Sauk Village becomes Quincy

In exchange for a prized hog, Quincy founder John Wood settled a dispute with local Native Americans to solidify his foothold in the spring of 1823 in what would become the city of Quincy.

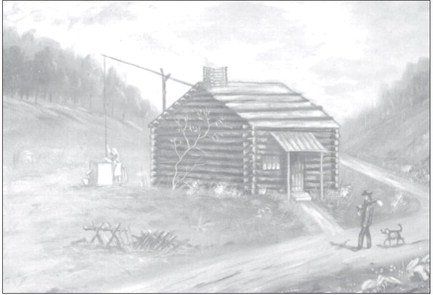

Wood had been camping since the summer of 1822 at what would later become Front and Delaware streets. The area was full of Native Americans, he noted, and only few European-American settlers. Wood soon began construction of a cabin and spent his first night in it on Dec. 9, 1822.

During the following spring, some of the Native Americans buried one of their own in a sitting position under a tree near Wood’s cabin. They had built up around the body a sort of tomb of wood, bark and sticks. Soon the odor of the decaying body became unpleasant. Wood and early settler Jeremiah Rose, who had moved in with Wood in March, set fire to the tomb, thus cremating the Native American’s remains. The Native Americans who had buried the person were insulted and confronted the settlers. As compensation, Wood and Rose gave the Native Americans a hog, which they then ate, thus appeasing them for the affront.

The cremation incident was not Wood’s only run-in with the local Native Americans. Later in 1823, Wood raised a crop of corn and pumpkins near his cabin. On one occasion Wood caught a Native American carrying off a load of pumpkins. Wood confronted the Native American and tried to explain that taking the pumpkins was wrong; however, Wood was unsuccessful in making his point clear. Wood relented, gave the Native Americans the pumpkins back and added a large watermelon to the lot. The Native American was pleased and tried to thank Wood with the Native American’s minimal grasp of the English language. He placed his hand gently on Wood’s shoulder and said, “You are a big rascal.” This was understood to be the Native American’s attempt to state that Wood was a good “Chemoka” man, meaning a good white man.

Ultimately, Quincy would become a friend to many dislocated peoples, including African Americans fleeing slavery in the South and Missouri, Mormons running from persecution in Missouri, and the Potawatomi tribes of Native Americans on the “Trail of Death” from northern Indiana through Quincy to Kansas. However, in the early 1800s, European-American settlers and Native Americans were still determining whether and how to co-exist on the frontier located in the Mississippi and Illinois river valleys. Quincy was no different.

French explorers Louis Joliet and Jacques Marquette had explored the Mississippi Valley in 1673 and probably had passed through the Quincy area around July 1. Trading between Europeans and Native Americans soon arose. A trading post called Bluffs existed here from about 1730 through 1813. Prior to and concurrently it had been a robust Native American village referred to as “Sauk Village” by European and American traders and settlers.

The site at Front and Delaware was the beginning of a Native American trail that led up the ravine to the top of the bluff, one of the few natural inclines from the Mississippi River to the top of bluff in Quincy. The trail then wound over toward State Street and east toward Payson and then Beverly. The Payson and Beverly prairies were buffalo hunting grounds. The trail continued east to the Illinois River.

On Nov. 3, 1804, five chiefs of the Sauk and Fox tribes signed a treaty in St. Louis, ceding to the United States the land between the Illinois, Mississippi, Fox and Wisconsin rivers. However, there was immediately great disagreement about the terms of the treaty, which effectively pushed the Sauk and Fox tribes either west of the Mississippi or north. Unrest among the tribes and between the tribes and European-American settlers continued.

In 1805, Gen. Zebulon Pike was sent by the federal government to explore the Mississippi Valley further and secure the United States’ interest in the valley. He preferred the location of what would become Warsaw instead of Quincy as a better strategic point for military purposes. In 1815 Fort Edwards was built at Warsaw.

During the War of 1812, the British and Americans fought each other for control of the Northwest Territory, which included the modern states of Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin and a portion of Minnesota — and other areas. The British sought allies among the many Native American tribes, including the Sauk and Fox tribes of Illinois.

