Well-educated, well-traveled Quincy woman struggled late in life

Few young Midwestern girls in the early 1850s had the advantage of advanced education.

Almira Jane Williams, born in Quincy on Feb. 23, 1838, was one of the fortunate adolescent females able to pursue further education. Her parents, Archibald Williams and Nancy Kemp, married in Quincy in 1831. At 13, she had completed local schooling. Her father, Archibald Williams, considered one of Illinois' most important attorneys and a friend and colleague of Abraham Lincoln, enrolled her in the newly established Christian Female College (now Columbia College) in Columbia, Mo.

Almira Williams was registered as a member of the college's first class in 1851 and graduated July 4, 1854. A distant relative, John Augustus Williams, operated the college where study included philosophy, arithmetic, ancient history, grammar, ancient geography and composition.

Almira returned to Quincy under heartbreaking circumstances. Though she was one of nine children, only five lived to adulthood. Just months before Almira's graduation, her mother died in childbirth March 16, 1854. The Quincy Daily Whig reported that the funeral was held the next day in the family home. It is likely that Almira learned later of her mother's death. The new infant sister, Nancy, named after her mother, was likely a responsibility of Almira's on her return. The independence of her school years followed by personal tragedy was embedded at an early age and became thematic in her life.

In 1860, Almira was 22, living in the family home, and little Nancy was 6 years old. In November 1860, Almira married Dr. Charles Henry Morton, 12 years her senior. The couple never had children. Though Morton had previously practiced medicine and operated a drugstore, he changed his livelihood to the real estate business when he married.

A few months after the Civil War began, Morton was commissioned as a major in the 84th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment on Aug. 9, 1862. Slightly wounded at the Battle of Stone River in December 1862, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel on July 24, 1863. On Sept. 20, 1863, Morton was captured at the Battle of Chickamauga in Georgia and sent to the notoriously overcrowded and harsh Libby Prison in Richmond, Va., where "food was scarce, prisoners slept on the bare floor with no blankets and conditions were filthy." He was imprisoned for six months.

During Morton's enlistment, Almira was one of the founders of a local Civil War support group, the Needle Pickets. She served in one of the five local military hospitals and assisted in helping the families of soldiers. When Morton was reported "missing in action" Almira received a pass from Illinois Gov. Richard Yates to go anywhere within Union lines to search for her husband.

Her search was in vain. Morton eventually received a parole in March 1864, and was mustered out June 8, 1865. As reported in military records before being mustered out, Morton was not the same man after the imprisonment.

Almira, who was with her husband for the last six months of his service, commented in later depositions that during that time he was "morose, morbid and suspicious of his brother officers." She commented further that he became "suspicious of everybody and thought everybody, including myself, was conspiring against him." Morton carried a pistol day and night.

Though changed, life resumed in Quincy. Early in their marriage, Charles and Almira had planned to travel together to Europe. However, it was Almira who made the journey. With Quincyan Aldo Summer, and Kate Perry, a "spicy correspondent" of the Daily Gate City in Keokuk, Iowa, Almira sailed to Europe in October 1872.

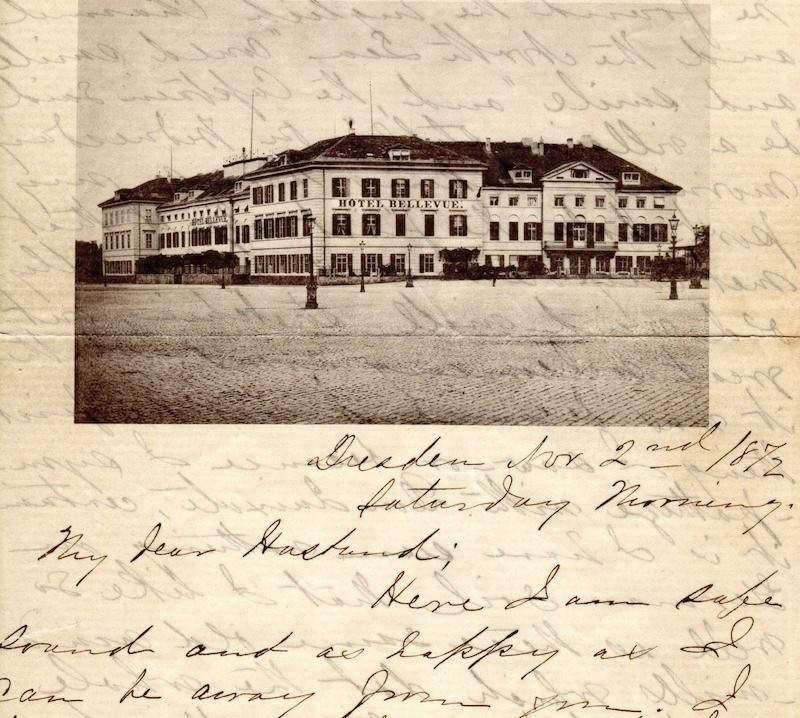

Summer and his family had traveled to Germany in 1870. The trio set out to spend a year traveling in Germany, England, France, Switzerland and Italy. With several letters of introduction and a general plan, they visited almost 100 cities. Almira especially loved Dresden, Germany, saying that six months in Dresden would not be a day too much.

Almira wrote dozens of descriptive letters to her husband relating the news of theater attendance, museums, art galleries and the public receptions with royalty such as one for Emperor William of Germany. Her observations were sprinkled with personal changes in perspective and particular enticements. News and notes of fellow Quincy travelers on somewhat simultaneous visits were also included.

"Myra," as she was known, recalled that her husband, Charles, had told her on their wedding day that they would go to Europe in five years. That was 12 years ago.

Morton's health and mental stability continued to deteriorate and after 20 years of marriage and three years of Civil War trials, he ended his life.

In the early morning hours of May 26, 1880, he committed suicide with a single gunshot wound to the right temple. The Quincy Daily News indicated that he was found in bed by his wife at their home on Sixth Street.

In 1880, as a highly educated widow in need of income, Almira worked for several months at the District Internal Revenue Service in Quincy. She left town in 1881, and for the next 20 years lived primarily in Washington, D.C., where she held a clerical position for the government.

In 1885, however, while living in Omaha, Neb., Almira filed an application for a Civil War widow's pension. She was denied and appealed three times. In 1890, the cause of Morton's war despondency and chronic physical ailments were finally viewed as "consistent with the history of similar cases of mental disease."

Morton suffered from what is today called post-traumatic stress disorder, often called "soldier's heart" in the aftermath of the Civil War.

A fragile Almira returned to Quincy a year before her death and lived with family at Sixth and Cedar streets. Several years earlier she had been severely injured when a bicycle rider ran into her. A progressive paralysis resulted. She died Aug. 26, 1904, at age 66 and was buried next to her husband in Woodland Cemetery in Quincy.

Iris Nelson is retired from her position as reference librarian and archivist at the Quincy Public Library. She serves on boards for civic and historical organizations and has written articles for historical journals.

Sources:

"Death of Mrs. Almira Morton," Quincy Daily Whig, Aug. 27, 1904.

"Died." Quincy Daily Whig, March 17, 1854.

Hattenhauer, John. Col. Charles H. Morton, 1826-1880, 84th Illinois Infantry, research file. Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

Letters (excerpts) from Almira Morton to her husband, C.H. Morton, on her trip to Europe, October 1872 to August 1873. 41 letters. Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.