Ellington Township soldier honored for Civil War battle bravery

John Cook, a 43-year-old market gardener, and his wife, Ann, along with their five children, ranging in age from 3 months to 10 years, left London for the United States and arrived in New Orleans on April 10, 1845. From the Crescent City, John led his family directly to Adams County, where he purchased 40 acres in Ellington Township.

Here, John's family thrived. By the late 1850s, his two older sons Reynard and James established a wagon business, and they were soon joined by brother John Henry. The Cook family by "unswerving integrity and zealous industry" had become respected members of the county.

Whether one was a recent arrival, had been here for years, or was part of a family that went back generations, all watched as the slavery issue tore at the nation's social and political fabric. On June 16, 1858, Abraham Lincoln succinctly said, "I believe this government cannot endure, permanently, half slave and half free."

With his election to the presidency, the threat of secession became reality when the Southern states left the Union. War followed when the newly created Confederacy attacked Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861.

Reynard Cook answered Lincoln's call for men on April 29, 1861, enlisting in the 10th Illinois. He would later join the 15th Wisconsin, becoming a company captain, but resigned because of ill health in January 1863.

John Henry Cook, 22, volunteered on Aug. 14, 1862, in what became Company A, 119th Illinois Infantry. When the regiment organized, he was made a corporal but was soon promoted to sergeant.

The 119th mustered into federal service in Quincy on Oct. 10, 1862. The regiment was soon ordered to Tennessee, where in December, two companies were captured by raiding rebel cavalry. Nonetheless, for the next 16 months, the 119th continued guarding depots and railroads -- not an environment for a soldier to gain glory and honor.

In January 1864, the 119th's role changed, and the regiment began seeing limited action. By March, the 119th was part of a combined army/navy force moving up the Red River to Shreveport, La. Generals Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman and the campaign's commander, Nathaniel Banks, all opposed the operation, but as commander in chief, Lincoln insisted it be undertaken.

Further irritating Banks was the 10,000-man detachment sent by Sherman to beef up his force. When Banks laid eyes on Sherman's misfits, he shook his head and said, "I asked Sherman for 10,000 of his best men and he has sent me 10,000 damned guerillas." To Banks, these men, especially the 119th Illinois, were an undisciplined and unmilitary lot, and he was now saddled with them. Commanding this unruly lot was Gen. Andrew Jackson Smith. His men were now known as "Smith's Guerrillas."

With the water from the spring rains receding, Banks' expedition slowly moved up the Red River. While the navy worried that dropping water levels would trap the gunboats, the situation abruptly changed for the army. On April 8, 40 miles below Shreveport, the rebels struck and defeated the Federals at the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads.

That night, Banks retreated to a line held by Smith's divisions. Sgt. Cook explained that on the morning of April 9 the 119th was "in the woods on extreme left," and he had been "detailed as a clerk at headquarters...."

He recalled that "the thought of being a noncombatant was distasteful, and so, arming myself with a Sharps rifle, I took my place as sergeant in the rear of my company. I was without canteen, haversack . . . only a good big plug of tobacco, my rifle and forty rounds."

Having beaten the bluecoats the day before, the rebels struck again, and initially they were on the way to another victory. However, Gen. Smith saw a chance to redeem the day and hit back. From being on the verge of victory, the rebels suffered a resounding defeat.

Cook recounted his part in the fight. "There was nothing left to stop the cyclone now but ‘Smith's Guerrillas,' and it seemed that we . . . were to be flanked and the whole army bagged. A sickening feeling came over me as I took in the situation."

