Salvation Army came to town and wasn't always welcomed

A 19-year-old pawnbroker's apprentice named William Booth, who had been working in this trade since the age of 13 after his father died, left home in Nottingham, England, in 1849 and moved to London. There he continued working in a pawn shop six days a week and preaching on the seventh. Three years later, he was a full-time Wesleyan Methodist preacher and had fallen in love and married Catherine Mumford, a devout Congregationalist ministering to London's sick.

Catherine was herself sickly as a child and from a young age had abstained from using sugar out of compassion for the "colored races of the earth." The couple began raising a family and a circuit ministry especially devoted to England's destitute and displaced.

Their work continued until 1865, when, weary of the theological debates raging at a time when people desperately needed help, the Booths broke away from the established church and formed the Christian Revival Society. They had found their life's calling. One day in 1878 as William was dictating a letter to his secretary, he said, "We are a volunteer army." His son Bramwell overheard him and exclaimed, "I'm no volunteer, I'm a regular!" William crossed out the word "volunteer" and replaced it with "salvation." Thus began the Salvation Army.

Although widely thought of as a social service organization, the Salvation Army is a Christian church whose mission in dispersing the three S's -- soup, soap and salvation -- is to "preach the gospel of Jesus Christ and to meet human needs in His name without discrimination."

The church soon spread throughout England, and in 1880, with Eliza Shirley and her parents' evangelism, crossed the Atlantic and entered the United States. In 1892, the Salvation Army came to Quincy.

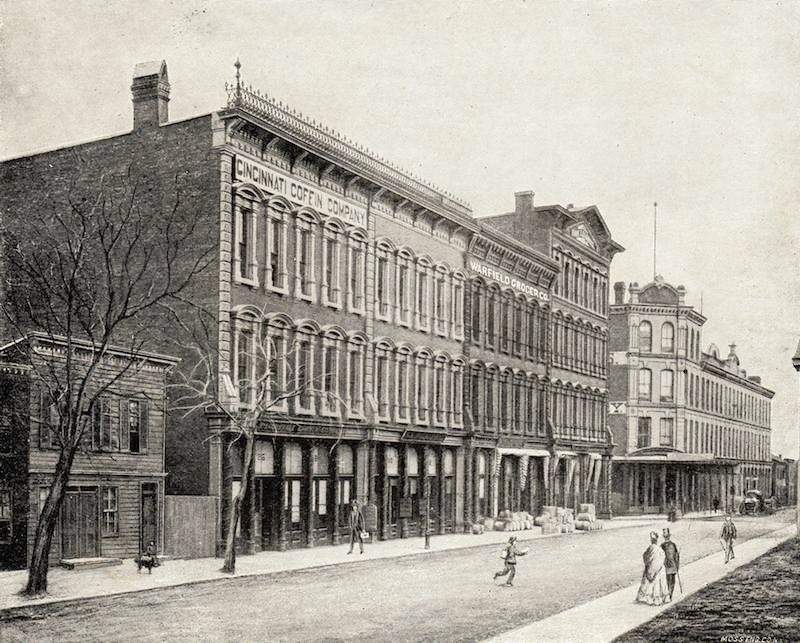

As with most communities encountering the early Salvation Army, Quincy did not welcome it with open arms. Soon after its arrival, an editorial in The Quincy Daily Journal stated, "There exists considerable prejudice against the Salvation Army. They are not ‘high church' in their methods." The editorial continues, though, "There is material in this city for them to work on. Our gutters are not free from drunkards. Quincy has her full share of brothels. Quincy has an Adams row, a Merssman row, an under-the-hill population." Prostitution, gambling, and alcoholism blighted these neighborhoods.

Indeed, the methods used by the local Salvation Army radically veered from conventional ecclesiastical ways: after vowing abstention from alcohol, tobacco and gambling, followers regularly marched through the streets banging drums and singing, evangelizing to people in saloons and in parks, and held noisy open-air meetings nearly every night of the week.

A year after its arrival, meetings were drawing large crowds and also widespread anger among citizens, who mostly saw them as "strange people with their uniforms and bonnets." Stating that streets belonged to the public, store owners railed that the loud music and unrestrained evangelical fervor were driving away customers and incensing both humans and horses. In May of 1897, members defied police by marching along the streets, and several were arrested.

A schism in the church in 1896 over how autonomous the U.S. branch should be created a splinter group called Volunteers of America, headed by William Booth's son Ballington and his wife, Maud, and in 1901 this faction located in Quincy. The Daily-Whig stated that this group's work was almost identical to the Salvation Army and asked in a headline "Can Quincy Support Both Organizations?" The two rivals coexisted for the next 40 years with both promising no overlapping of solicitations.

