Protecting personal information a historical problem

In a time when privacy is an issue being hotly debated and defended through electronic media, we tend to forget how much some of our neighbors have always known about us.

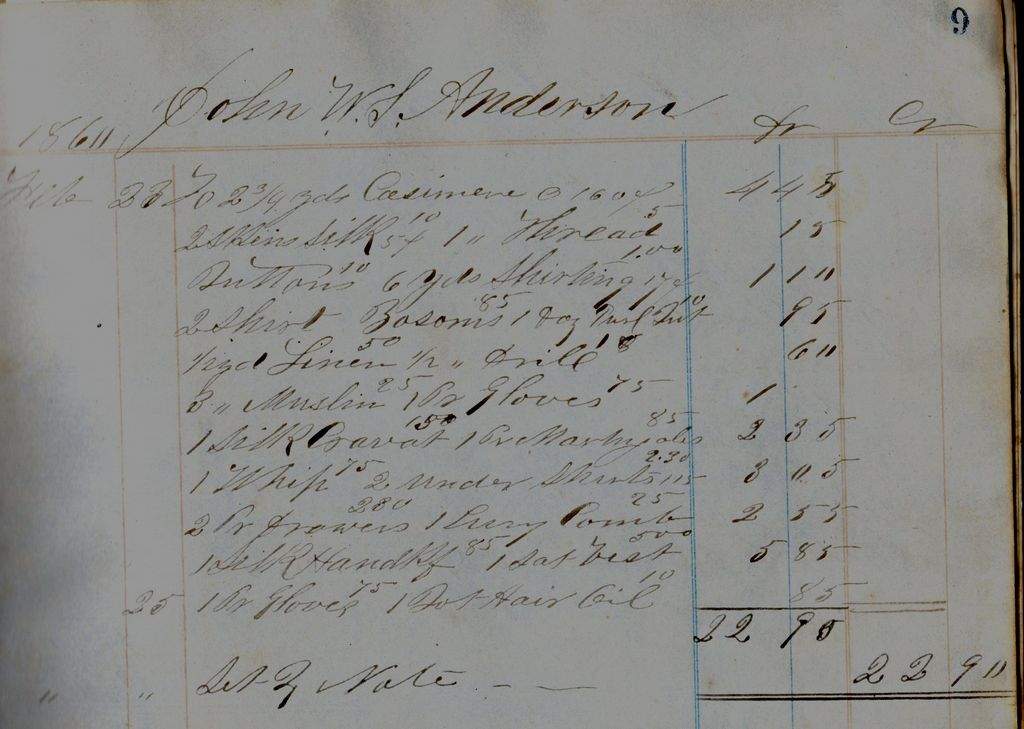

An 1860 ledger from a general store about 15 miles from Quincy, in a small town called Stone's Prairie, gives a window into Adams County country life just before the Civil War.

The ledger had customer's names written in vintage Spencerian calligraphy at the top of each page and recorded individual purchases and whether payments were made in cash or by trade or by note. This was a time when your name was your credit card, and payment was made a few times each year. The book itself serves as a kind of census of the community, for almost everyone occasionally purchased some goods they couldn't grow or hunt on the land. There are 639 pages in the ledger, some with more entries than others.

Thomas House, a distant cousin mine, purchased in September 1860 three yards of "corderogue" (corduroy) material at $1 per yard, which was quite expensive at that time. He also bought three bars of lead and 1 pound of powder, which came to a total of $3.71. He returned in January and paid his balance in cash. At that time House also replenished his stock of ammunition with more lead, a half-pound of tobacco and purchased a pair of boots, four steel pens and letter paper. He also bought four yards of pink calico and a skein of black thread, which he paid for at the time.

In March 1861, he returned and picked up an order for James House, for which $3 was added to his bill. He purchased for himself some fancy clothes: six yards of trouser material, a silk neck tie, a "lasting" vest, a "fine" shirt and one pair of summer pants.

In July 1861, the ledger says Thomas House owed the store $23.66, which was settled July 21 and the notation reads: "By order from Benj. House." A bill for $23 in 1860 money is equivalent to about $660 today.

Women's names are scarce in the ledger. Elizabeth Dempster is listed for one transaction. In May 1860 she purchased a pair of shoes for 65 cents, for which she traded eggs. Phoebe Lease bought a "fine" hat and one yard of ribbon for $2.50. Sarah Baker filled two entire pages with transactions acquiring materials, quilt backing, calico, buckram, a hat box and other supplies. She paid for some and traded pounds of butter and dozens of eggs for others.

Adams County itself purchased material from the store: four yards of "pant stuff," 10 yards of "bulk shirt stuff" and 12 yards of "print shirting." It was purchased "by order of H. Moreson and got by H. Lile" in September 1861. What was this material for? No notation was made.

Emily and Elizabeth Means each had a page in the ledger. They could have been local fashion leaders or perhaps even seamstresses, for in one purchase Elizabeth bought a "skirt skeleton," which was likely the boning for a hoop skirt, plus 10 yards of calico. She then returned the next day and purchased 10 yards of material. Emily paid her bill in cash. Elizabeth often purchased material on credit, which was paid for by her customers, or perhaps she created goods to be sold in the store. Elizabeth purchased mainly calico and canvas and muslin. The payments or credits to her account say things like, "By making 2 pr. pants .75" or "By work done for Mary Ann $1.00" or "By making two vests .75"

Emily, on the other hand, often purchased ribbons or shoes, and on one occasion left with a bottle of brandy, which cost $1.

Mr. Bracket Pottle, a wealthy land owner, had a certain status in the community to uphold. Among his purchases were for "Gloves by Lovejoy;" a "fine hat," a "shirt bosom and pearl buttons for seventy-five cents," a "Cassimere coat" that cost $6.25 plus other silks, a satin vest, a bottle of whiskey and one bottle of liniment.

In the cities merchants were able to rely on published credit ratings. The Western Credit and Safeguard Co. published a Merchants' Credit Guide for Quincy. The terms specify that the book remains the property of Western Credit and is only on loan to the merchant. There is a further statement that all information contained within it is confidential and should not be shared. It most definitely prohibited sharing the credit information with the person to whom it applied.

People were listed by last name in alphabetical order, along with their occupation, location and in the case of a woman, her marital status. Usually women were only listed if they were widows; otherwise the credit was tied to their husband's name.

In the right-hand column there was a number and a letter. The number was the number of responses for that name, and the letter indicated one of five classes of credit: V "Prompt pay and financially good"; N "prompt pay"; R "slow pay, financially good"; D "Slow pay, limited means"; "P "Cash on Delivery."

The sheet with this information says, "This Key must not be allowed in the possession of any person other than the Subscriber or his credit man, and should be kept in a safe and secret place." Some things never seem to change.

Beth Lane is the author of "Lies Told Under Oath," the story of the 1912 Pfanschmidt murders near Payson and is the former executive director of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

Sources:

Merchants Credit Guide of Quincy Illinois. The Western Credit and Safe-Guard Co., 1907.

Store Ledger (Stone Prairie General Store). 1861. Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.