Tom Jasper steamboat a staple of mid-1800s life

From the founding of Quincy in 1822 by John Wood, the town grew tremendously. By the 1840 census, 2,300 people had braved the trip from the east to settle the Mississippi town on the edge of civilization. Most pioneers made the trip by a combination of steamboat passage and on trails like the Cumberland Road.

The census of 1850 recorded the community’s population had tripled to 6,900. This count showed Quincy was one of the largest settlements in the emerging west. In 1853, Congress made Quincy a port of entry for foreign goods, which made Quincy an important center for steamboat travel and distribution. By the end of the decade, arrivals to Quincy by steamboats had grown from less than 50 in the mid-1830s to nearly 3,000 by 1859. Quincy’s growth continued in the 1850s, resulting in the count for 1860 showing Quincy’s size again had almost doubled to 13,700 residents, making it the 69th largest city in the country.

At the beginning of the next decade, the Civil War would greatly consume the efforts of the town, slowing its growth. After the war, the city resumed its fast pace of development. By 1867, advocates for commerce were reaching out to bring business into the area. James Singleton had arranged to bring the state fair to Quincy in order to boost agriculture and its supporting industries. Samuel Holmes and others were building a railroad bridge across the Mississippi that would continue Quincy’s role as a crossroads center. Thomas Jasper and others would form the Saint Louis and Quincy Packet Co. to increase river traffic to the city. All this activity would lead to population growth of 75 percent at the next census.

Quincy, with 24,000 people in 1870, was the 55th largest city in America.

Of the three ventures, the new packet company was the most risky. Its founders would go up against John McCune and the Saint Louis and Keokuk Packet line. This company was the oldest packet company and McCune the most respected steamboat man on the river. To counter McCune, the owners of the new packet company introduced a new boat that was larger and fancier than any in the competing line. The new boat was named the Tom Jasper for the prominent Quincy investor, company officer, and former mayor.

The company sent its lead captain, Frank Burnett, to Madison, Ind., to supervise the construction of the new boat. Burnett arrived on April 9, 1867, and worked with the boat builders Vance and Armstrong, the company which built the hull and coordinated the specialty contractors responsible for the engine, fine carpentry and furnishings needed to complete the boat. The engine came from the large lower Mississippi steamboat Eclipse and was installed by Neal Manufacturing. The main cabin and the individual staterooms were constructed by John C. Crosley, marine architect. This firm was responsible for all the fine carpentry and decorative trim (gingerbread). The fine china, glassware and cutlery were provided by the G. P Mellen Co., which was also likely responsible for the lamps and ornate chandeliers that graced the rooms and main cabin of the boat. Two of these chandeliers are preserved today by the Historical Society with one on display in the Steamboat Room of the History Museum.

Newspapers all along the Ohio and Mississippi River announced the completion of the Tom Jasper in August. They reported that the stateroom walls were painted lilac. The doors were done in rosewood with oval panels containing artistic landscapes, figures, fruits and flowers. Local papers said the style of the boat was gothic, and the main cabin walls were pure white with gilded accents on the gingerbread.

The new boat finally arrived from the Ohio River on Aug. 16. On her first trip up the Mississippi from St. Louis, she attracted much attention. She was greeted by large crowds of people eager to view the conspicuous behemoth. At Clarksville, Mo., the Sentinel printed that everybody went to the wharf to view the magnificent steamer and that she appeared “like a thing of life.” When she reached the levee at Quincy, an anxious population, bolstered by martial music and booming cannon, greeted her arrival. Formal speeches took place at the landing, introducing the boat and crew to the city. City leaders gave the crew a stand of colors to fly on the boat. Jasper, the man for whom the boat was named, presented a splendid piano to be placed in the ladies cabin.

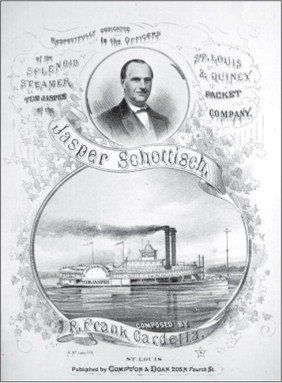

The piano, he said, was given so that the “youth may mingle in merry dance and songunder the guidance of woman.” To go along with the piano, a piece of music was published for the company by the St. Louis house of Compton and Doan. It was titled “Jasper Schottish” and carried images of the boat and Jasper on the cover. The Historical Society preserves in its files a copy of this sheet music.

The ceremonies continued on the boat as 500 people boarded for the trip to St. Louis. As soon as they were underway, dancing began and lasted until the arrival at St. Louis. At Hannibal, Louisiana and Clarksville, a number of people joined the excursion. The cuisine of the Jasper was reported as being magnificent and equal to food served at the best hotels. A string section performed for the diners in the main cabin. The boat arrived in St. Louis at 12:30 a.m.

