Lincoln knew enough about Know Nothings to keep distance

Both major political parties in mid-19th century America sought the sizable and growing vote of immigrants. In Illinois, Stephen A. Douglas and Abraham Lincoln had struggled against each other for nearly two decades to win the "foreign vote," Douglas for the Democrats and Lincoln for his Whig Party and after 1856, for the Republican Party.

Lincoln and Douglas were their parties' presidential candidates in 1860. By that time, Irish immigrants had aligned with the Democrats and Germans, who had first favored Democrats, now were aligned with the Republicans.

When Quincy lawyer Abraham Jonas wrote Lincoln on July 20, 1860, that local Democrats planned to publish charges that Lincoln had visited a Know Nothing lodge when he was last in town, an alarm sounded.

Know Nothings was the nickname given members of the American Party -- occasionally also called the Nativist Party, whose members refused to admit they were part of a divisive, anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic party. Meetings were conducted in secret, and members were pledged to say they knew nothing about what went on in those meetings.

Loosely organized in the early 1840s, Know Nothings solidified by 1854 as the population of foreign arrivals swelled. The party achieved its greatest influence in 1856 when former Whig President Millard Fillmore won nearly 22 percent of the popular vote and eight electoral votes as the American Party's presidential candidate. While the Know Nothings' political strength had declined by 1860 -- its members folded mainly into the Republican Party -- the Know Nothings were still influential in some northern states, including Illinois. That was the reason for Jonas' letter to Lincoln.

"... Isaac N. Morris is engaged in obtaining affidavits and certificates of certain Irish men that they saw you in Quincy come out of a Know-Nothing lodge," Jonas warned Lincoln. "The intention is to send the affidavits to Washington for publication."

Morris was a Democratic congressman and Quincy resident. His object, Jonas warned Lincoln "is to work on the Germans (vote) -- and Morris can get men to swear to anything." By Lincoln's calculations, he would need both the Know Nothing and the foreign vote. Linking him to the Know Nothings could jeopardize his appeal to the latter.

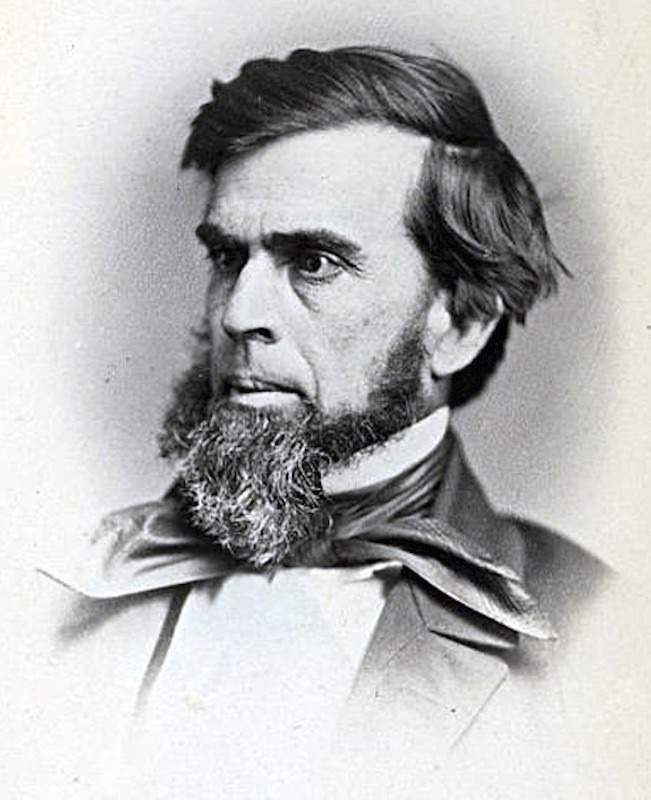

Getting the German vote was the reason Lincoln in 1856 nominated five-time Quincy mayor and former state senator John Wood for lieutenant governor. Wood was a favorite of German voters and elected on the first statewide Republican ticket. He beat Democrat Richard Jones Hamilton, running mate of gubernatorial candidate William Alexander Richardson of Quincy, and Know-Nothing candidate Parmenus Bond.

