as a time of "intellectual feasts." Eliza brought more than the conventional conversation to the environment and was appreciated for her candor and intelligence. Legislator Usher F. Linder described her further as an "elegant and accomplished lady." She was tall and dignified with a charming personality, a good sense of humor and a self-assured manner.

Eliza spent two winters in Vandalia. When the new opening session in Springfield convened in 1839, a cotillion ball was to be held at the elegant home of legislator Ninian Edwards. Legislators Abraham Lincoln and John Hardin wrote a tongue-in-cheek letter to Eliza, encouraging her to come to the new capital before Christmas Day. Her husband, the writers assured her, "will be considered ... as the minor party of the Quincy delegation."

William Butler had offered the use of his parlor, and with Eliza present, "there would be extensive improvements" in "visiting, conversation & amusement." Two other legislators joined Lincoln and Hardin as signers of an invitation dated Dec. 11, 1839, in solicitation of Mrs. Browning's company.

In a parody on legal petitions, a portion of the printed invitation addressed to "The Honorable Mrs. Browning" reads: "We, the undersigned, respectfully represent to your honoress that we are in great need of your society in the town of Springfield and therefore humbly pray that your honoress will repair forthwith to the seat of Government ... ."

The distortion of legal language used in the invitation indicated that the recipient would appreciate the parody. The invitation allows a warm glimpse of these politicians socially and regard extended to women of a more thought-provoking caliber. Eliza's response plays off their parody with an equally lofty reply dated Dec. 20 addressed to J.J. Hardin, J.S. Dawson, E. B. Webb and A. Lincoln. The playful but straightforward letter begins: "I fully appreciate the … polite invitation to resume my high, and distinguished, station at the seat of government; and I am perfectly aware that your talented Legislative body, will find great difficulty in getting the important business before them without the aid of my Honoress. And I am happy to find that you justly appreciate the Wisdom, Judgement, and brilliant talent that has ever marked my course."

The letter goes on to refer to the new seat of government in Springfield, where Lincoln and Browning both boarded at the home of William Butler. Eliza sardonically cautions, "You all are at Mr. Butler's enjoying Mrs. Butler's good things, living on the fat of the Land: the State house most finished; your feet have been taken out of the mire clay of Vandalia and placed on the beautiful mossaick [sic] pavements of Springfield." Referring to the $50,000 promised for internal improvements that Springfield pledged in order to move the seat of government from Vandalia to Springfield, Eliza follows with, "The bargain has been complied with I suppose and you all are enjoying the full benefits of it. I say what will you do for your starving beloved people?" Eliza ends her letter saying, "I digress somewhat gentlemen from a formal reply to your polite invitation, but I hope you will pardon me as I feel anxious to aid you by a few hints as I cannot by personal counsel." Even though Eliza was a woman and therefore disenfranchised, she kept abreast of political maneuverings and was outspoken about legislative decisions.

Eliza was known for her sharp delivery of opinion. She did not hold back either praise or criticism and as Lincoln biographer Albert Beveridge states Eliza was "not only powerful socially, but influential in politics." A letter from Edward D. Baker on Feb. 1, 1844 indicates an instance when her influence was requested for the best interest of the party. The letter begins, "My Dear Madam, I have been so used to your brilliant persecutions that I heard of your expression of some slight degree of interest in my political fortune with great astonishment." Baker goes on to state, "You see in this "talk" that I commune very freely with you upon subjects not always committed to paper. I am sure that from Mrs. Browning in her candid moods -- I have no reason to fear misconstruction." The letter requests a reply if she is in agreement with his position and if she has a contrary opinion, he states, "I can only implore the charity of your silence."

Responding to tactics being used in Lincoln's 1860 promotion for President Eliza wrote to Illinois Secretary of State Ozias Hatch: "I fear fence rails nor the low ‘Slang Name' of Old Abe will not do it; but the Hon Abram Lincoln with the hearty efforts of all good Republican(s) ... will do it." An irritated Eliza voiced her opinion about the folksy campaign slogans. As shown in an article entitled, Lincoln's Loyal Confidante published in the Journal of Illinois History, Eliza and Lincoln maintained a close relationship until his death in 1865.

How unusual was Eliza's voice in mid-19th century politics? Well educated and talented women found no place for their ambition in the public realm. During the decades of the 1840s and 1850s women had begun to speak out about their right to vote, no longer content to be disenfranchised. It is unknown if Eliza was involved in the movement.

The Quincy Daily Whig stated when Mrs. Browning died in 1885, "Perhaps no lady in Illinois was more generally known by citizens than Mrs. Browning."

Her obituary in the Quincy Weekly Whig stated that Browning had "achieved a national reputation" and formed the acquaintance of "many distinguished men who valued and acknowledged her friendship."

Eliza Caldwell Browning is buried alongside her husband and her two foster children at Woodland Cemetery in Quincy.

Iris Nelson is reference librarian and archivist at Quincy Public Library, a civic volunteer, and member of the Lincoln-Douglas Debate Interpretive Center Advisory Board and other historical organizations. She is a local historian and author.

Sources:

Nelson, Iris. "Eliza Caldwell Browning: Lincoln's Loyal Confidante, Journal of Illinois History (104): 2006, 35-76.