Europeans began immigrating to area in 1840s, '50s

Most of the settlers of Quincy and Adams County, who arrived in the 1830s, had lived in another state before heading west -- often Ohio, New York, Connecticut or Kentucky. They had varying reasons for coming here. Land grants, called bounties, for 160 acres in what was to become Adams County were granted to veterans of the War of 1812; religious fervor of the Second Great Awakening motivated the establishment of new communities of people who shared a faith; and the next generations of young Americans after the American Revolution were ready to start new lives and new adventures in the newly available land west of the Appalachians.

The first settlers of Payson came from Connecticut to form a Congregational community, and the settlers of Liberty came north from Kentucky to escape slavery and establish a community around their Brethren church. Then within a short time, a vast wave of immigrants from western Europe came to the county.

Political, agricultural and economic crises in the 1840s and '50s became the impetuses for European settlers to come to America, and many came to Illinois. In 1850, more than 80 percent of the foreign-born men living in the state had been born in Germany, Ireland or England. Many families came directly from their homelands to Adams County, instead of spending generations in the East, like the earlier settlers. The community of Golden was established by more than 200 families from Frieslandia, a region on the North Sea that later became part of Germany. Families from England built a settlement in Beverly Township.

Being a citizen, and/or speaking English, had never been required for voting in Illinois. "(T)he Illinois Supreme Court explained: ‘It is well understood that it was the policy of the congress of the United States, at the formation of the ordinance of 1787, to invite emigration into the northwestern territory. And hence, as one strong inducement for emigration the right of suffrage was extended to aliens in those territories, as they should be successfully formed out of the northwestern territory proper.' " (Hayduk, 2016). The first State Constitution, in 1818, continued the practice.

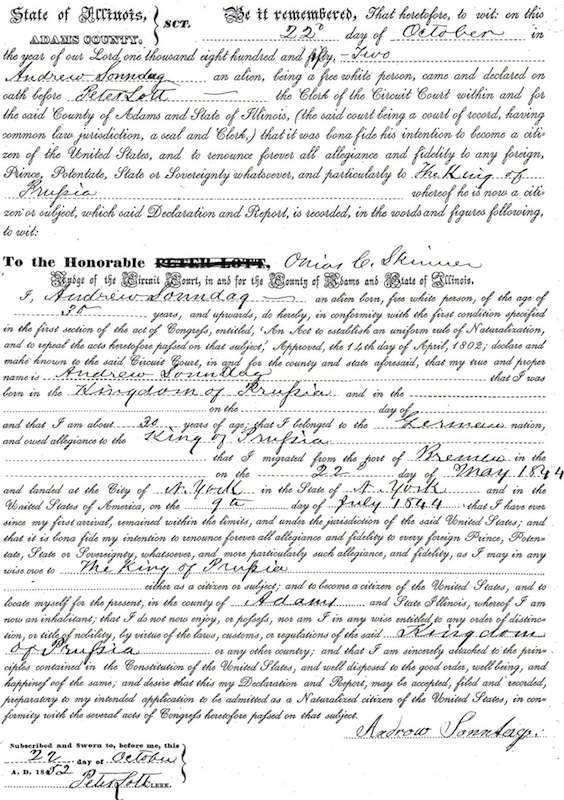

An immigrant who becomes a citizen is said to be "naturalized." Naturalization begins with filing a Declaration of Intention after two years of residency, then three years later, an application for citizenship. The Constitution charges Congress with creating the process for it, and the one in effect in the early years of Quincy was passed April 14, 1802. The rules applied only to men, whose family members gained citizenship when they did.

In 2002, the Great River Genealogical Society published a collection of the Declaration of Intention documents that had been signed by various Adams County clerks from 1840 to 1852 under the title Alien Report (Declaration of Intention) 1840-1852 Adams County, Illinois. The first seven entries in the book reveal some surprising information.

The statement the applicant had to sign began: "Be it remembered, That heretofore, to wit: on this ___ day of ___ in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and ___an alien, being a free white person, came and declared on oath… ." They then declared their birth date and place, nation and sovereign to whom they were renouncing allegiance, and their ports and dates of departure and arrival.

The first four men who completed a Declaration of Intent in the spring of 1840 were all 39 to 45, and three of them were from Great Britain, but they seemed to have little else in common. The fourth, Michael Toway, was prepared to renounce his citizenship in the "Republic of Switzerland," and declared that he had sailed from Havre de Grace in France to New Orleans.

Thomas Milner, 46, was a citizen of the "English nation," owed allegiance to the "King of England," and had sailed from Liverpool to New York City.

Cornelius Sulivan filed a week after Milner, on April 14. He stated that he was from the "County of Cork in Ireland," was renouncing his citizenship in the "Kingdom of Great Britain," and his allegiance to the "King of Great Britain." The handwritten script in the blanks filled in on his document indicates that he sailed from the Irish port of Cork to Lubeck (Lubec), Maine.

Lubec is a small town known as the community farthest east in the contiguous United States, but it claims five lighthouses in the area and only a pier for the island ferry -- it is not a port. How did Milner land there?

On the same day, John Sherren, 39, stated that he had been born in "Rye in the County of Donegal in Ireland" (which required writing between the lines, because the blank for place of birth wasn't long enough). He also owed allegiance to the king of Great Britain, but had sailed from Londonderry, Ireland, to "Quebec in Canada and immediately proceeded my journey from France to Troy in the State of New York," an explanation that also required writing between the lines because of insufficient space in the blanks. Troy is a city in western New York on the Erie Canal, which settlers often used to reach the Great Lakes and points west.

Entries from the last year in the collection, 1852, were quite different from the ones in 1840. Three men filed their Declaration of Intent on Oct. 22, 1852. Andrew Sonndag, 30, was from the "German nation," owed allegiance to the "King of Prussia" and had sailed from Bremen to New York City. John Kull of the "Swiss nation," sailed from Le Havre to New Orleans. Joseph Pokenbower considered himself a citizen of the "German nation," but owed his allegiance to the "King of Bavaria." He had also sailed from Bremen, but landed in New Orleans.

Clearly, the flood of immigration in the 1840s and 1850 represented people from varying backgrounds who were willing to access a range of means and places in order to come to America, settle in Adams County and become American citizens.

Linda Riggs Mayfield is a researcher, writer and online consultant for doctoral scholars and authors. She retired from the associate faculty of Blessing-Rieman College of Nursing, and serves on the board of the Historical Society.

Sources:

1850 Census Adams County, IL (1983). Volume I. Great River Genealogical Society.

Alien Report (Declaration of Intention) 1840-1852 Adams County, Ill. (2002) Great River Genealogical Society c/o Quincy Public Library, Quincy, Ill.

Census Online. census-online.com/links/IL/Adams/

Franken, LaVerne A. (1999). History of the "New East Friesland" Colony at Golden, Illinois. http://adams.illinoisgenweb.org/History/golden_history.html

Hayduk, Ron (2016) (website). The History of Immigrant Voting Rights in Illinois. The Immigrant Voting Project and New York University Law Students for Human Rights.

ronhayduk.com/immigrant-voting/around-the-us /state–histories /illinois/

Lubec, Maine: Small Town. Great Outdoors. (website}. visitlubecmaine.com/

Meyer, Douglas K. (1998). Foreign Immigrants Illinois 1850. lib.niu.edu/1998/iht519815.html.