Wood knew the insidious character of nativism in his city. Quincyans felt a growing threat in the tide of immigrants. In his 2010 study, "Quincy Illinois, Immigrants from Munsterland Westphalia Germany," Michael K. Brinkman noted that nativism was strengthening in the community through the 1840s. Brinkman's analysis of census data showed that by the end of the decade nearly 38 percent of Quincy residents were foreign born, most of them Germans. The tide of poor immigrants induced fears of amalgamation, the loss of Anglo Saxon culture and language, lawlessness and crime, and lower wages for workers.

Quincy Know Nothings in March 1847 fielded a full slate of candidates for local offices. All Know Nothing candidates lost. But fear of foreign influences continued to prey on minds of many Quincyans, and nativism grew.

The Quincy Whig published a letter from "A Son of America," who complained that "corruptions abroad have swelled the hordes of fugitives to our country, until the American is in danger of becoming a stranger in his own native land." The writer suggested that selfish interests "have shaken the foundation of our freedom, and we, the proper children of the land, combine for their protection."

Judge Peter Lott of Quincy said the "foreign vote" was the strength of the Democratic Party in Adams County. After local elections in 1848, Lott's examination of the poll books showed that "of the 1,050 votes cast it would be found that less than one-fourth of those who had voted the democratic ticket were native born, and it had been nearly so in proportion for several years past."

Ultimately challenged for the foreign vote, Quincy's Democratic Party, press and politicians prevaricated to keep it. In 1852, Congressman Richardson of Quincy erroneously claimed that Whig presidential nominee General Winfield Scott wanted immigrants to serve two years in the Army before they could be naturalized. When Whigs denied Richardson's claim, the Democratic-oriented Quincy Herald created a new one. It claimed that Whig candidates for the state legislature favored a law to prohibit liquor in Illinois. That did not sit well with the city's German and Irish populations, whose frequent drinking of beer and alcoholic beverages was normal in their cultures. Democrats, the newspaper crowed, opposed the "Maine Liquor Law," so named for the state in which the prohibition had been recently imposed.

Answering Jonas, Lincoln said he once before had been accused of being in a Quincy Know Nothing lodge. In 1854, Lincoln spoke in Quincy in behalf of Archibald Williams, who was challenging Richardson for his congressional seat. Lincoln had reason to believe that Richardson started the rumor.

"I am not a Know Nothing. That is certain. How could I be? How can anyone who abhors the oppression of negroes, be in favor of degrading classes of white people?" an exasperated Lincoln wrote to Joshua Speed, with whom Lincoln had lived in Springfield and who now lived in Kentucky. "As a nation, we began by declaring that ‘all men are created equal.' We now practically read it ‘all men are created equal, except negroes.' When the Know Nothings get control, it will read ‘all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and Catholics."

As much as candidate Lincoln wanted to distance himself from the prejudices of the Know Nothing faction, he knew he would have to have it, as well as the immigrant vote. Prudently, he asked Jonas to keep the matter confidential. Jonas did.

Reg Ankrom is a former executive director of the historical society and a local historian. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources:

The American Presidency Project, "Election of 1856," at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/showelection.php?year=1856 .

Ankrom, Reg. "Wood's German heritage helped him rise to governor," Herald-Whig, July 12, 2015.

Brinkman, Michael K. Quincy Illinois, Immigrants from Munsterland Westphalia Germany, Vol. 1. Westminster, Maryland: Heritage Books, 2010.

"The Election," Quincy Whig, Nov. 8, 1852.

Jonas, Abraham to Abraham Lincoln, July 20, 1860, Library of Congress.

"To Joshua F. Speed, August 24, 1855," The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. 2, Roy P. Basler, Ed. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 1953.

To Abraham Jonas, July 21, 1860," Collected Works.

Powers, Rob. "Understanding Lincoln," at https://abrahamlincoln.quora.com/Close-Reading-1-Letter-to-Abraham-Jonas-July-21-1860 .

Reichley, A. James. The Life of the Parties: A History of American Political Parties. New York: Rowman Littlefield Publishing Co., 1992.

Tillson, John Jr. History of Quincy. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1905.