Experimental classes in Quincy changed education

During the late 19th century, schools in Quincy and across the country relied largely on memorization through repetition, with teachers using primers for rote instruction.

The Quincy Daily Whig of Feb. 5, 1880, reprinted a speech given in New York City by Francis Weyland Parker, one of the country's foremost educators, about this teaching method, which he himself practiced at that time, "When a child leaves school, if it doesn't love books and can repeat page after page by heart, the teaching has not been successful."

Corporal punishment--administered swiftly and often vehemently--usually accompanied this drilling into children's minds for failure to parrot back the teacher's words. By 1900, though, physically punishing pupils had mostly given way to a new method called "grading." At an educational conference in Quincy in 1901, Parker reflected on this change in his keynote speech: "In the old system flogging was a common method of punishment and nothing was pleasant. If anything was pleasant it was considered suspicious. If a word were dropped out so much flogging followed, and to avoid punishment was the object of the child. Then they (educators) changed the plan from punishment to bribery, as recorded by percentages, etc."

The next major change in formal schooling occurred in 1916 when John Dewey, the most influential educator of the first half of the 20th century, published "Democracy and Education." Schools now expected teachers to introduce a modicum of reasoning in their classes rather than have pupils merely mimic what they had said.

Dewey believed that only children older than 12 could reason abstractly and instruction too early in these skills would prove harmful. Some high schools gradually adopted these new classroom methods into their teaching, but repetition and memorization continued in lower grades.

Quincy Public Schools kept the rote instruction and rigid examination process it had begun in the 1870s into the second half of the 20th century. Class placement and entry into academic programs continued to be based on standardized tests and a pupil's ability to answer questions with only one "correct" response.

In the late 1960s, Quincy native the Rev. Phil Hoebing, a Franciscan priest and Quincy College philosophy professor of logic and ethics, became intrigued with the work of Matthew Lipman of Columbia University. Lipman, after working with his own children at home, had challenged these prevailing assumptions that reasoning cannot be taught to very young children and classrooms should only be places of drill.

Along with other philosophers, Hoebing enrolled in a 10-week summer seminar with Lipman at Columbia, and for five hours a day they discussed the practical applications of these innovative ideas about children and thinking. Seminar members noted that their college-age students were mostly ill-prepared to present logical arguments and could perhaps benefit from early instruction in reasoning.

Hoebing left the seminar with the tools he needed to outline a course in philosophical thinking for young children that would lead, he believed, to their being more rational and analytical long before they reached college.

After discussing his plan with other faculty members at Quincy College, he and Barbara Schleppenbach, a professor of English whose son was among the students, began teaching an eight-week course in 1973 at St. Anthony School in Quincy for fifth- and sixth-graders using Harry Stottlemeier's "Discovery," Lipman's text about logic. This was among the first experimental classes of philosophy for children in the United States.

The results startled observers: Following this course, the depth of questions students asked and their reasoning skills surged. Instead of not supporting answers or responding "Because I feel" or "I've been told...," students now gave reasons based on evidence, facts and the construction of a logical argument. Lipman's book, "Thinking in Education," later corroborated these and other anecdotal results with formal studies and empirical data.

As he continued to collaborate with Lipman, Hoebing began teaching similar courses in other Quincy elementary schools and speaking and holding workshops around the country about philosophy classes for children.

