Emigrating from Germany could be long, arduous

The early German immigrants to Quincy and Adams County faced a long and arduous trip. Not only did the trip across the Atlantic present perils, but the usual trip up the Mississippi from New Orleans had its own dangers. In the 1830s, when these trips were made, Quincy was on the Western frontier. A letter from Joseph Mast Jr. (translated from the German), dated July 20, 1834, tells of his travel, most likely typical of the time.

Mast left France on April 1, 1834, along with 190 other people from the German state of Baden. Many were ill at the beginning of the trip. At least one fellow passenger was ill for more than 20 days, but all survived the trip to New Orleans. It took them 58 days to cross the Atlantic.

Mast was not fond of New Orleans. He wrote that slaves outnumbered white residents two to one. Cholera and yellow fever were both prevalent at the time. He describes how a cannon was fired in the city about 10 p.m. daily, the time of curfew.

The immigrants had trouble finding a boat to bring them to St. Louis. So they took one that traveled north to Louisville, Ky. They then traveled back down to the mouth of the Ohio, where they spent the night in the open before boarding another boat to St. Louis. On June 14, their boat from St. Louis to Quincy was rammed, and they thought it would sink. The boat didn't.

The ramming was a small hazard compared to yellow fever and cholera. Two boats left St. Louis after theirs, and eight people died on one and 28 on the other, all of cholera. Mast arrived in Quincy on June 16 without a place to live.

Joseph Mast Jr.'s uncle was Michael Mast, the first German resident of Quincy, arriving in 1829. He was a lifelong bachelor who owned five houses, but all of them were rented when Joseph arrived. Joseph and his companions found an old house by the river and fixed it up enough to live in it.

Anton Delabar, along with his wife, Barbara, and daughter Julienne, had arrived from Baden on March 29, 1833. A carpenter by trade, he never plied that occupation in Quincy. An enterprising man, he had several successful work projects while he lived in Quincy.

Delabar had written back to Baden telling residents to come to Quincy. He was a promoter of Quincy for the remainder of his life.

Joseph Mast Jr. did not see Quincy in the same light as Delabar. He thought Delabar exaggerated the opportunities in Quincy and was minimizing the risks. For instance, Delabar did not tell anyone that his own brother had died from cholera on his initial trip to Quincy and was laid to rest in the Mississippi.

Delabar did indeed find great success here. For a short time he ran a grocery store on Hampshire Street. Then he, along with another early pioneer, Henry Grimm, erected the first Quincy sawmill along the creek that powered it at Third and Delaware.

Delabar bought property from John Wood between Fourth and Fifth streets on the north side of Kentucky, and it was here that he erected Quincy's first brewery. The brewery burned at some point, and he then purchased property at Front and Spring streets. He later erected three large buildings on this site. This proved to be an astute property purchase for Delabar.

When the question of incorporating the city of Quincy was brought before its residents, Delabar was an election judge. When the votes were canvassed March 18, 1840, the vote was 228 in favor with 12 against. Subsequently, a city charter was adopted.

In 1845, Delabar organized the second German military company in Quincy, the Quincy Jaegers. The Jaegers continued until the Civil War in 1861, when they formed the nucleus of Company N, the German company of the 16th Illinois Infantry.

