Feather dealer was tireless Quincy booster

Harris Swimmer and his wife, Lena Salomon, members of Congregation B’nai Sholom of Quincy, were a like-minded couple who used their acumen to serve the public interest and to advocate for many of the civic improvements now taken for granted.

Born in Colmar, Prussia (now Chodziez, Poland) in1844, Harris Schwimmer (subsequently Swimmer) came to the United States as a toddler with his parents, Isaac and Rosa Schwimmer.

After living in New York City until the mid-1850s, the family briefly lived in St. Louis, before moving to Quincy in 1856. Isaac opened a secondhand clothing store while Harry worked in the clothing store of Moses Jacobs, another immigrant from Colmar.

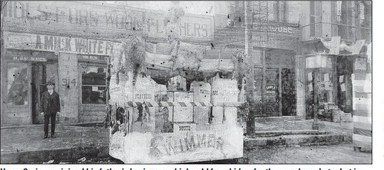

When the Civil War broke out, Harry, then 17, joined the Adams County-based Company E. Fiftieth Illinois Regiment, the “Blind Half Hundred.” By 1862, his father had begun to sell furs, hides, feathers and wool at 67 Hampshire (now 313 Hampshire), and Harry joined the business.

His wife’s sister, Amelia Ullman, was married to the founder of a huge fur business with offices in New York and Leipzig, Germany. Feathers were highly sought, and it was said that Swimmer eventually became “the largest dealer in feathers in this country.”

Swimmer, a self-made man, became deeply committed to civic improvements and probably realized that politics provided the best venue for accomplishing them. He started as a volunteer fireman, but moved to police work in 1874.

Perhaps walking the beat of the Second Ward made him a trustworthy figure to its residents. They, in turn, elected him alderman in 1878, returning him to that office off and on for the next 16 years. Swimmer was a strong Democrat, and his store was “a mecca to which all office-seekers journeyed….” Mentioned as a candidate for mayor in 1883, he rejected the idea, saying, “Every man who ever accepted the office left it much poorer than he was when he entered it.”

However, two years later he declared his candidacy for mayor. He was well known and respected for his business acumen, and in blunt language, he stated that Quincy could attract new businesses only by reducing taxes and investing in infrastructure. He pledged $100,000 [$2,439,000 in current dollars] of his own money to refinance city debt at a lower rate.

As the Democratic Party primary approached, the issue of religion seeped into the race. The Quincy Daily Journal, a Democratic paper, editorialized: “We say it would be a shame and an outrage to beat Parkhurst because he is a Protestant; a shame and outrage to beat Farrell because he is a Catholic; and a shame and an outrage to beat Harry Swimmer because he is a Jew. We say that it is a cruel shame to down any man on account of his religion; and we most devoutly hope that this will not be done in Quincy.”

In the four-person race, Swimmer ran second, receiving about half the votes of the winner. The Journal said, “Swimmer was surely punished because he was a Jew. The race question cuts a mighty figure yet in American politics.”

This defeat did not stifle Swimmer’s enthusiasm for Quincy. He would use his political skills whenever necessary. Quincy merchants could not agree on a fall festival in 1890. Swimmer suggested a two-day celebration that could draw 50,000 people.

By providing lots of entertainment, with appearances by the state’s leading politicians, everyone would benefit. He opined that party affiliation had no place in drawing customers: “What difference does it make if we bring the crowd? Democratic dollars sound just as well as Republican dollars as they drop into the till.”

Swimmer’s civic participation extended to service on the Board of Education for eight years and the Quincy Parks and Boulevard Association. A strong advocate to provide relief to the poor, he was one of the incorporators of the Quincy Humane Society in 1880.

Swimmer also had a deep concern about the safety and security of Quincy’s citizens on matters from controlling stray dogs to paying the city’s bills.

As alderman, he introduced the measure to have dogs licensed, and he led the effort to keep the water running and gaslights lit when the city could not pay its bills.

In 1871 he joined the local B’nai B’rith Lodge and became president of District Six, comprising Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota and Wisconsin. He was a trustee of a Jewish orphanage in Cleveland. Ever mindful of the opportunity to promote Quincy, at the 1905 District Convention, the three delegates from Quincy, Swimmer, Moses Kingsbaker and B.G. Vasen, lobbied for the new B’nai B’rith home for the aged to be located in their city. No doubt they were thinking about the boost it would create for Quincy by drawing visitors and creating jobs.

Swimmer also was grand foreman of the Ancient Order of United Workmen, a member of the Masons and at least five other fraternal organizations. These memberships and the offices he held in them allowed him to establish numerous connections at the state and national level. With a resume like this, it is no wonder that President Benjamin Harrison appointed him a deputy U.S. marshal in 1890, a position he held until his death in 1906.

Swimmer’s sudden death brought telegrams from Germany and all parts of the United States.

At the funeral, conducted after Masonic rites, a representative from each of the numerous organizations in which he was a member was a pallbearer.

The newspaper spoke of him as always being concerned with the public good, even if that meant taking an opposing view, whether it was supporting a tax levy to pave the streets or keeping the costs of textbooks low.

The paper stated: “He made himself useful to the community he served so long and that faithfully mourns, and mourns sincerely, at his bier.”

David Frolick is a Quincy native who obtained most of his education here. After receiving a doctorate from American University, he taught political science at North Central College for 36 years, retiring in 2007. He now lives in Columbus, Ohio, and continues his research on the history of life in Quincy.