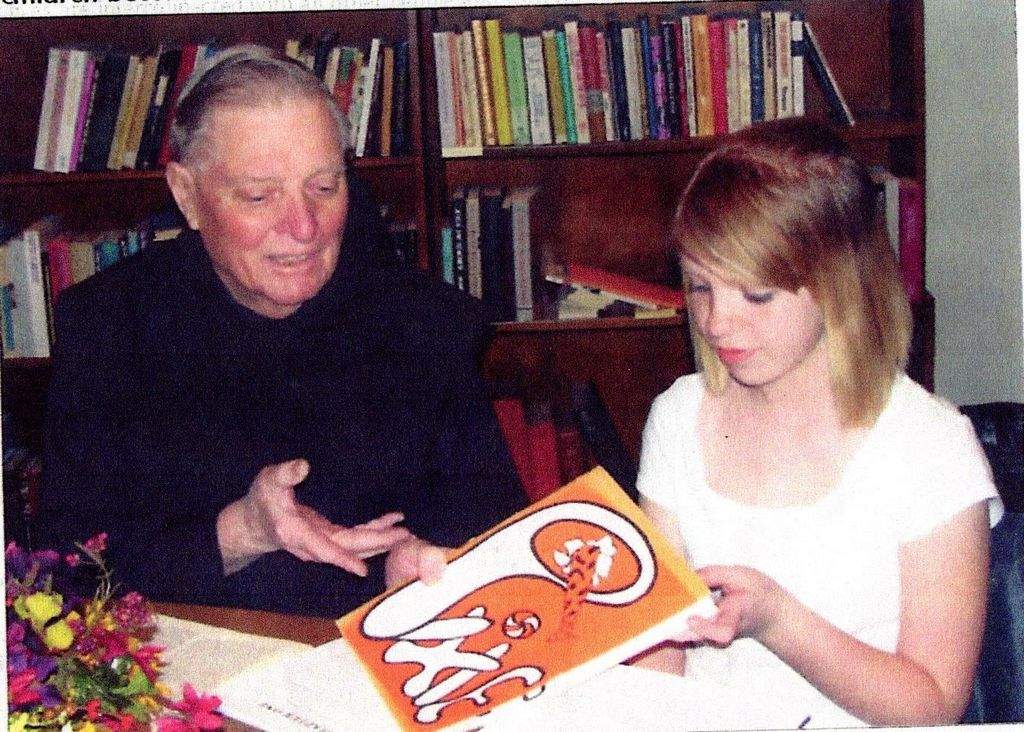

After seeing the initial success of classes in Quincy, Lipman, who later received an honorary doctorate from Quincy University, founded the Institute for the Advancement of Philosophy for Children at Montclair State University in 1974. In response to the pioneering programs of Hoebing based on the ideas of Lipman, a group of educators who realized the importance of teaching philosophy to young children founded the International Council for Philosophical Inquiry with Children and its journal "Thinking."

Hoebing's article for "Thinking" titled, "Pixie the Tree Hugger," introduced metaphysics--the study of being and reality--into the curriculum of these pioneering classes. In a Catholic Times interview and feature story about his work, he elaborated, "Children are naturally curious about the world around them and -- if given the chance -- will pose questions and explore aspects of life that most adults take for granted or assume. Children still look at the world with wonder and ask ‘Why do we exist?' and ‘What is really real?' "

Hoebing went on to establish College for Kids at Quincy College; it became the model for similar programs around the world, where trained instructors teach young children to think and reason with logic rather than feelings, hunches or, in many cases, haphazard thoughts. For two generations, he and other members of Lipman's seminars, instilled teachers with the skills to use philosophical inquiry and analysis in their classes. These innovative teaching programs can now be found in many colleges and universities in over 20 countries, where future educators learn to mentor children as young as kindergarten to think and reason logically.

These flagship classes in philosophy for children taught in Quincy played an important role in the increasing emphasis of educators on "critical thinking" and acknowledging that early instruction in these skills helps children move from drill to discovery and become more reasoning, rational and responsible adults.

Joseph Newkirk is a local writer and photographer whose work has been widely published as a contributor to literary magazines, as a correspondent for Catholic Times and for the past 23 years as a writer for the Library of Congress' Veterans History Project. He is a member of the reorganized Quincy Bicycle Club and has logged more than 10,000 miles on bicycles in his life.

Sources:

Dewey, John. "Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education." New York: MacMillan Co., 1916, pp. 152-63.

"Father Phil's Passion." Catholic Times, April 18, 2009, p. 24.

Lipman, Matthew. Harry Stottlemeier's Discovery. Upper Montclair, N.J.: Institute for the Advancement of Philosophy for Children, Montclair State College, 1977.

Lipman, Matthew. "Thinking in Education." Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991, pp. 131-41.

"Parker on Education," Quincy Daily Journal, Dec. 9, 1901, p. 2.

"Philosophy for Children." Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. plato.stanford.edu/" \h https://plato.stanford.edu>entries .

"Pixie the Tree Hugger." Thinking: the Journal of the International Council for Philosophical Inquiry with Children. June, 1987.

"Quincy School System: A Clear Exposition of Its Methods and Advantages." Quincy Daily Whig, Feb. 5, 1880, p. 2.