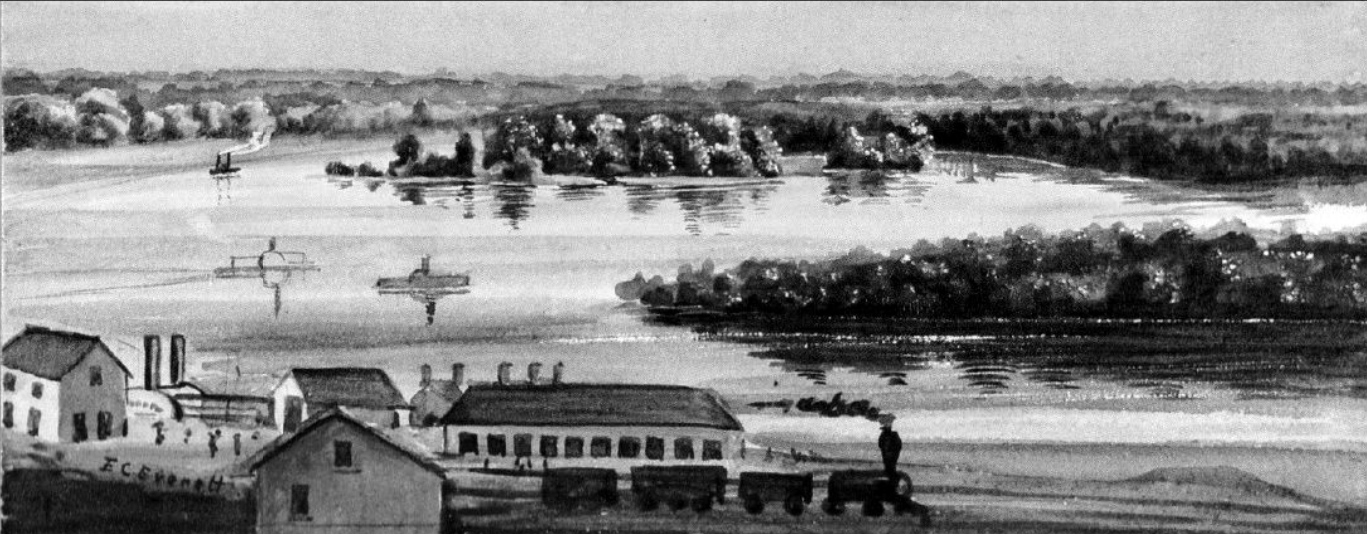

On Feb. 1, 1856, Delabar leased his saloon and part of his land on Front Street to the Northern Cross Railroad. This was a prime development location because it provided wonderful access to both the railroad and to the steamships that were coming up the Mississippi. He received the then princely sum of $600 a month for this lease. The office of the railroad and of its president, Nehemiah Bushnell, was kept in the saloon for the next few years. An Edward Everett watercolor painting, done in 1870, and on display at the History Museum, 332 Maine, shows the three Delabar buildings and the Northern Cross Railroad.

Anton and his son Charles then moved their brewery to the east side of 12th Street just north of Adams. The Ruff brewery was later built around this brewery by Casper Ruff.

Delabar and his family were devoted Catholics. The first church they attended in Quincy in 1835 was in a little building on Seventh Street between York and Kentucky. They also attended services in a poorly constructed frame building located at 11th and Broadway dating back to 1837. This was before the founding of Quincy's German Catholic Church, St. Boniface.

Barbara Linnemann Delabar, his wife, died in 1860, and is buried in Woodland Cemetery. Anton Delabar is not buried there. The place of his death is unclear. One story is that on a trip back to Baden, his ship sank at sea. Another story is that he died peacefully while in Schelingen, his hometown. The map of Woodland Cemetery says his burial plot is nee Anton.

Jack Freiburg is a sixth-generation resident of Quincy and a third-generation independent insurance agent. An avid outdoorsman, he is also a naturalist, and the proud father of three and grandfather of four.

Sources:

"Charles Delabar Former Quincyan." The Daily Herald, March 21, 1925.

"Death of Mrs. Kaeltz." The Daily Whig, July 19, 1895.

Joseph Mast Jr. to Baden (translated from the German), Author's Collection, Quincy, Ill.

Joseph Mast Jr. to his parents (translated from the German), July 20, 1824, Author's Collection, Quincy, Ill.

"Land Deed: Wood to Delabar," Adams County Recorder of Deeds, Nov. 25, 1834, Book C, 415.

"Obituary: Death of Anton Delabar, an old Quincy Citizen, in Baden." The Quincy Daily Herald, Aug. 30, 1879.

Wilcox, David, ed. Quincy and Adams County History and representative Men, Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Co., 1919.