Farmer awarded Medal of Honor for role in battle

Joseph Wartick was unmarried and 24 years old when the Civil War broke out. He was born and grew up in Pennsylvania, but in 1854 the family came west to Illinois, settling in Camp Point Township. When the slavery issue led to secession with Lincoln's election and hostilities broke out in April 1861, young men like Joseph's brother John volunteered to put down the rebellion. Joseph waited, enlisting March 5, 1862. With the Illinois ranks filled, he crossed the river and joined a Missouri regiment.

Wartick's 6th Missouri Infantry was part of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Union army that landed on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River on April 30, 1863, and fought the rebels at Port Gibson, Champion Hill, and Big Black River in Mississippi.

By May 18, 1863, Grant's troops had forced the rebels back inside Vicksburg's defenses. Having trapped the Confederates, Grant saw a chance to finish the campaign. Therefore on May 19, thinking he could catch the rebel defenders unprepared, Grant's infantry assaulted their works. The attacked failed. Grant's men were driven back and suffered 1,000 casualties.

Having failed to penetrate Vicksburg's defenses, Grant spent two days studying the fortifications and planning a second attempt to capture the fortress-city and open the Mississippi River. Orders were issued on May 21 for a general assault on the rebel lines for the next day.

On notification of Grant's plan to again storm Vicksburg's fortifications, Gen. William T. Sherman prepared for the attack. Sherman's focus was the same as the failed attack, and that was to capture Stockade Redan, an earthen fort, protecting the northeastern approach to the city. First, Sherman moved his heavy artillery forward to bombard and soften up the rebel defenses. Next, a storming party of 150 volunteers was assembled.

It was certain from the moment the plan was put together that these men would draw a concentration of rebel fire, and few were expected to escape unscathed. Thus, they were quickly named and forever known as the "Forlorn Hope."

Stockade Redan was protected by a ditch approximately 8 feet wide and 6 feet deep, making an infantry assault almost impossible. Sherman concluded that the four-hour bombardment would give the storming party just enough time to run down the aptly name Graveyard Road, build a bridge, plant the scaling ladders, and the following brigade would capture the fort. To accomplish this hazardous task, the "Forlorn Hope" would have to carry the necessary bridging material while crossing a quarter-mile of open ground.

The senior officers knew those carrying the logs, planks and ladders were on a suicide mission, so only volunteers and single men would be accepted. To find the men, regiments were assigned a quota. When it came to the 6th Missouri Infantry, Adams County farmer Joseph Wartick was the first man to step forward.

Fifteen months after putting on a blue uniform, Private Wartick volunteered to do what most men saw as impossible and many foolish. Years afterward, a local newspaper reporter asked if he had been afraid when he volunteered. Wartick answered, "I don't know. I heard what my colonel said, believed it should be done and wanted to help do it." He then added, "It was pretty bad business. I don't know how I escaped death."

Wartick explained that "two men carried a log, or a plank or a scaling ladder." The men were divided into three groups. Those carrying the logs -- the groundwork of a bridge -- led. They were followed by the men bringing the planks to form the bridge. Last would be the scaling ladders.

Precisely at 10 a.m. the artillery stopped, and the storming party broke cover at a dead run. Wartick said the storming party was under fire all of the way, with half of the men killed or wounded before they reached the ditch. With their numbers depleted, "the men found it impossible to construct any sort of a bridge by which a charging column could cross the ditch."

Unable to retreat, the survivors had no choice but to jump into the ditch for cover. Now trapped, their situation worsened when the enemy lobbed short-fused artillery shells over the parapet. Some were thrown back before they exploded. Wartick chose to escape the primitive grenades, scrambled out of the ditch, up the enemy parapet, barely below the firing, but out of harm's way. He was alive but not unscathed. Wartick had "received six slight wounds and one serious one through the right lung."

In darkness, he made his way back to the Union line and was hospitalized. He made a full recovery and eventually returned to duty.

But with the failure of the second assault on Vicksburg's defenses, Grant's troops settled into a siege, which lasted until July 4, when the Confederates surrendered.

