Epidemics, Quarantines, and Vaccines

Epidemics have been around for centuries. The earliest known epidemics in America were smallpox and yellow fever in the 18th century, followed by several cholera outbreaks in the 19th century. Even before Illinois became a state in 1818, it had suffered epidemics of influenza, smallpox, and scarlet fever. Quincy’s first recorded epidemic was cholera in 1833. Civic minded citizens formed a temporary board of health, which met every day at the courthouse. They divided the city into wards and raised money to feed the sick and bury the dead. Quincy lost 6% of its population. With little understanding of contagion and without curative medicines, the only method to stop the spread of disease was quarantine. For Illinois residents, the first documented quarantine was in 1799. Southern Illinois residents were prohibited from crossing the Mississippi River to St. Louis due to a smallpox outbreak.

In Quincy throughout the 19th century public health work and a functioning board of health was sporadic. One was appointed in Quincy in 1865 and reorganized in 1869, due to the need for a proper morgue and a death certificate stating cause of death. The board’s concerns for clean water, safe food handling, and proper sewers were a start toward the goal of preventing disease and promoting public health for the community.

Dr. Harry Otis Collins who practiced in Quincy after graduation from Keokuk Medical College in 1897, was an early proponent of public health. He became the city physician in 1912. This physician was responsible for the health of the community, particularly the indigent citizens or visitors to the city. Dr. Collins became the health officer for the city department of health in 1931 and was also active in the later county-wide campaign for a combined health department.

Quincy was the first city in Illinois to take advantage of a law passed by the legislature in 1917 which allowed for the formation of a public health district supported by local taxes. But it was not until 1922 that Quincy had an official health department with offices in the Majestic Building. The department opened in May and held an open house for the public. The Quincy Daily Herald reported on May 10, “This city has one of the most efficiently organized and conducted health departments in Illinois.” The health department was divided into divisions, communicable disease, clinical laboratory, sanitation, quarantine, and registration of births and deaths. Later in 1922, a Quincy Daily Herald article headline read, “Epidemic in Riverside is Averted: Health Department Acts Quickly When Scarlet Fever is Found,”. It referred to school children in Riverside Township where active cases were quarantined, and the rest of the children monitored for symptoms.

Legislation was passed in 1945 which enabled Illinois counties to levy taxes to establish a county-wide board of health. As the city of Quincy before it, Adams County was first to pass a referendum in 1946 to establish such a board of health. Dr. Collins was director. In 1947 the city and county health departments merged to become the Adams County Health Department. In addition to an appointed board, the department consisted of a professional staff which carried out various duties, among which was to promote and protect public health, control communicable diseases, and manage a sanitation program. After 16 years, the department moved to a new building designed specifically for it. An entire section of the September 22, 1963, edition of the Quincy Herald Whig was devoted to the Adams County Health Department’s history, services, and new building.

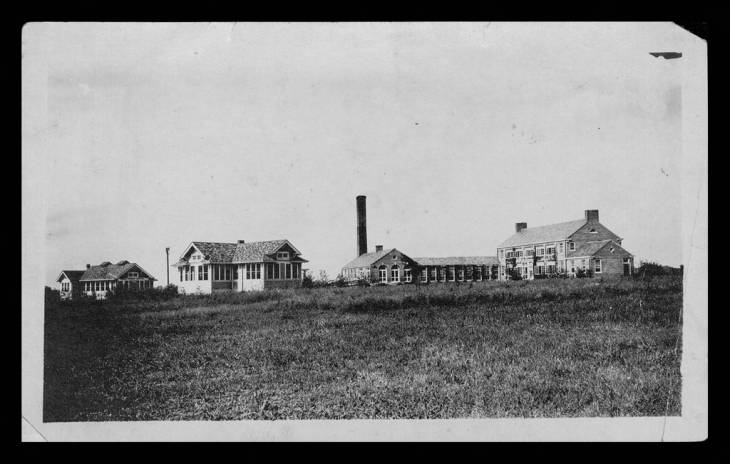

With the health department monitoring communicable diseases, home quarantines were used for diseases such as diphtheria, measles, scarlet fever, and influenza. Large signs were placed on houses and businesses warning others to stay away. The leading cause of death in the early part of the 20th century, tuberculosis, required isolation. The Glackin Act passed in 1915 allowed counties to tax their citizens to build sanatoriums. Adams County did take advantage of that tax and built Hillcrest sanatorium, which opened in 1920 and treated active tuberculosis cases until it closed in 1968.

