Lost 19th century artworks of Edward Everett return to Quincy

Eager for business when he arrived in Quincy from London with his family in 1840, Edward Everett, 22, did not consider himself an artist. In city directories and military records, he referred to himself as a mechanic and engineer. Yet his mastery of brush and pen led to his appointment to renovate the war-battered Alamo in Texas. And in 1985, curators of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas, called him one of the finest watercolorists of his time.

Eleven of Everett's paintings and drawings -- landscapes of the Quincy area he did between 1840 and 1857 -- disappeared from the city in the early 20th century. Recently discovered, however, they were acquired by the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

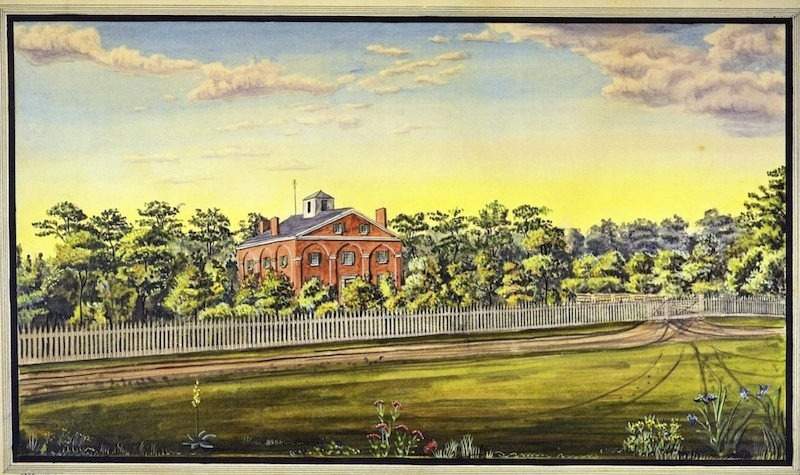

Everett's use of watercolors for his Quincy subjects ranges from faint pastels to rich colors in paintings of farms and mounds and steamboat commerce on the Mississippi River. For his river work, Everett perched himself on the bluff above the bay at Oak Street to survey the traffic and stores at the Quincy landing. Although his family's large brick Italianate home at 801 N. 12th was razed decades ago, one of the Everett watercolors recalls the homeplace and the six acres on which it was situated. Everett's father, Charles, built the brick house on the southwest corner of Elm and 12th in 1843.

Other pieces from the historical society's archives, including a map of the city Everett drew in 1857, will be included in the exhibit.

Born on March 31, 1818, in London, Everett was named for his father's cousin. The elder Edward, a minister, baptized the boy while visiting the family that year. Acclaim showered the older Edward, a 19th century educator, politician and orator. Civil War historians know the elder Edward Everett for a two-hour speech that preceded Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, delivered in less than three minutes. The speeches dedicated the federal cemetery at Gettysburg, Pa., during the Civil War.

Everett's parents were born in Boston. His father Charles was a merchant there until 1815, when he moved his family and a growing international trading business to London in 1816. The younger Everett apprenticed in the business. In 1834, his father sent him to Boston to learn the import business in America. The boy returned to London and school in 1836, worked once again for his father, then accompanied the family to Quincy in 1840. Everett branched out from the family's business, a general store on the east side of the public square. He opened his machinist/engineering business on Maine Street just west of the square. The family's earnings and social acumen were strong enough to build the home on North 12th, which Everett family friend Cora Benneson described as "a roomy mansion which became a centre of hospitality."

The extent of Everett's education in art is not known, but art historians have likened his work to the 19th century Hudson River School of artists. In romanticized portraits and landscapes, their work reflected an expansionist young America, which at the time sought the annexation of Texas, Canada and Cuba. Quincy Congressman Stephen A. Douglas led the "Young America" wing of the Democratic Party.

The first artwork to suggest Everett's style was a drawing of the Mormon Temple in Nauvoo in April 1846. He had seen the new structure a year earlier as a member of the Quincy Rifles, a local volunteer militia. Gov. Thomas Ford had ordered the local volunteers to help restore peace to the Nauvoo area during the Mormon War of 1845. Everett's temple sketches and drawings foreshadowed his most-acclaimed works, done in 1847 during the Mexican War.

Everett was with the Quincy Riflemen when ordered by Ford on June 16, 1846, to join the First Regiment of the Illinois Volunteer Infantry for service in the 2-month-old Mexican War. Everett questioned the war "in which there was so little to be gained in either honor or profit." Fortuitously, Col. John J. Hardin of Jacksonville, commander of the First Illinois, assigned Everett to collect information about the history and customs of places "on the line of march, and of making drawings of buildings and objects of interest, particularly ... of San Antonio."

In September 1846 Everett made pen-and-ink drawings of the Alamo, which had been battered during Texan-Mexican battles there 10 years earlier, and two other mission churches. Fortune cut short any further chance of armed duty on Sept. 11, 1846. While on patrol in San Antonio, he was shot in the right knee by a rowdy patron of a gambling house. The doctor treating the wound judged Everett "wholly disabled from obtaining his subsistence by physical labor."

A month later, Capt. James H. Ralston of Quincy, recently appointed assistant quartermaster, arrived in San Antonio. Learning of Everett's condition, he called on his Quincy acquaintance and asked him to serve as chief clerk in the Quartermaster Department in San Antonio. He also relied on Everett to help supervise the renovation of the Alamo, whose interior and exterior Everett had recently drawn. When reconstruction was finished, the Alamo served the Quartermaster Department as a depot for supplies and materials storage, offices and workshops.

Everett returned to Quincy and the family home in 1850. On Oct. 7, 1857, he married Mary A. Billings, who at 19 was 20 years younger than he. They had no children.

Quincyan John Wood was appointed Illinois quartermaster general at the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 and was perplexed by the level of detail required. With no accounting system in place and himself unsystematic, Wood asked Everett to be assistant quartermaster. He did.

After the war, Edward and Mary Everett lived in New York until 1893, when they moved to Roxbury, Mass., to be near her sister. There Everett died on July 24, 1903.

Reg Ankrom is a former executive director of the Historical Society and a local historian. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas, and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources:

Richard Eighme Ahlborn, "The San Antonio Missions: Edward Everett and the American Occupation, 1847." Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum of American Art, 1985.

Cora Agnes Benneson, "The Work of Edward Everett of Quincy in the Quartermaster's Department in Illinois during the First Year of the Civil War." Transactions of the Illinois State Historical Society for the Year 1909. Springfield: Illinois State Historical Society, 1910.

Bill Bradshaw, "Everett House is Doomed; Once on the Underground Railroad," Quincy Herald-Whig. Dec. 21, 1969.

"Edward Everett, 1794-1865." Inventory, Harvard University Library, at oasis.lib.harvard.edu/oasis/deliver/~hua11005

"On the March to the Mexican War." Transactions of the Illinois State Historical Society for the Year 1905. Springfield: Illinois State Historical Society, 1906.

"Edward Everett." The Handbook of Texas. Online at tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fev15

Edward Franklin Everett, Descendants of Richard Everett of Dedham, Mass. Boston: Privately printed, 1902.

"First Lithographs of the Alamo from Eyewitness Drawings, Auction 23," at dsloan.com/Auctions/A23/item-alamo-report-1850.html

Patricia A. Junker, An American Collection: Works from the Amon Carter Museum. New York: Hudson Hills Press, 2001.

Bob Keith, "Edward Everett was Quincy's jack-of-all trades." Herald-Whig, Aug. 7, 2016.