Wood lent governor's office in Capitol to Lincoln

Lt. Gov. John Wood was perfectly satisfied to occupy the large upholstered mahogany armchair from which he served as speaker of the Illinois Senate from 1857 to 1860. It was the only job the state constitution prescribed for a lieutenant governor. Wood's friend Abraham Lincoln had nominated him for it. Four years later, Wood repaid the favor.

The job suited the 61-year-old Wood, and his Senate colleagues appreciated the way he performed it. As the 20th General Assembly adjourned Feb. 19, 1857, the senate's 25 members unanimously approved a resolution by Democratic Sen. William H. Underwood of St. Clair County: "The thanks of the Senate are hereby tendered to the Hon. John Wood the speaker for the able dignified and impartial manner in which he has discharged the duties of his office." Likewise, a correspondent for The Quincy Daily Whig wrote that he had "never observed a deliberate body dispatch business with such general harmony and good feeling. Gov. Wood metes out to all the same courtesy, and receives in return from all the same cordial feeling."

The statehouse in which Wood and other public officials worked was hardly accommodating. A most unseemly condition about the place were odors that frequently wafted up from the five copper pots -- or "cans" as they were called in that day -- in the basement privies three levels below. The relief rooms were rebuilt several times, each configuration as unsatisfactory as the last. Public use had only worsened their condition. So bad was it that the Legislature in 1857 felt compelled to pass a law that made any citizen's wanton abuse of the statehouse privies a crime punishable by fine of up to $100 or time in the Sangamon County Jail.

Statehouse occupants complained about other errors and oversights. In his design of the Greek Revival stone building, amateur architect John Francis Rague of Springfield failed to consider the growing population, additional representatives and public employees. Work spaces were cramped, and there were too few legislative committee rooms. Some contractors who took shortcuts were ordered to redo their work. Poorly placed wood stoves provided uneven heat throughout the building. At times, an empty state treasury delayed payments to contractors.

A decade after construction began, a frustrated Sen. Hugh Sutphin, who represented Adams and Pike counties, demanded an audit to determine how much longer construction would take. Three years later, an even more frustrated senator sought to move the capitol to Peoria. Construction continued up to the time the Legislature enacted a law to build a new state capitol in Springfield in January 1867.

Before the 1-year-old Republican Party nominated him for lieutenant governor in 1856, Wood had not expressed an interest in statewide office. He joined the first Republican ticket in Illinois only because his friend Lincoln and the party needed him to do so.

Calculating that he would appeal to the state's German voting bloc, Republicans had earlier nominated Francis Hoffman of DuPage County for lieutenant governor. When it was discovered that he did not meet the constitution's residency requirements, Lincoln, the party's nominating committee chairman, forwarded Wood's name. Wood's Quincy had significant populations of Germans and Irish. Lincoln believed that Wood would attract votes of both ethnic groups in Illinois to his party's ticket. That proved correct, and the William Bissell-John Wood ticket was elected over Democrats William A. Richardson of Quincy and Robert J. Hamilton of Chicago.