While hostile store owners and churches would continue to plague the Quincy Salvation Army Corps for many years, forcing it to move its headquarters from its original location in a second-floor room on Third Street between Maine and Hampshire 15 times in its first 16 years, its "Save the Drunkards" meetings, jail ministry, employment bureau, annual Christmas dinner and staff "slum nurse" began revealing its noble work.

Miss Sadie Stewart, the slum nurse, assigned to practically aid those in the most squalid neighborhoods, advised families on home economics and child care: repairing clothes, baking bread and spreading household income to meet needs. Many families in Quincy, she observed, survived on $12 to $18 a week and much unemployment existed. Some people's poverty came from "shiftlessness," but most could be helped, and the city, she said, was a "fruitful vineyard in which to labor."

The early corps also began espousing enlightened ideas that set a course for other churches. Catherine Booth regularly preached alongside her husband at a time when women were almost entirely excluded from the pulpit, and the corps has from its beginning ordained women. Capt. Lizzie Boyler of the St. Louis Salvation Army established the Quincy Corps and, although not widely recognized by other denominations, was likely the first female minister in the city.

At the Second International Salvation Army Congress in 1894, William Booth took five black people with the American delegation to show his church's universal evangelism among all races and ethnic groups. The Quincy Salvation Army was the first local church to largely integrate its congregation at a time of great racial prejudice.

The turning point, though, for the corps' image in Quincy and the United States came with World War I, as members volunteered to aid troops on the front and raise money for the war effort. In 1917 the Quincy Salvation Army netted $10,000, and both public and police sentiment began to change. Chief of Police George Koch and Mayor William K. Abbott praised its work. Only one year earlier (before U.S. involvement in the war) the president of the Quincy Welfare Federation had announced that the Salvation Army's mailing of solicitations to businessmen violated its fundraising agreement.

The Salvation Army finally purchased property on Fifth and Broadway to construct a permanent headquarters, and in 1920 formed an advisory board to oversee operations. In 1924 it began publishing a local magazine, Our Advisor, but by now the Salvation Army was dovetailing into the mainstream of life here while still remaining an evangelical Christian church with the same original mission and largely the same methods.

Joseph Newkirk is a local writer and photographer whose work has been widely published as a contributor to literary magazines, as a correspondent for Catholic Times, and for the past 23 years as a writer for the Library of Congress' Veterans History Project. He has been active in the Quincy Salvation Army for more than 20 years.

Sources

"Can Quincy Support Both Groups?" Quincy Daily Whig, May 8, 1901, page 8.

"Christmas Dinner For Poor Children," Quincy Daily Whig, Dec. 7, 1896, page 3.

"Fraudulent Solicitors," Quincy Daily Whig, March 26, 1898, page 8.

Genosky, Rev. Landry. "People's History of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois: A Sesquicentennial History." Quincy, Ill.: Jost & Kiefer Printing Co., 1974, page 99.

Hattersley, Roy. "Blood and Fire: William and Catherine Booth and Their Salvation Army." New York: Doubleday, 1999.

"Located," The Quincy Daily Journal, Dec. 1,1892, page 3.

McKinley, Edward H. "The History of the Salvation Army in the United States of America 1880-1980." San Francisco: Harper & Row Pub., 1980.

"Noisy Drums Cause Horse to Run Away" Quincy Daily Whig, July 16, 1904, page 8.

"Quincy, Too, Has Slums, Nurse Says," Quincy Daily Herald, June 28, 1925, page 9.

"The Salvation Army," Quincy Daily Whig, June 7, 1893, page 3.

"The Salvation Army Board to Meet Today," Quincy Daily Whig. June 30, 1920, page 5.

"The Salvation Army Defies the Police," The Quincy Daily Whig, May 16, 1897, page 1.

"Salvation Army Employment Bureau Adds to Service," Quincy Daily Herald, Oct. 7, 1924, page 3.

"Salvation Army Has Magazine," Quincy Daily Journal, Oct. 15, 1924, page 8.

"Salvation Army War Fund Drive," Quincy Daily Herald, Sept. 11, 1918, page 9.

"Salvation Army Work Here: The Save Drunkards Meeting," Quincy Daily Journal, Nov. 9, 1905, page 8.

"Salvation Army Work is Praised," Quincy Daily Whig, Dec. 26, 1916, page 3.

"Says Salvation Army Violated its Agreement," Quincy Daily Whig, Dec. 14, 1915, page 2.

"Slum Nurse of Salvation Army Does Good Work," Quincy Daily Herald, June 10, 1925, page 11.

"Street Belongs to the Public," Quincy Daily Whig, Oct. 22, 1901, page 5.

Winston, Diane. "Red-Hot and Righteous: The Urban Religion of the Salvation Army." Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999.