This first voyage was a success. The new company had a grand, opulent boat that was the talk of the river system. Yet, the day to day competition between the St. Louis and Quincy Packet Co. and the Keokuk and St. Louis line proved more difficult. Later trips were much less successful. With all the new company’s spending for expensive furnishings, elaborate decorations and the $100,000 cost of building the large boat, the builders had neglected adequately sized boilers for the engine. The Jasper could not get up enough steam. The result was that the competing line’s boat beat them into port most of the time. The St. Louis and Quincy Packet assets were sold to the Northwestern Packet Line one year later. The Tom Jasper lasted until 1876, when it was remade with new boilers and renamed the Centennial.

The St. Louis and Quincy Packet was a loss for its investors, including Jasper. His loss would be made up by his efforts in distilling, banking and railroads. But like the other two endeavors — the attraction of the state fair to the city by Singleton and the construction of the railroad bridge across the Mississippi by Holmes — it brought business and people to Quincy. All three ventures involved great financial risk to their backers, and all three in a figurative sense, sent out ships. The people who came to Quincy to work on the three endeavors came because they were in search of a ship “to come in.” The three efforts helped Quincy become the 55th largest city in the United States and set the stage for 60 years of tremendous growth.

Dave Dulaney is a John Wood Community College employee and serves on the boards of the Historical Society and Midwest Riverboat Buffs Historical Club. He is a speaker, an author and a collector of memorabilia pertaining to local history and steamboats.

Sources

"Arrival of the New Steamer Tom Jasper." Quincy Herald, Aug. 17, 1867, p. 4.

"Arrival of the Tom Jasper." Louisiana Journal, Aug. 17, 1867, p. 3.

Barns, Janice. "Tom Jasper." In "River to Rail: The Rise and Fall of River and Rail Transportation in Madison Indiana." A digital history project by the Madison-Jefferson County Public Library and the Jefferson County Historical Society. www.mjcpl.org/rivertorail/boatstories/tom-jasper .

Edwards' Annual Directory to the City of Madison (Indiana). Edwards and Co. Publishers, 1867.

"Miscellaneous." St. Louis Democrat, Aug. 19, 1867, p. 4.

"Miscellaneous" and "River News." St. Louis Democrat, Aug. 14, 1867, p. 4.

"Opposition." Louisville Daily Courier, Aug. 21, 1867, p. 4.

"Quincy, Illinois." An article in Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quincy,_Illinois .

"River News." Louisiana Journal, July 27, 1867, p. 3.

"River News." Louisville Courier, Aug. 16, 1867, p. 4.

"River News." Madison Daily Courier, April 9, 1867.

"River News." Madison Daily Courier, Aug. 24, 1867, p. 4.

"River News." New Albany Ledger, July 25, 1867, p. 3.

"River News." St. Louis Democrat, Aug. 1, 1867, p. 4.

"River News." St. Louis Democrat, Aug. 15, 1867.

"River News." St. Louis Democrat, Aug. 15, 1867, p. 4.

"River News." St. Louis Democrat, Aug. 17, 1867, p. 4.

"River News." St. Louis Republican, Aug. 15, 1867, p. 3.

"River News." St. Louis Times, Aug. 18, 1867, p. 5.

"Table 9 Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1860." www.Census.gov/population/www/docummentation/twps0027/tab09.txt .

"Table 10. Population of the 100 largest Urban Places: 1870." www.census./population/www/documentation/twps0027/tab10.txt .

"The Contest in the Quincy Trade." New Albany Ledger, Aug. 20, 1867, p. 3.

"The Excursion to St. Louis on the New Steamer Tom Jasper." Quincy Herald, Aug. 22, 1867, p. 4.

"The New Steamer Tom Jasper." Aug. 22, 1867, p. 3.

"The St. Louis, Quincy and Keokuk Trade Competition Line." St. Louis Times, Aug. 15, 1867, p. 5.

"The Steamer Tom Jasper." Keokuk Daily Constitution, Aug. 20, 1867, p. 4.

"The Tom Jasper." Louisiana Journal, Aug. 24, 1867, p. 3.

"The Tom Jasper." Quincy Herald, July 23, 1867, p. 4.

"Tom Jasper." Clarksville Sentinel, Aug. 1, 1867, p. 3.

"Tom Jasper." Clarksville Sentinel, Aug. 22, 1867, p. 3.

"Various Items" and "Hotel Arrivals." St. Louis Times, Aug. 21, 1867, p. 5.

Way, Frederick Jr. Way's Packet Directory, 1848-1994. Athens: Ohio University