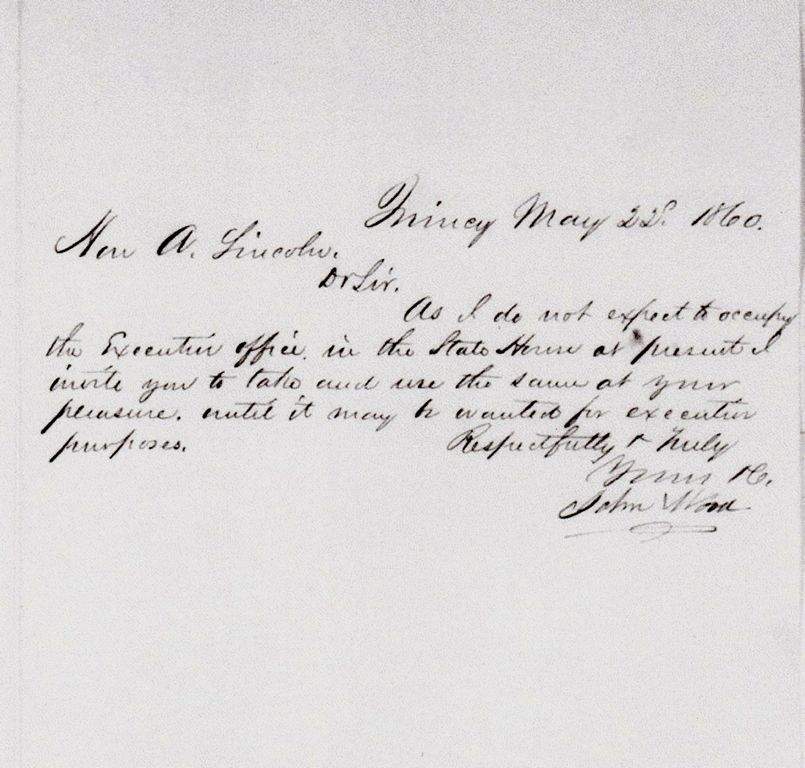

Although he became chief executive, Bissell never governed from the statehouse. An invalid, he remained bedridden in the new governor's mansion until he died there March 18, 1860. That elevated a reluctant Wood to governor, Illinois' 12th. Fortunately for Wood -- and for Lincoln, as it turned out, the Legislature had adjourned Feb. 24, 1860, and government agencies went into virtual hibernation. With more business at home in Quincy than at the capital, Wood, too, left Springfield. On May 22, 1860, Wood wrote from Quincy to his friend Lincoln, whom Republicans four days earlier nominated for the presidency, that he was welcome to use the unoccupied governor's office for his national campaign.

"Dr. Sir: As I do not expect to occupy the Executive office in the State House at present I invite you to take and use the same at your pleasure until it may be wanted for executive purposes. Respectfully and truly yours, etc., John Wood."

Lincoln was quick to take up Wood's offer. Within days, he moved into the governor's 15- by 25-foot reception room, furnished with a Brussels carpet, and the smaller executive office equipped with upholstered and plain wooden chairs, a table and desk. It was a showplace compared to Lincoln's law office, which was cheaply furnished and on the second floor of a building west of the statehouse.

Thousands of office-seekers, state delegations, well-wishers and newspapermen flooded through Wood's statehouse office while Lincoln occupied it. Party leaders and deal makers, who tried to influence Lincoln as he did his cabinet-making, came, too. On Nov. 23, the New York Herald reported that "Gov. Wood, of Illinois, is here after something."

Lincoln spent most of Election Day, Nov. 6, 1860, in the governor's office before leaving for the telegraph office on the square that evening to await results. Lincoln's partisans waited eagerly for the results in the House chamber across the hall from the governor's office.

The state's 11 electors arrived in Springfield on Dec. 5 and cast their votes for Lincoln. Gov. Wood signed the certifying documents later that day and placed them in two wax-sealed envelopes, whose outsides each elector signed to attest to their authenticity.

After his election to the presidency, Lincoln limited his hours in Wood's office from 10 a.m. to noon and 3:30 to 5:30 p.m. weekdays. On Dec. 29 and after seven months in the office, Lincoln had his secretaries John Nicolay and John Hay, both of Pike County, clear his papers and belongings and vacated the governor's office and reception room. Wood returned to them Jan. 7, 1861, to await the start of the 22nd General Assembly. A week later, Richard Yates was sworn in as governor. John Wood returned home to Quincy.

Reg Ankrom is a former executive director of the Historical Society and a local historian. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas, and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources:

Reg Ankrom, "Wood's German heritage helped him rise to governor," The Quincy Herald-Whig, July 12, 2015.

"Article V, Section 5," 1870 Illinois State Constitution, at https://archive.org/details/cu31924024668232 .

Charles A. Church, "History of the Republican Party in Illinois, 1854-1912." Rockford, Ill.: Wilson Brothers Co., 1912.

Harold Holzer, "Lincoln, President-Elect: Abraham Lincoln and the Great Secession Winter 1860-1861." New York: Simon and Schuster, 2008.

Robert Howard, "Illinois, The Prairie State." Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1972.

"Journal of the [1818 Constitutional] Convention," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. Springfield, Ill.: Phillips Brothers, printers, 1914.

Journal of the Senate of the General Assembly, State of Illinois, at their Regular Session Begun, and Held, in Springfield. Springfield: Lanphier & Walker, printers, 1857.

John Carroll Power, "History of the Early Settlers of Sangamon County." Springfield, Ill.: Edwin A. Wilson Co., 1876.

The Quincy Herald-Whig, Feb. 21, 1857.

Paul Simon, "Lincoln's Preparation for Greatness: The Illinois Legislative Years." Urbana: University of Illinois, 1971.

Sunderine and Wayne C. Temple, "Illinois' Fifth Capitol." Springfield, Ill.: Phillips Brothers printers, 1988.

John Wood to Abraham Lincoln, May 22, 1860. Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, MS920, WOO, File 1.