Quincyan's lifetime of service began in World War I

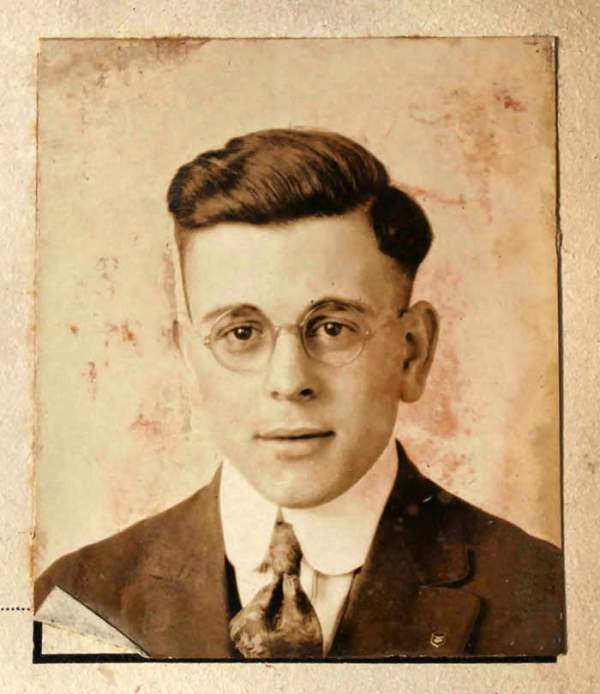

The Herald-Whig proclaimed: "Red Cross Leader, Harold W. Lewis, 66, Attorney, Dies Suddenly." Feeling ill, Lewis' wife was driving him to the hospital when he unexpectedly died. It was Monday evening, Jan. 6, 1964, when Quincy lost a devoted community servant and lifelong resident of the Gem City.

For more than 30 years, Lewis had been chairman of the Adams County Red Cross chapter. For more than four decades, he was a member of the Quincy Kiwanis club. And at times he held positions with the Boy and Girl Scouts, the Community Chest and the YWCA. He also was an active member of the American Legion, the Veterans of Foreign Wars and the Masonic Lodge.

Lewis' lifetime of service began when the United States entered the Great War in April 1917. He dropped out of college and joined the American Ambulance Field Service, an organization that attracted young volunteers, mainly college students.

The Field Service began in 1914 at the American Hospital in Paris but evolved into transporting wounded soldiers from the frontline to hospitals in the rear.

The Daily Journal on May 14 reported that "two Quincy boys, students at Beloit College, will go to France ... as members of the American ambulance corps. ..." Having passed the necessary examination, they were home raising money because volunteers were required to "pay for the transportation expenses (to Europe), uniforms, and other incidental expenses. ..."

The Ambulance Field Service promoted their volunteers to write home often. Family and friends were encouraged to submit the letters to the local news media. As a consequence, Lewis' observations appeared regularly in Quincy's newspapers.

With money raised, but minus his colleague who chose not to go, Lewis left for New York on June 6, where he received a short orientation and purchased a uniform patterned after those of the U.S. Army. Two weeks later Lewis telegraphed home: "Date of sailing changed for war reasons. Sail sometime today (June 20). Baggage on boat; report at ten. Leave during the afternoon on steamer Chicago."

The Daily Herald's July 5 edition noted that Lewis' mother had received a cablegram bringing "the welcome news" that her son had arrived safely in France and that he had gone directly to Paris, reporting to the American Hospital. After a perfunctory physical exam, he was sent to a training camp to learn "some French drills and their respective phrases. ..." He added, "I am a regular soldier now for I drink out of canteen and eat out of a mess-kit."

On July 25, after a short training period, followed by the receipt of a new Ford Model T, Lewis was sent to the front. He wrote on July 30, "In My Ford Ambulance, Somewhere in France." He then explained that his "work is hauling the wounded from the battlefield to the hospital. I wear a French large steel helmet, and have ready at hand my gas protector. These two things are very essential. We must always wear the heavy sickening helmet, and always carry the gas mask. Then too they have given me a ponderous gun to carry on my back or in my car."

Lewis was soon in the thick of the fighting, which he related in a letter to the folks in Quincy. "I have been in the great attack. You probably have read about it in the papers. I served the front line. For nine days, the French artillery bombarded the Germans and then the infantry moved on to their attack." The first trip was eye-opening. Lewis wrote that on "stepping out of my car ... and gathering the drivers together ... a shell whizzed over our heads and hit just sixty feet away. I saw it explode very plainly. We all ran for a dug out and for three hours the Germans bombarded us."

This was Lewis' baptism of fire, but the worst was to come. "Imagine how I felt when I saw a man being carried out of the next dugout ten feet away, with his head blown off. The shell ... went right through the bomb proof dugout." This was just the beginning. The Germans followed the bombardment with a gas attack.

Once the offensive began, the ambulance drivers worked, ate, slept and lived under constant shell fire. "I have seen trees fall, horses die and then I would have to run over them" while dodging huge shell holes, Lewis wrote his mother. But the worst was having a "shell strike ten feet away killing a man."

The only interlude in the constant shelling came when the Germans sent over gas. Unharmed by the shelling, Lewis was taken down by a few whiffs of gas and hospitalized for 10 days. The attack downed 15 out of 20 men in his section.

For the risk the American volunteers were taking, the French government insisted on reimbursing the men a token 5 cents a day, the equivalent to the pay of a French soldier.

In the fall of 1917, the U.S. Army absorbed the American Ambulance Field Service into the U.S. Army Ambulance Service. Lewis enlisted in the U.S. Army on Sept. 23, 1917; however, the only change was better pay. Instead of $1.50 a month he would receive $36. The men who joined the U.S. Army continued their service with the French.

Phil Reyburn is a retired field representative for the Social Security Administration. He wrote "Clear the Track: A History of the Eighty-ninth Illinois Volunteer Infantry, The Railroad Regiment" and co-edited " 'Jottings from Dixie:' The Civil War Dispatches of Sergeant Major Stephen F. Fleharty, U.S.A."

Sources:

The Archives of the American Field Service and AFS Intercultural Programs. the-afs-archive.org/index.php?option=com_2k&view=item&id=1645:1-1343-lewis-harold-wilcox<emid=230

"In the American Ambulance Field Service, 1916." eyewitnesstohistory.com/ambulanceservice.htm

McDonald, Chris. "Three Lying or Four Sitting," "From the Front in a Ford,?the WW I Letters of Kent Dunlap Hagler." Lincoln Land Community College Press: Springfield, Ill., 2015.

Stallings, Laurence. "The Doughboys, The Story of the AEF, 1917-1918." Harper & Row, Publishers: New York, 1963.

The Quincy Daily Herald, May 14, July 8, July 31, Aug. 31, Sept. 15, Nov. 8, Dec. 5, 1917; May 7, 1918; Jan. 28, May 5, 1919.

The Quincy Daily Journal, May 14, Nov. 5, Sept. 5, 1917; March 31, June 18, Aug. 8, 1918.

The Quincy Daily Whig, May 16, June 21, Aug. 5, Sept. 15, Oct. 20, 1917; May 8, July 11, 1918; Jan. 29, 1919.

The Quincy Herald-Whig, Jan. 7, 1964.

"The United States Army Medical Service Corps, World War I, The Ambulance Service." history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/HistoryoUSArmyMSC/chapter2.html