Free Frank and David Nelson in Kentucky and Illinois

Abolitionists were organizing across the country as soon as a territory became a state in the United States. Some antislavery Americans met at lectures or rallies, and some serendipitously crossed paths as they traveled west to the new states in the expanding nation.

Free Frank (later McWorter) purchased his freedom in 1819, and lived in Kentucky for over a decade before moving to Pike County Illinois. His time as a free man amidst a dominant slave culture on the Pennyroyal plateau frontier of western Kentucky was spent earning as much money as possible to purchase his family members and prepare for a new start in the free state of Illinois.

While saving money to liberate himself and his wife, Lucy, Free Frank mined for saltpeter in the plateau area’s plentiful caves. He developed a profitable saltpeter business and in the 1820’s expanded it to Danville, Kentucky, about 40 miles from his farm in Pulaski County. Danville was a hub of activity and commerce where many pioneers stopped to restock their supplies before continuing westward. In the 1820’s Free Frank also purchased farmland from wealthy Kentucky politicians and landowners for future speculation. He was in contact with many prominent citizens while in Danville.

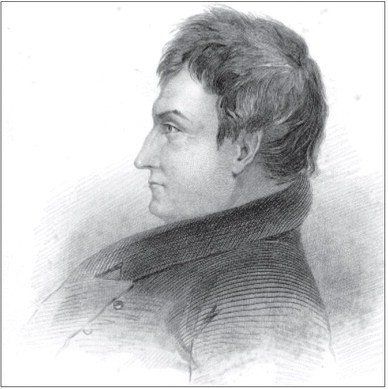

Originally from Tennessee, Dr. David Nelson arrived in Danville in 1827, having previously lived there while studying medicine. After his brother Rev. Samuel K. Nelson’s death in 1828, he replaced his brother as minister of Danville’s Presbyterian Church. From 1827-1830, Nelson was also on the board of trustees at Centre College, founded by Presbyterians in 1819 in Danville. His anti-slavery stance grew during this period and he soon made plans to move to Marion County, Missouri.

Free Frank traded his saltpeter business for his son Young Frank’s freedom in 1829. He then sold his farm and purchased Pike County, Illinois land. He made plans to leave Kentucky for Illinois in the fall of 1830. Some sources claim David Nelson also left in the fall of 1830, but no documentary evidence of this move has been uncovered. However, their locations continued to synchronize after they left Kentucky.

Nelson spent the next few years in Missouri preaching, and denouncing slavery. In 1831, he established Marion College in Philadelphia, Missouri as a Presbyterian preparatory college. He later met radical abolitionist Theodore Weld in St. Louis in 1835 and became more openly abolitionist. In late May of 1836 Nelson was chased from Missouri to Quincy by proslavery forces. After making it to Quincy he hid at fellow abolitionist Rufus Brown’s hotel at 4th and Maine Streets before the slavers confronted him. He was rescued by John Wood and a team of thirty abolitionists. The rowdy pro-slavery forces returned across the river to Missouri. Later that same year, Nelson established the Mission Institute east of Quincy, near present day Maine and 24th Street.

During this same period, Free Frank and his family were establishing their farm in Pike County, Illinois. In 1835 Free Frank purchased one hundred acres of Pike County land at Quincy’s federal land office on the north side of the square (now Washington Park). He and his sons Squire and Commodore returned to buy more acres in May and June of 1836. New Philadelphia was officially platted in September of 1836, and by that time, Free Frank McWorter owned 600 acres of land.

New Philadelphia, which was about 30 miles south of Quincy, was organized as a town and divided into 144 lots. Free Frank needed legal protection to secure his land and town. Pike County farmer and surveyor Reuben Shipman signed the plat book for the new village. He was a neighbor of Free Frank’s in Hadley Township, and his son William Shipman became a student at David Nelson’s Mission Institute in Quincy.

Fellow student Jane Stobie was from a family of abolitionists in Quincy, and she and William Shipman later married in Quincy before voyaging to the future state of Hawaii as missionaries. It was not unusual for students from the Mission Institute to marry and became missionaries. Many went to Canada to help escaping slaves. Free Frank and his family had known the route to Canada from Kentucky since at least the 1820’s and the family’s oral history acknowledges they were helping fugitives while in Illinois.

Free Frank’s first free-born child Squire McWorter helped his wife Louisa Clark escape from Kentucky to Canada in the early 1840’s. Their son Squire, Jr. was born in Chatham, Ontario in 1846 where Elias and Elizabeth Kirkland, former Mission Institute students taught at the British American Institute and helped escaping slaves.

In the 1850’s, after both David Nelson and Frank McWorter’s deaths, a verifiable antislavery connection between New Philadelphia and Quincy became known. The Clark family from New Philadelphia moved to Quincy in the 1850s and worked for the seasoned abolitionist and sawmill owner John Van Doorn. Jane Stobie Shipman’s brother and fellow abolitionist Alex Stobie also worked for Van Doorn.

Because teamwork and communication were key to the success of the ant-slavery Underground Railroad movement the possible early meetings between David Nelson and Free Frank McWorter are intriguing, and perhaps their early associations led to a more organized abolitionist network in western Illinois.

Underground Railroad activities in the Eastern U.S. are widely chronicled and memorialized. The fugitive slave stories of Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, William Still and others have been extensively researched told and re-told. As more forgotten documents are discovered and shared, the contributions of more local heroes such as Dr. David Nelson and Frank McWorter will be recognized and honored.

Sources

Ankrom, Reg. “Rev. Nelson and Abolition Come To Quincy”. Quincy Herald Whig, Dec. 23, 2012.

Asbury, Henry. Reminiscences of Quincy, Illinois. Quincy IL: D. Wilcox & Sons, 1882.

Bangert, Heather. “Black Abolitionist Network Grew With City”. Quincy Herald Whig , Jan. 11, 2015.

Bangert, Heather. “Families Paved Pathway That Led to Slaves’ Freedom”, Quincy Herald Whig , Sept. 18, 2018.

Cahill, Emmett. Shipmans of East Hawaii. University of Hawaii Press, 1996.

Centre College Special Collections, Digital Archives, Centre College Board of Trustees Minutes (vol. 2- 1828). https://sc.centre.edu/sc/minutes/bt2_1828.html

Deters, Ruth. The

Underground Railroad Ran Through My House!.

Eleven Oaks Publishing, 2008.

Quincy City Directories 1855-1875.

Ripley, Peter C., ed. The Black Abolitionist Papers , Chapel Hill NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1985.

Shackel, Paul A. New Philadelphia: An Archeology of Race in the Heartland . Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 2010.

Walker, Juliet E.K., Free Frank: A Black Pioneer on the Antebellum Frontier . Lexington KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1982.