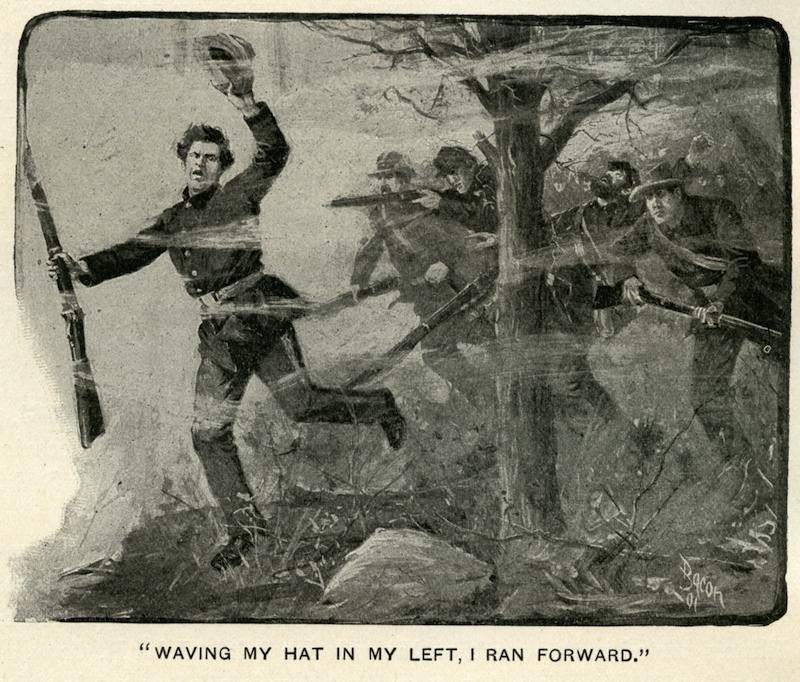

With Cook leading, and even though outnumbered, the 119th charged the enemy. "Advancing under a heavy musketry fire," Cook stated, "I turned back to cheer on the boys, when I saw John McIntyre (a Mendon soldier) . . . throw up his left hand and fall forward. I ran back to him and saw that he had been instantly killed. Then I was mad clear though."

In a rage, Cook ran forward again, firing his weapon. The rebels now focused on him. Cook wrote that one bullet went through his hat; another through his coat sleeve; and one so close to his cheek he could feel the heat. But he added, "I cared nothing for life or death -- I was in to stay."

Having "rushed into the open field and by his shouts and cheers," Cook's act of valor helped bring victory from what seemed inevitable defeat. His action not only rallied the 119th but also the whole Union line, which advanced, driving off the enemy.

After the victory at Pleasant Hill, Banks ended the Red River campaign. The navy transported the Union troops back down the river, and by early June the 119th was back at Memphis.

With the Civil War's end, John Henry Cook followed a winding path away from Adams County. For a number of years he lived in Missouri, but he eventually found his way to New Jersey, where he owned and published the Red Bank Register. At the time of his death on July 22, 1916, he was a book publisher in New York City.

Cook's deed of bravery and gallantry was finally recognized Sept. 19, 1890, when he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. The citation reads that "During an attack by the enemy, (Sgt. Cook) voluntarily left the brigade quartermaster, with whom he had been detailed as a clerk, rejoined his command, and, acting as a lieutenant, led the line . . . toward the charging enemy."

Phil Reyburn is a retired field representative for the Social Security Administration. He wrote "Clear the Track: A History of the Eighty-ninth Illinois Volunteer Infantry, The Railroad Regiment" and co-edited " ‘Jottings from Dixie:' The Civil War Dispatches of Sergeant Major Stephen F. Fleharty, U.S.A."

Sources:

Collins, William H. and Perry, Cicero, Past and Present of the City of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois. Chicago: the Clarke Publishing Co., 1905.

Beyer, W.F. and Keydel, O.F., Deeds of Valor: How America's Civil War Heroes Won the Congressional Medal of Honor. Stamford, Conn: Longmeadow Press, 1992.

Find A Grave Memorial, John Henry Cook (1840-1916).

Hicken, Victor Illinois in the Civil War. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1991.

Portrait and Biographical Record, Adams County, Illinois. Chicago: Chapman Bros., 1892.

The National Tribune (Washington, D.C.), July 16, 1896.

The Quincy Daily Herald, April 9, 1910.

The World (New York, N.Y.), March 13, 1898.

Wilcox, David F. editor, Quincy and Adams County, History of Representative Men, Vol. II. Chicago and New York: the Lewis Publishing Company, 1919.