In September 1813, U.S. Brigadier Gen. Benjamin Howard lead approximately 1,400 militia men on a raid from a fort east of Alton, north through western Illinois. The object was to neutralize any Native American support for the British and exert control over the area for the United States. During that campaign, Howard’s troops destroyed Sauk Village. The Bluffs trading post was abandoned but not destroyed.

Prior to Howard’s raid, many Native Americans in Sauk Village had fled either south to Cap au Gris near Hardin or north to Iowa or northern Illinois. Those who went south were largely supporters of the Americans. A portion of those who went north ultimately joined up with Black Hawk, a Native American warrior who later led them in a war with American settlers in Illinois. In 1832 Wood volunteered to fight with the Illinois militia against Black Hawk’s warriors, as did later President Abraham Lincoln.

Between the destruction of Sauk Village and abandonment of Bluffs in 1813, the Quincy area was a quiet backwater. However, it was a part of the land between the Illinois and Mississippi rivers in Illinois that became the Military Bounty Tract. Parcels in the tract were awarded thereafter to the veterans of the War of 1812 and spurred the European-American settling of what would be Quincy and Adams County.

Wood and early settler Willard Keyes met during the winter of 1819-20 and together sought a stake in the Military Bounty Tract. In 1820, they settled in what is now Pike County. Later in 1820 they ventured north to explore likely parcels for more permanent settlement and passed through “Indian Camp Point,” a popular Native American camp site. After the area was settled by European Americans, its name was changed to simply Camp Point.

Wood and Keyes were within 12 miles of Quincy during their 1820 trip but did not visit at that time. In 1821, they returned north and identified a 160-acre parcel owned by Peter Flinn (or Flynn) as an attractive location. In the summer of 1822, Wood purchased the parcel, which was located near the former site of Bluffs, a name still used at the time to refer to the area.

Wood, Keyes and Rose observed little of what had been Sauk Village or the Bluffs trading post other than some remnants of traders’ huts such as chimneys and fireplaces and the “Indian mounds” that pre-dated Sauk Village. Nevertheless, there were many Native Americans still living in the area.

Gen. John Tillson, Wood’s son-in-law, recorded the Native American reaction to the steamboat “Western Engineer” passing through the area in 1820 or 1821. The Native Americans called it a “smoke boat” or “fire canoe.” On the bow running from the keel was “the image of a huge serpent, painted black, its mouth red, and tongue the color of a live coal.” The steam escaped through the mouth of this image. The Native Americans reportedly thought the steam was the power of their “Great Spirit” and that a big snake carried the boat on its back.

The Black Hawk War in 1832 and the ongoing expansion of European-American settlements throughout Illinois, especially northern Illinois, during the 1820s and 1830s marked an end to large, independent Native American communities in Illinois. However, Native Americans continued to live in the state, including the Quincy area, and to interact with the European-American settlers.

Additional information regarding the Quincy area’s Native American heritage at the time of Quincy’s founding and much earlier periods is available from the library of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, the Illinois Room of the Quincy Public Library, the Native American collections of the Quincy Museum, and Indian Mounds Park in Quincy.

Hal Oakley is a lawyer with Schmiedeskamp, Robertson, Neu & Mitchell LLP and a civic volunteer. He has authored several legal articles and edited, compiled and/or contributed to books and articles on local history.

Sources

Asbury, Henry. Reminiscences of Quincy, Illinois. Quincy, IL: D. Wilcox & Sons, 1882.

Collins, William H. and Cicero F. Perry. Past and Present of the City of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1905.

Conover, Janet Gates. "Some Indian Facts from Adams County." Unpublished paper, 1984. In HSQAC Research File: MsI Indians – Adams County.

"How We Celebrated: Unveiling of the Statue of the Late Gov. Wood on the Fourth." The Quincy Weekly Whig. July 12, 1883: 2, col. 1-6.

Stout, David B., Erminie Wheeler-Voegolin, and Emily J. Blasingham. Sac, Fox and Iowa Indians II: Indians of E. Missouri, W. Illinois, and S. Wisconsin, From the Proto-Historic Period to 1804. American Indian Ethnohistory. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1974.

Temple, Wayne C. Indian Villages of the Illinois Country: Historic Tribes. State of Illinois: Illinois State Museum, 1958.

Tillson, Gen. John. History of Quincy. In Past and Present of the City of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois