Families paved pathway that led to slaves' freedom

Quincy's abolitionist network was in great danger after passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850.

Under federal law, slave owners could visit free states and retrieve their human property. By 1853, runaway slaves and free blacks living in Illinois could be fined and deported. It also was illegal for a slave owner to bring their slaves into the state for the purpose of freeing them.

Free blacks continued to move to Illinois. The dedicated abolitionists in Western Illinois were not deterred by the new laws. The elusive Underground Railroad became more organized and efficient, especially the path that began at John Van Doorn's riverfront sawmill.

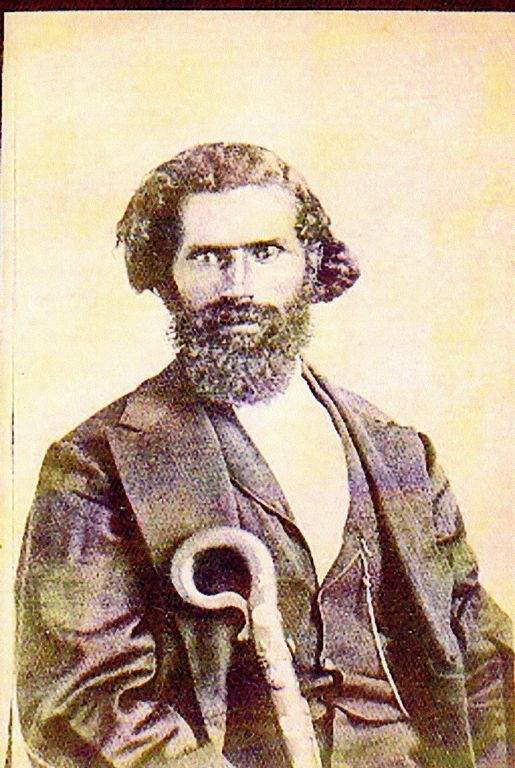

‘Free' Frank McWorter's town of New Philadelphia was affected by the new laws. McWorter and other former slaves lived in the town about 30 miles south of Quincy in Pike County. He and his family knew slavery personally. He had purchased wife Lucy's freedom in 1817, his own freedom in 1819, and later the freedoms of several other family members.

He worked as a free man in Kentucky before moving to Pike County in 1830. Juliet Walker, McWorter's biographer and great-great granddaughter, theorized that McWorter had other motives when founding the town. She wrote "his purpose in establishing New Philadelphia had been to provide a place of settlement not only for his family, but also for other blacks who might want to settle in Illinois."

McWorter died in 1854, followed by son Squire in 1855. Their deaths may have hastened the Clark family's move from New Philadelphia to Quincy.

Keziah (Cassia) Clark, daughter Louisa and three sons, Simeon, Monroe and William Clark, were in Quincy by 1855.

Keziah's eldest daughter, Louisa, had married McWorter's son Squire McWorter in 1843, and Squire had helped Louisa escape to Canada before Frank McWorter bought her freedom in Kentucky. She lived with her mother. Her brothers lived in the same Quincy neighborhood. Simeon and Monroe worked for John Van Doorn on the riverfront, laboring at his sawmill while secretly organizing passage to Canada for runaway slaves.

Simeon was an engineer and sawyer, Monroe was a blacksmithing laborer, and William worked for Sylvester Thayer's distillery next door. They all had homes on Third Street between State and Delaware.

The McWorter and Clark families' involvement with Quincy's antislavery crusade made this section of West-Central Illinois a well-organized Underground Railroad route.

Frank McWorter and his family knew the journey to Canada from Kentucky by the mid-1820s, as son Young Frank escaped to Canada when his master threatened to sell him. Frank's son Squire also knew the route to Canada well, and he helped his wife, Louisa Clark, escape there in the 1840s.

The McWorters' experience with the route was valuable for Quincy's network, which had scant communication with slaves it wanted to help.

On Leap Year Day 1860 The Quincy Herald accused John Van Doorn of encouraging people to cross the river to Missouri and entice slaves into leaving their owners, and once they were on the Illinois side of the river, help them flee north.

The country was dividing, and this was especially true in Wester Illinois, with slavery across the river in Missouri and threatening to spread to Kansas and beyond. The Herald reminded Van Doorn that his actions were illegal.

Clarissa Shipman of Pike County wrote to her family of "stirring times around here lately … half a dozen of our neighbors caught four fugitive slaves from Missouri and carried them back to their masters, for which it is said they got twelve hundred dollars. …There seems reason to believe that the fugitives are enticed to flee here. They come as far as Barry, as if they are among friends. There they were set upon and returned. I think we have fallen on evil times."

Another letter from Shipman reflected the growing tension in Adams and Pike counties: "There are secessionists in the neighborhood," she wrote. "One of them is C. Staats, who is a rabid one. It would go hard with us if he had his way. He has expressed his views fully, said he wanted to get a shot at a few of his abolitionist neighbors. It is said that he keeps three loaded guns by his bed. But Dr. Baker gave him to understand he was being watched and should any mischief occur he would fare hard. I think it frightened him."

Simeon Clark fought for the Union Army in the 38th U.S. Colored Infantry and then returned to Quincy for a few years before moving to Kansas.

In 1870, Clark and John Van Doorn united with other Quincy citizens who supported equality. The 15th Amendment had just passed, and a celebration was held among any Quincy citizens who honored freedom and had supported the antislavery stance before the Civil War.

The new amendment stated that the right to vote by citizens of the United States shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

Simeon Clark recalled his younger years as an Underground Railroad operator. He described "how he had, time and again, assisted his flying brothers from the pursuit of the negro-hunter and his bloodhounds. He drew a graphic picture of the condition of things then, and their now happy termination."

Just a few years before it was a federal crime to help people fleeing slavery.

The grand celebration was held April 16, 1870, with a procession beginning at the A.M.E. church. Over a thousand citizens of African ancestry, including some former slaves, marched to Pinkham Hall near Third and Maine streets. There Simeon Clark again addressed the crowd. Banners with portraits of Abraham Lincoln and then-President Ulysses S. Grant were in the foreground as music and prayer filled the afternoon.

The Whig covered the event and printed: "A few years ago such justice would not have been tolerated. Truly, the world moves. Light is breaking."

Heather Bangert is involved with several local history projects. She is a member of Friends of the Log Cabins, has given tours at Woodland Cemetery and John Wood Mansion, and is an archaeological field/lab technician.

Sources:

Cahill, Emmett. "Shipmans of East Hawaii," University of Hawaii Press, 1996.

"Council Proceedings." Quincy Daily Whig, Nov. 13, 1854.

"Grand Celebration of the Ratification of the 15th Amendment. Our Newborn Citizens in Council." Quincy Daily Whig, April 8, 1870.

Quincy city directories, 1855-1875.

Shackel, Paul A. "New Philadelphia: An Archeology of Race in the Heartland," University of California Press, 2010.

Walker, Juliet E.K., "Free Frank: A Black Pioneer on the Antebellum Frontier." University Press of Kentucky, 1982.