Vaccine history is not as old as recorded epidemics. The first successful vaccine was used against smallpox. Vaccinations against smallpox were known in the 18th century but not widely used. Some sources claim the Chinese were using vaccinations in the 16th century. In the United States, each state was responsible for public health and vaccinations. In Illinois, the Department of Public Health organized in 1870, began requiring smallpox vaccination in 1881 for school admission. In Quincy in 1871, Dr. A. R. Platt, city physician vaccinated 604 people against smallpox. The city board of health had free vaccinations. Today, smallpox is the only communicable disease that is considered globally eradicated thanks to the vaccine.

By 1963, vaccines were also available for diphtheria; pertussis; also known as whooping cough; tetanus; and polio but not for measles or chickenpox, which were the largest number of communicable diseases in Adams County that year. One of the biggest vaccination success stories against disease was polio.

The first recorded outbreak in Illinois was in 1916. The disease was highly contagious with the most severe cases requiring an iron lung machine enabling patients to breathe. On March 26, 1953, Dr. Jonas Salk announced that he had successfully tested a polio vaccine. After even larger trials, the vaccine was available in 1955. At that time, the state of Illinois authorized an emergency appropriation of $1 million for free vaccine distribution. The Salk vaccine was an injection while the Sabin vaccine, developed by Albert Sabin was given orally on a sugar cube. The Sabin vaccine, although developed around the same time as Salk’s vaccine, was not licensed for distribution in the United States until 1961. As polio affected adults as well as children, the Adams County Health Department urged everyone over two months old to take the vaccine. They set up clinics in October 1963 as did most of the surrounding counties and planned to vaccinate 50,000 people.

As we recently learned, epidemics and quarantines are with us today. So are vaccines.

Sources

“86 Years Ago in IDPH History.” Illinois Department of Public Health. http://www.idph.state.il.us/webhistory19.htm

“A Century of Progress (1850-1950). Quincy, IL: The Royal Printing Company, 1950.

Dittmer, Arlis. “Ralston was Key in Fighting Cholera Epidemics,” Quincy Herald Whig, March 8, 2015.

“Epidemic in Riverside is Averted.” Quincy Daily Herald , September 24, 1922, 14.

Genosky, Rev. Landry, ed. People’s History of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois; a Sesquicentennial History. Quincy, IL: Jost and Kiefer, 1970.

“Health Services Born in Plague During First Decade of County’s Life.” Quincy Herald Whig , September 22, 1963.

The History of Vaccines: An Educational Resource By The College of Physicians of Philadelphia. https://www.historyofvaccines.org

Hopf, Matt, “Was a Tuberculosis Sanatorium Ever Built in Adams County?” Quincy Herald Whig, February 25, 2019.

“Immunization Health Bulwark.” Quincy Herald Whig , September 22, 1963, D4.

“Mass First Oral Polio Clinic is Oct. 13.” Quincy Herald Whig , September 8, 1963, A22.

“Monday Open House Day at Department of Health Offices.” Quincy Daily Herald , May 10, 1922, 2.

“New Home is Highlight of Year.” Quincy Herald Whig, September 22, 1963, D1.

“Public Health in Illinois: A Timeline of the Illinois Department of Public Health.” Illinois Department of Public Health. http://www.idph.state.il.us/webhistory19.htm

Rawlings, I.D., M.D. The rise and fall of disease in Illinois, Volume II. Springfield, IL: The State Department of Public Health, 1927.

Salk vs. Sabin - The Polio Vaccine (weebly.com)

“War on Polio Reaches Quincy.” Quincy Daily Whig , February 2, 1917, 3.