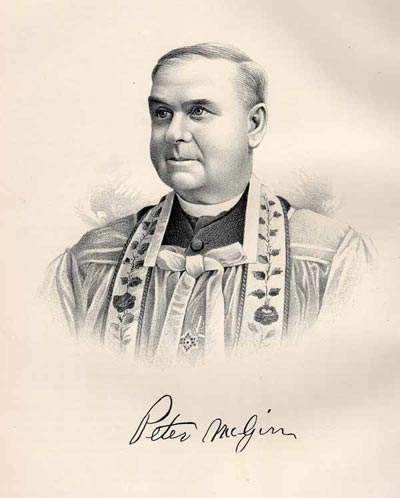

Father Peter McGirr: Patron of 'Father Gus'

The body of the Rev. Peter McGirr is buried in a small plot in Bloomfield Cemetery nine miles north of Quincy. Rising above the grave is a granite obelisk with a crowning crucifix. Its shadow each day marks Father McGirr’s resting place with the same sign of the cross with which he blessed his flock. It would be a quiet place but for the whispers of winds that race up the knoll and through the grass like giggling children who disappear in the descent on the other side.

There are few pilgrims these days to Father McGirr’s grave. But he chose his surroundings to be as close in death as he was in life to his several Irish relatives and friends in the cemetery he established. It was developed adjacent to St. Joseph Catholic Church, a mission church he founded in 1871 while pastor of St. Peter Catholic Church in Quincy. Names of Ireland are etched in the stones around him: Dempsey, Egan, Gunn, Hirty, Kelly, Kirk, McElroy, McGovern, McLaughlin, the brothers and sisters of McGirr and others.

For most who are buried on this emerald green hillside, life ended at the turn of the 19th century. The inscription carved into the priest’s monument indicates the tasks to which he devoted himself on earth ended in March 1893.

Father Peter McGirr might have entered eternity as most do, with collections of sorrows and joys — “long-suffering” or grace as a successor priest calls them — that life brings to all. But McGirr was a strong priest. It is his strength that history particularly remembers, his strength in a day of discrimination when he sheltered and encouraged one of the least of his flock in Quincy, a black youngster named John Augustine Tolton. McGirr led Tolton to his vocation, a calling in which he became the nation’s first African-American Catholic priest and that put him today on a journey to sainthood.

McGirr was born June 29, 1833, in County Tyrone, Ireland. He was the third boy in a close family of ardent Catholics, and his eight brothers and sisters held the red-headed, freckle-faced boy to high standards in school. The people of his village of Fintona, a village twice as old as the Catholic Church itself, believed it the destiny of Peter McGirr, who had been named for a saint, to be a priest.

McGirr’s family was among the nearly 1 million people that famine and disease drove from Ireland between 1845 and 1852. McGirr, 15, and two older brothers left first, arriving in New York City in 1848. McGirr was sent on to Holy Cross College in Worcester, Mass., and would continue graduate studies at a seminary in Montreal, Canada. His brothers stayed in New York City. In two years they had saved enough of their earnings to bring the rest of the McGirr family to America. They chose to move to Bloomfield, following several other Irish settlers into the thriving community northeast of Quincy. Like the others, the McGirr family became farmers.

Ordained a priest at Alton Cathedral in 1861, Father McGirr was assigned to Pittsfield. Within months he was appointed pastor of St. Lawrence O’Toole Church, which he soon would rename for his patron St. Peter. In Quincy he built a school, a new church and rectory, and the mission church and cemetery on 2.5 acres at Bloomfield.

Although McGirr had suffered privation in Ireland and separation from his family, he did not know suffering like the child to whom he served as patron. Augustine Tolton by circumstance alone had been born into a family of slaves in Ralls County, Mo. In an undated interview, the late Adams County historian Father Landry Genosky wrote that slave owners of the time “saw to their slaves’ salvations, even if they didn’t educate them or make it possible for them to be free.” Father Landry was a well-known professor at Quincy College who edited the massive People’s History of Quincy and Adams County.

Father Landry said it was traditional in the Stephen Elliott family, which owned the Tolton children and their mother Martha Jane, for the youngest girl in the family to instruct the slaves in their religion. The Elliotts were Catholic, and each of the Tolton children, Charles, John Augustine and Anne, were baptized in St. Peter Catholic Church in Brush Creek, Mo.

After Martha Tolton spirited her children from Missouri and slavery to freedom (Elliott family tradition is that they were given their freedom) in Quincy in 1860, she and her children joined other black Catholics in attending St. Boniface Church. The son Charles died of pneumonia in 1861. The Rev. Herman Schaeffermeyer enrolled Augustine in St. Boniface School for the three-month term in 1865. But insults and threats by parents to withdraw their children from the school led to Augustine’s departure, much to the dismay of Father Schaeffermeyer.

There was little welcome for the Tolton family when subsequently they began attending St. Peter, whose parish family had grown to 1,500 under Father McGirr’s pastorate. While building his parish, McGirr “did his best to break down the clannish, nationalistic attitude of his compatriots and welcomed non-Irish families to the parish,” wrote Sister Caroline Hemeseth in her biography of Tolton, “From Slave to Priest.” McGirr’s admonition that “Christ died for all” consoled his black parishioners and silenced others, Hemeseth wrote.

McGirr enrolled John Augustine in St. Peter School and employed him as a janitor. McGirr instructed Tolton, gave him his first Holy Communion and had him serve the church as an altar boy. Noting the piety in his young charge, McGirr asked Tolton if he wanted to become a priest. It launched John Augustine’s journey, a difficult one. But Tolton had known few easy ones.

McGirr was among several priests who sought to get John Augustine admitted to a seminary in the United States. Denied admission to all of them, Tolton enrolled at St. Francis Solanus College in Quincy in 1878. It was there he met the Rev. Michael Richardt, a Franciscan priest, with whom Father McGirr found the way to aid Tolton on his journey to become a priest.

McGirr and Richardt were successful in winning appointment for Tolton to the Propaganda in Rome, a missionary training center, and getting the Diocese of Alton to pay for it. In Rome on April 24, 1886, at the age of 34, Tolton was ordained a Catholic priest. Father McGirr led the thousands who greeted him on his return to Quincy on July 17.

Father Tolton said the 9 a.m. Mass at St. Boniface Church the next day. Father McGirr preached the sermon, a homily about a black child’s path to the priesthood.

Reg Ankrom is executive director of the Historical Society. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources

Bauer, Rev. Roy. "They Called Him Father Gus: The Life and Times of Augustine Tolton, First Black Priest in the U.S.A." Quincy, Illinois: St. Peter Parish.

"Bloomfield Cemetery." Handout provided during dedication of plaque at Bloomfield Cemetery July 24, 1977. MS9, Adams County--Mendon, Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County (HSQAC).

Brush Creek's Ebony Dream: Father Augustus Tolton, 1854-1897. Ewing, Missouri: Hall's Mill Farm, 1986.

"Father Augustus Tolton, 1854-1897." Office of the Cardinal, Archdiocese of Chicago, 2010. MS920, Tolton, Rev. Augustine, 1854-1897, HSQAC.

Frey, Mrs. Gerald. 1974 interview by the Rev. Landry Genosky, undated. MM27, HSQAC.

Hemeseth, Caroline. From Slave to Priest: A Biography of the Rev. Augustine Tolton (1854-1897), First Afro-American Priest of the United States. Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1973.

Zurbonsen, A. Clerical Bead Roll of the Diocese of Alton, Illinois. Quincy, Illinois: Jost & Kiefer Printing Co., 1918.