Two more years of fighting lay ahead for Wartick and the 6th Missouri. The regiment went on to see action at Missionary Ridge, the Atlanta Campaign, Sherman's March to the Sea and the Carolinas Campaign. With the war's end, Wartick went to Washington, D.C., and took part in the Grand Review. He was discharged May 27, 1865.

Returning to Adams County, Wartick returned to farming. He married in August 1866. In 1896, Wartick moved his family to Kansas, where he died April 7, 1910.

Like most Union veterans, the war was always part of his life. Many joined the local Grand Army of the Republic where they sometimes regaled comrades with old stories. But as time passed, some received long overdue recognition. This was the case for the survivors of the "Forlorn Hope."

For deeds of valor the government had one award -- the Medal of Honor. During the War of the Rebellion, Congress passed two resolutions providing Medals of Honor for distinguished gallantry in action. It was to be awarded to those men, who outside of the line of duty and beyond the order of superiors performed an act of conspicuous bravery.

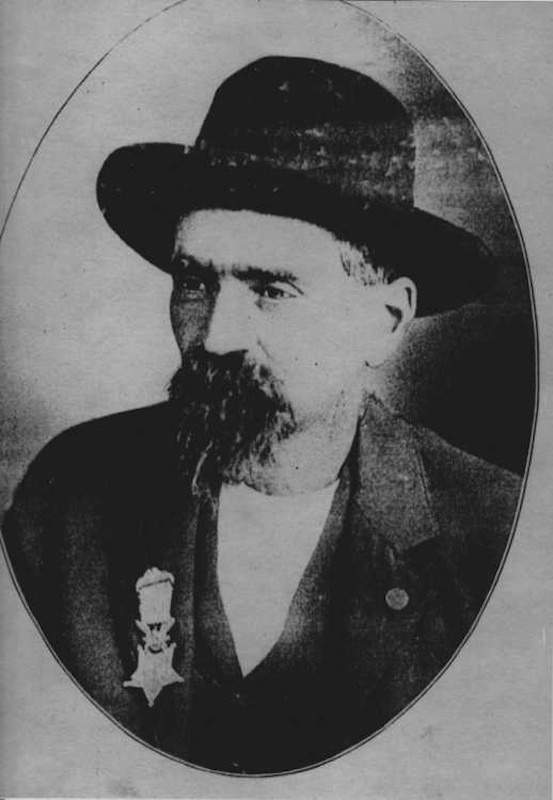

In 1894, 53 survivors of the "Forlorn Hope" were presented with Congressional Medals of Honor for their courage and willingness to attempt what proved to be impossible at Vicksburg on May 22, 1863. One of those recipients was Adams County farmer Joseph Wartick. He is a great-great uncle of Quincy physician Tim Jacobs.

Phil Reyburn is a retired field representative for the Social Security Administration. He wrote "Clear the Track: A History of the Eighty-ninth Illinois Volunteer Infantry, The Railroad Regiment" and co-edited " ‘Jottings from Dixie:' The Civil War Dispatches of Sergeant Major Stephen F. Fleharty, U.S.A."

Sources:

Ancestry, Joseph Wartick in the U.S., Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861-1865; Joseph Wartick, 1837-1910.

Beyer, W.F. and Keydel, O.F. Deeds of Valor: How America's Civil War Heroes Won the Congressional Medal of Honor. Stamford, Conn.: Longmeadow Press, 1992.

Dubray, Gail, Arma, Kan., provided copies of volunteer enlistment and current newspaper clippings.

Find A Grave Memorial, Private Joseph Wortick, Wartick (1837-1910).

Hicken, Victor Illinois in the Civil War. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1991.

The Walnut Valley Times (El Dorado, Kan.) Sept. 30, 1907, and April 15, 1910.

War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. 128 vols. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901. Series 1, Vol. 24 (Part II), pp. 264-265, 273-274.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/JosephWortick

andspeakingofwhich.blogspot.com/2012/forlorn-hope-at-vickburg.htm